Honouring ISSEY MIYAKE

The Legacy Remains: Merging Art & Fashion, East & West, Tradition & Technical Innovation

Continue with joy and an endless curiosity for the world, just like Issey-san did.

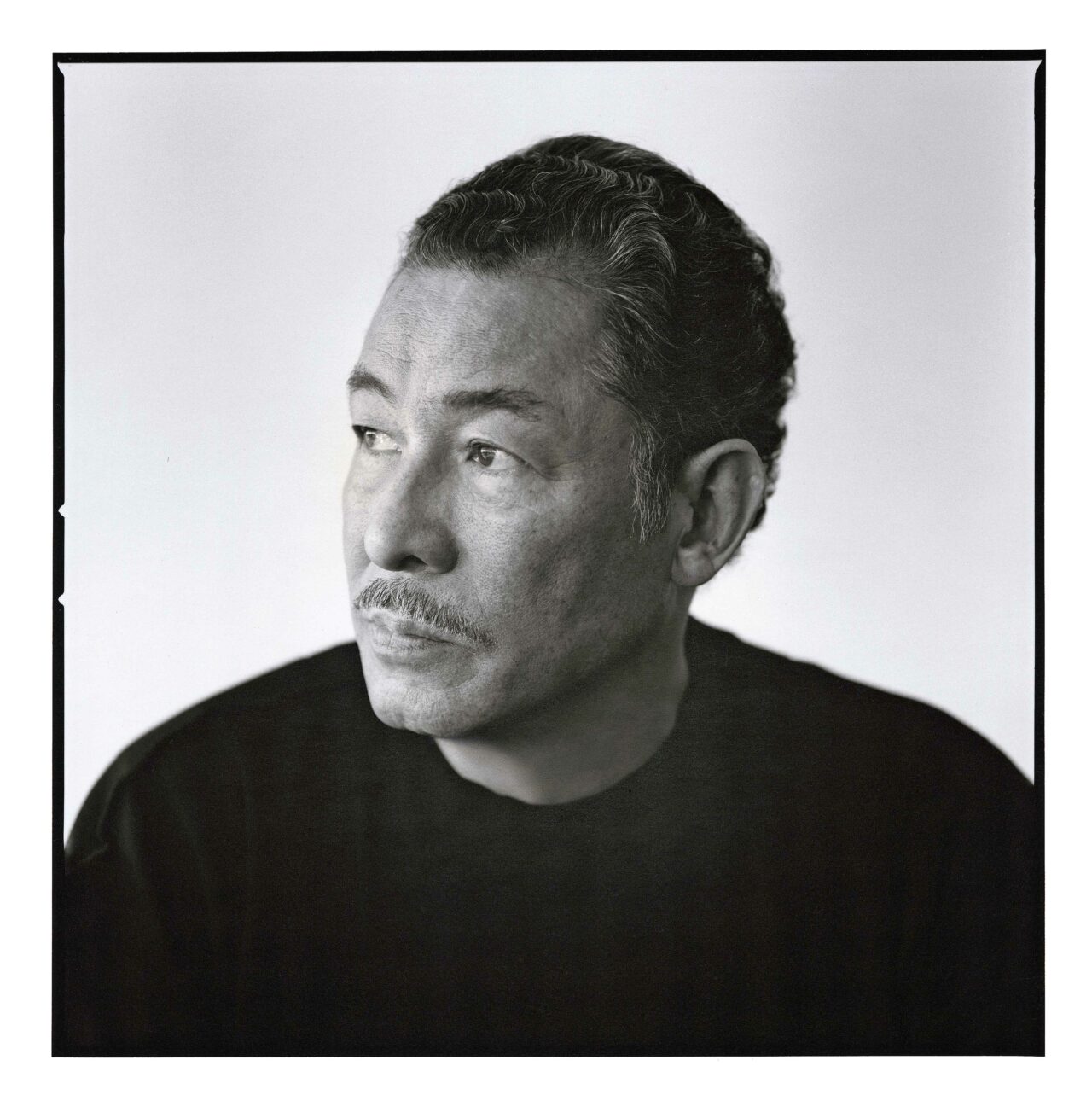

Issey Miyake, the renowned designer and founder of ISSEY MIYAKE and MIYAKE DESIGN STUDIO has passed away at age 84, leaving behind an extensive legacy that surpassed any boundaries of fashion, culture and trends, and one that will undoubtedly continue to influence generations to come.

Perhaps the entire ethos of Miyake can be best encompassed in his own words:

“Design is not for philosophy—it’s for life.” (1)

To say he was a visionary in this world would be an understatement. Miyake changed the way we wear our clothes and the potential of their production, transforming the humble cloth into a revolutionary art form embedded with practicality and utility that would modestly masquerade as an exceptional piece of product design. Valuing both traditional craftsmanship and technological advances at the forefront of design, his balancing act of the two was what made his work so genuinely visionary for contemporary daily wear. “I’m fascinated by all fields of design,” Miyake said. “Design as an approach to society, people, life. Even if it looks like what I have done has become fashionable, fashion to me is like the wind, I like to stay constant. I put my mind to making a product that people enjoy.”(2)

Miyake created clothes, uninterested in ‘fashion’ or trends..’ These were clothes for everyone. One could say that Miyake’s ethos was embedded in spreading joy through the medium of design. Having survived the atomic bomb in Hiroshima at a young age, this would perhaps shape his ethos, noting he preferred “to think of things that can be created, not destroyed, and that bring beauty and joy. I gravitated toward the field of clothing design, partly because it is a creative format that is modern and optimistic.” (3)

His outlook was global and undefined to his home country of Japan. As he mentioned at the press conference of his retrospective in Tokyo at the National Art Center in 2016, Miyake didn’t want to be viewed as a “Japanese designer” but rather a designer of the world, as his human-based and borderless approach to design led him to find inspiration in all techniques and cultures from the globe.

Miyake viewed clothing as universal. From designing the staff uniforms for Japanese electronics company SONY, to gifting Steve Jobs’ now iconic unofficial uniform of ISSEY MIYAKE black turtleneck sweaters. From architect Zaha Hadid to model and artist Grace Jones, many found their own unique and personal connection to his clothes.

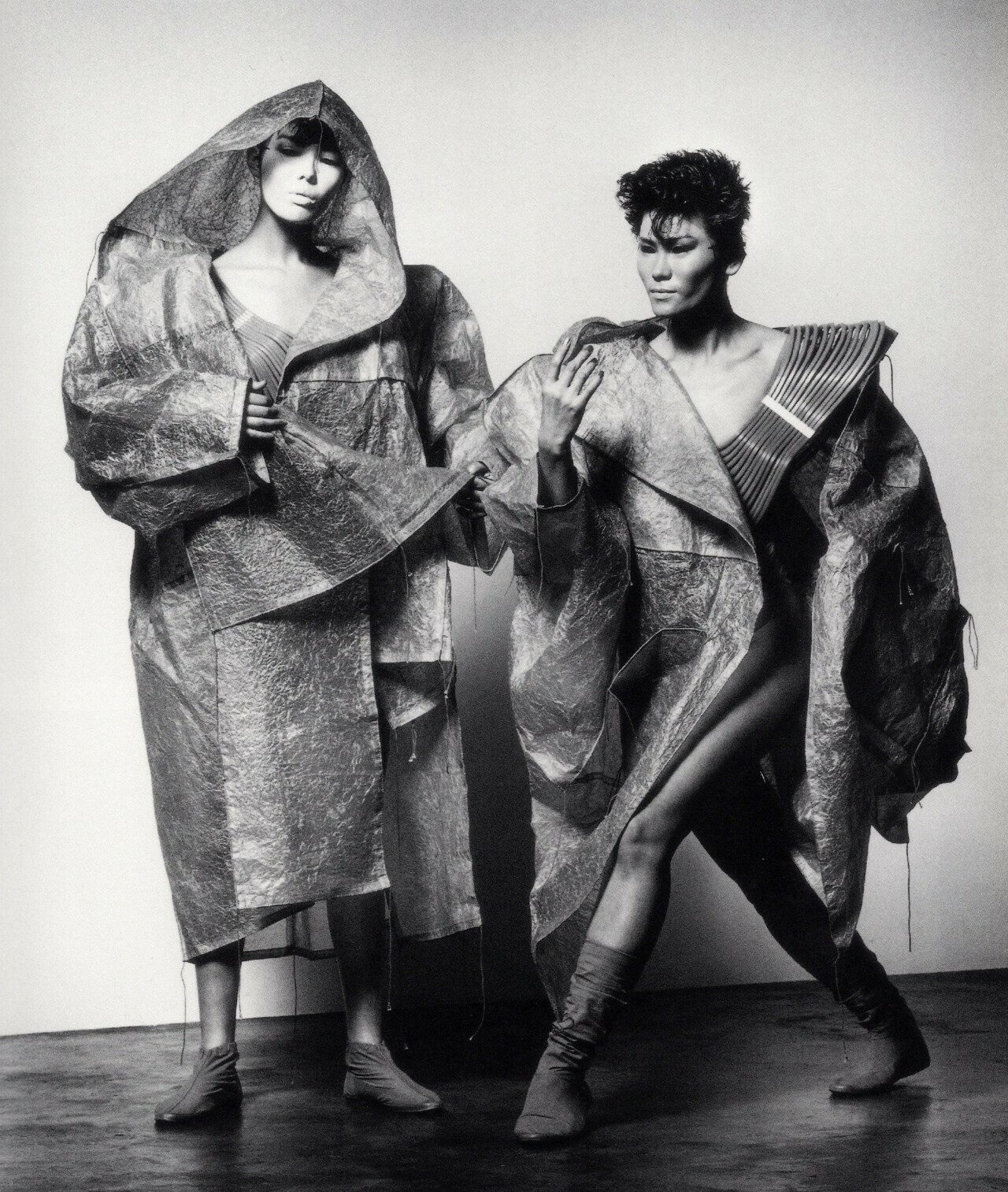

For Miyake, his north star was led by mono-zukuri — the Japanese term of making things — that placed emphasis on the development of his own materials and production. As a designer he respected the depth of traditional craftsmanship, yet equally led with an approach to merge innovation and the ‘newest technology through research and development’. Exploring the vast capacity of materials, form and silhouette. One of the earliest members of his team was textile specialist Makiko Minagawa, who would lead the exploration and development of fabrics that she still continues to oversee to this day.

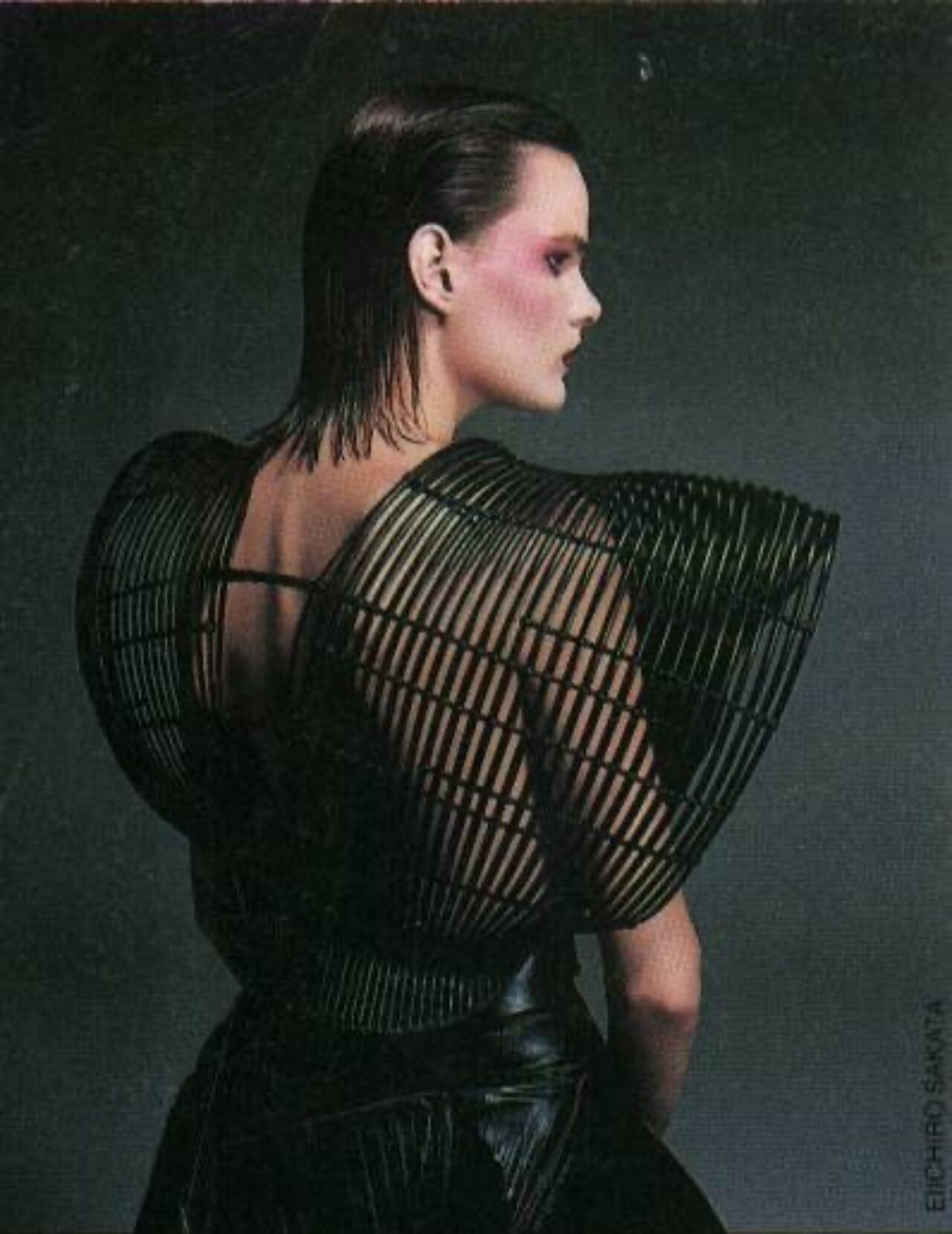

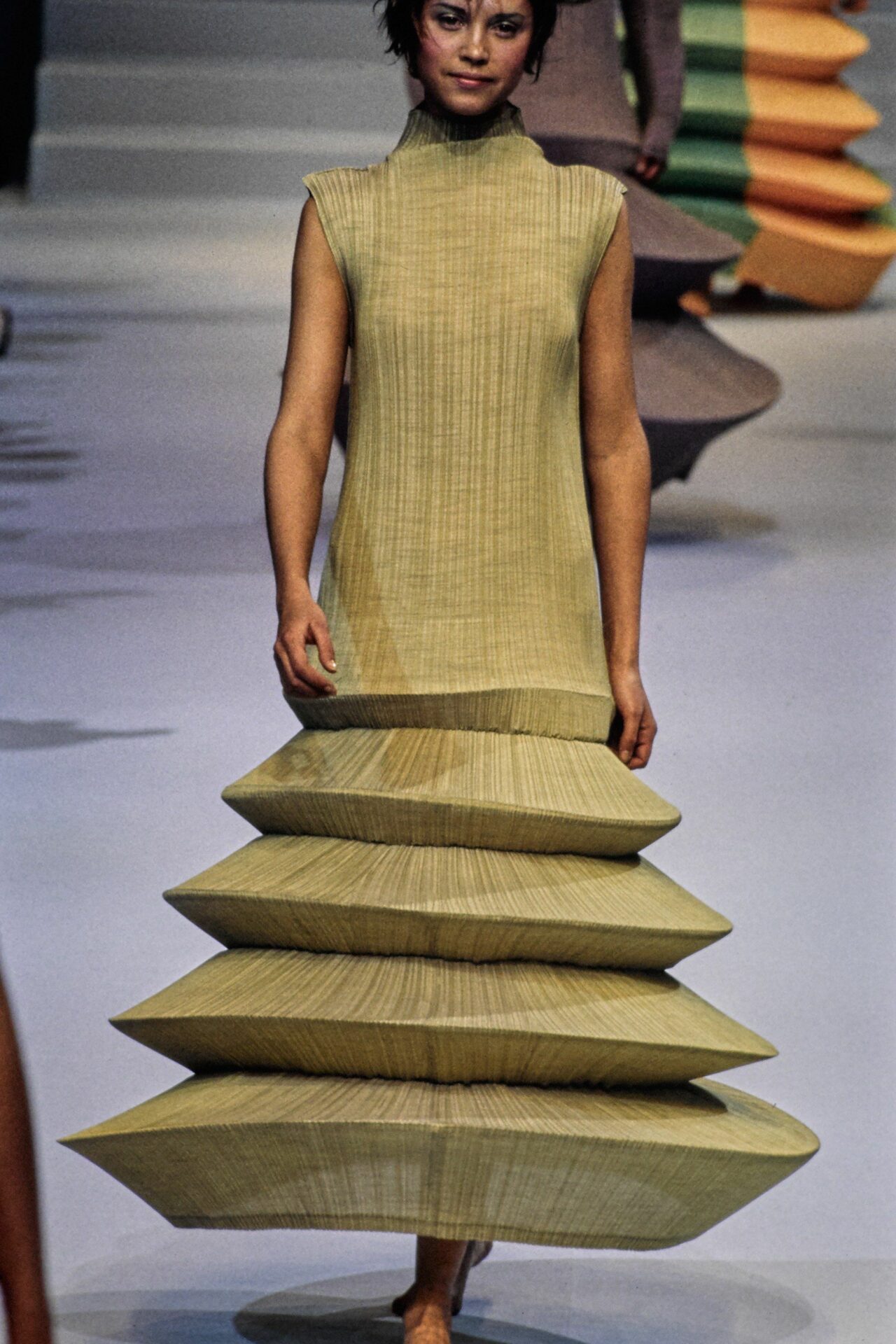

Miyake’s Plastic Body, the first in the Body Series in 1980 — a stoic, molded bodice formed from glass fibres infused with polyester resin — fused materials together for clothing that was completely unseen at the time. Or Rattan Body, a structural vest made from rattan and bamboo by craftsman Shochikudo Kosuge with help from artist Emi Fukuzawa for the Spring/Summer 1982 Collection. The piece was so impressive that it featured on the cover of Artforum, with the magazine’s editors at the time Germano Celant and Ingrid Sischy describing the work as ‘an icon of modernism, an intersection between past and future, East and West, rigidity and flexibility, nature and artifice.’

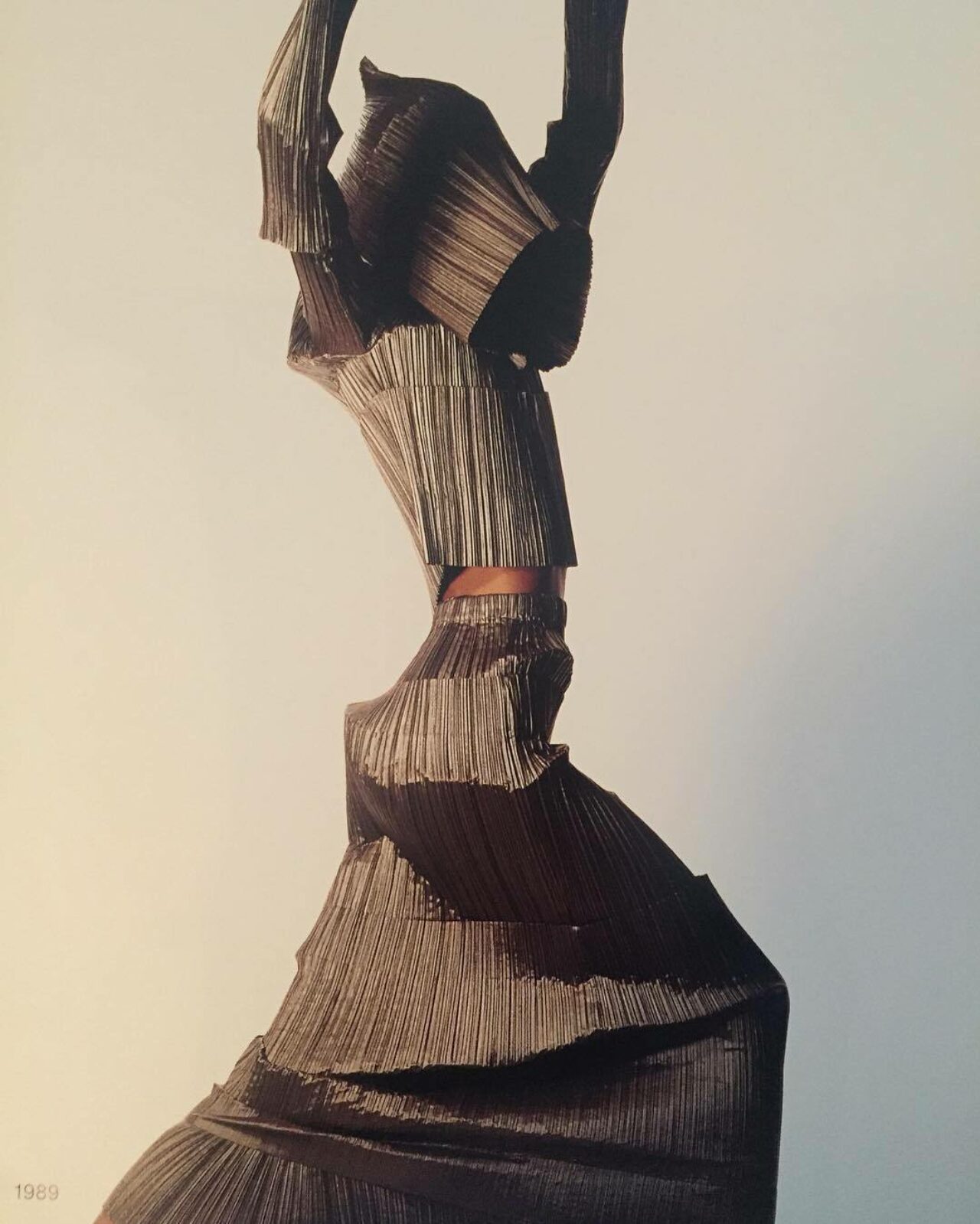

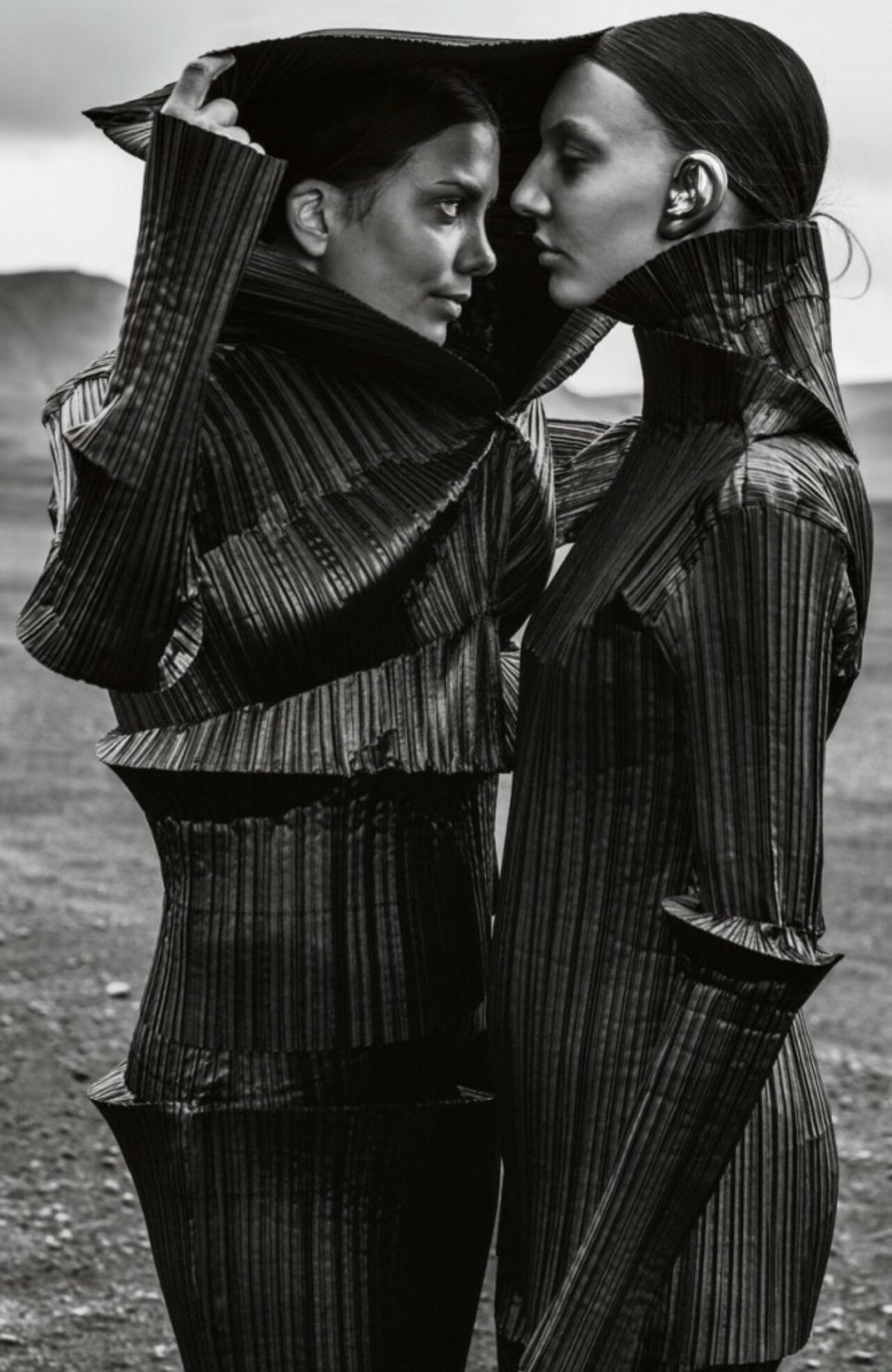

In 1988, Issey Miyake began to explore garments with revolutionary micro-pleating or plissé, which would later be launched in 1993 known as Pleats Please. The profundity of these folds was not only in their innovation production, it allowed the wearer freedom in comfort and movement. Following this, A-POC “A Piece Of Cloth”, would also go on to transform the potential of clothes through advanced techniques. By utilising a single thread fed into a computer-programmed industrial knitting machine, the result revealed customisable tubular garments.

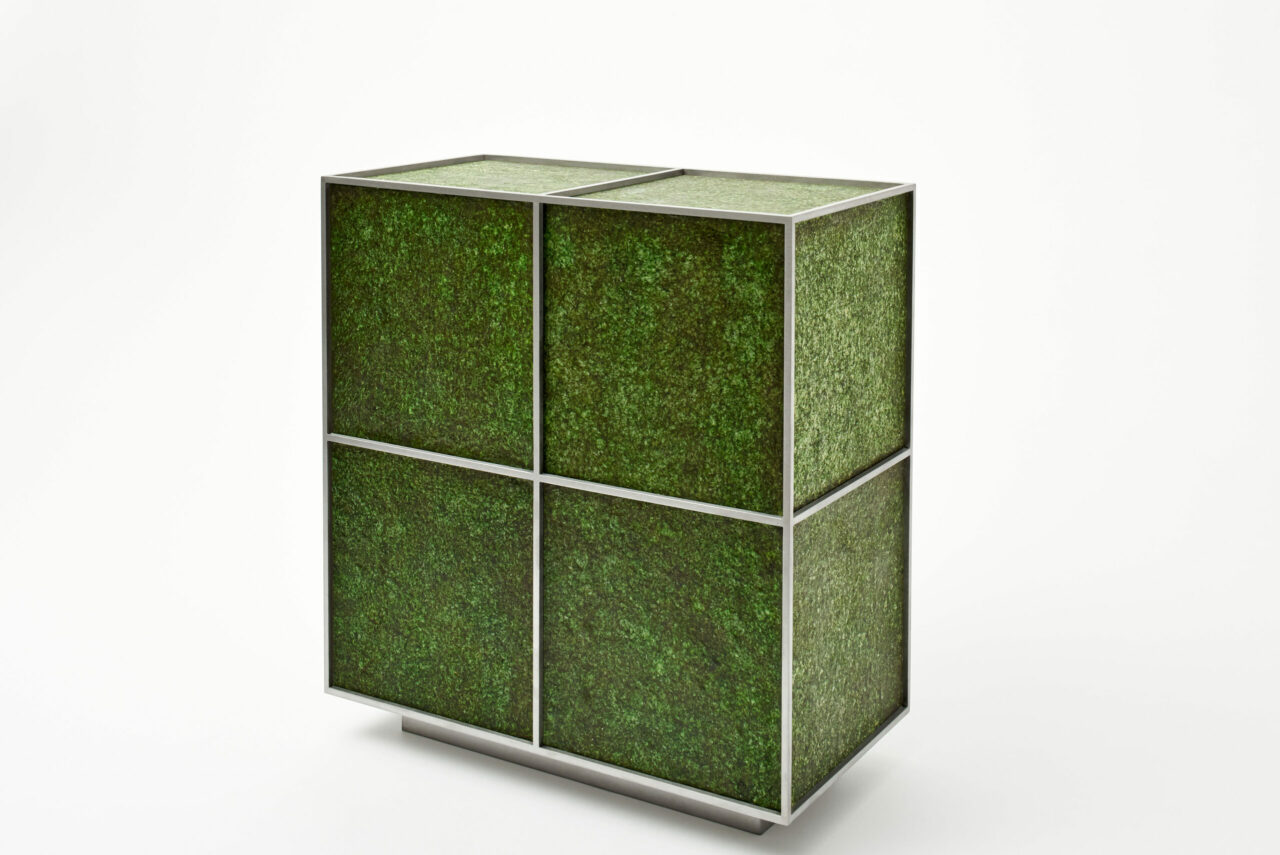

Yet it isn’t just the famed Pleats Please garments but the ongoing search for innovative solutions with advanced technology. Kazuko Koike, a long term friend and close confidante of Miyake, noted, “Miyake knows too that petroleum and crude oil are limited resources, and that it must be possible to somehow restore and reuse, even to upcycle them. This has become a mission for him, and he seeks to make clothing with enhanced ecological values.”(4) This, found in the 132.5 ISSEY MIYAKE line established in 2010, where a piece of 1-dimensional cloth takes on a 3-dimensional shape, then folded into a flat 2-D surface, and when worn, transcends time and dimensions as “5-D”. The line is made from recycled polyester, often an unknown fact yet one that truly showcases the value of Miyake’s great design thinking without over-emphasising any superficial marketing purposes.

Alongside clothes, Miyake had an equally astute eye and sensibility for identifying and cultivating extraordinary talent as his borderless collaborators, one such being Irving Penn who Miyake would simply send his new collections to photograph, without any direction, completely entrusting the photographer full freedom of photographic interpretation and maneuvering. Furthermore, Miyake would appoint some of the country’s most talented creatives for his seasonal collections; Naoki Takizawa, Dai Fujiwara, Yoshiyuki Miyamae, Yusuke Takahashi, Satoshi Kondo. The brand’s numerous design alumni have equally flourished: Kosuke Tsumura of Final Home, and both Tsumori Chisato and Mame Kurogouchi in leading their own eponymous labels.

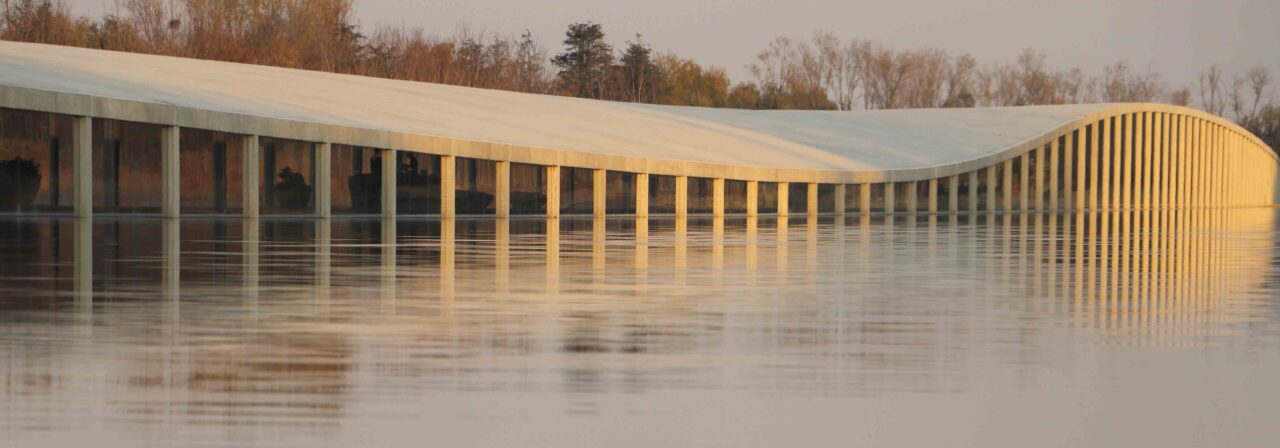

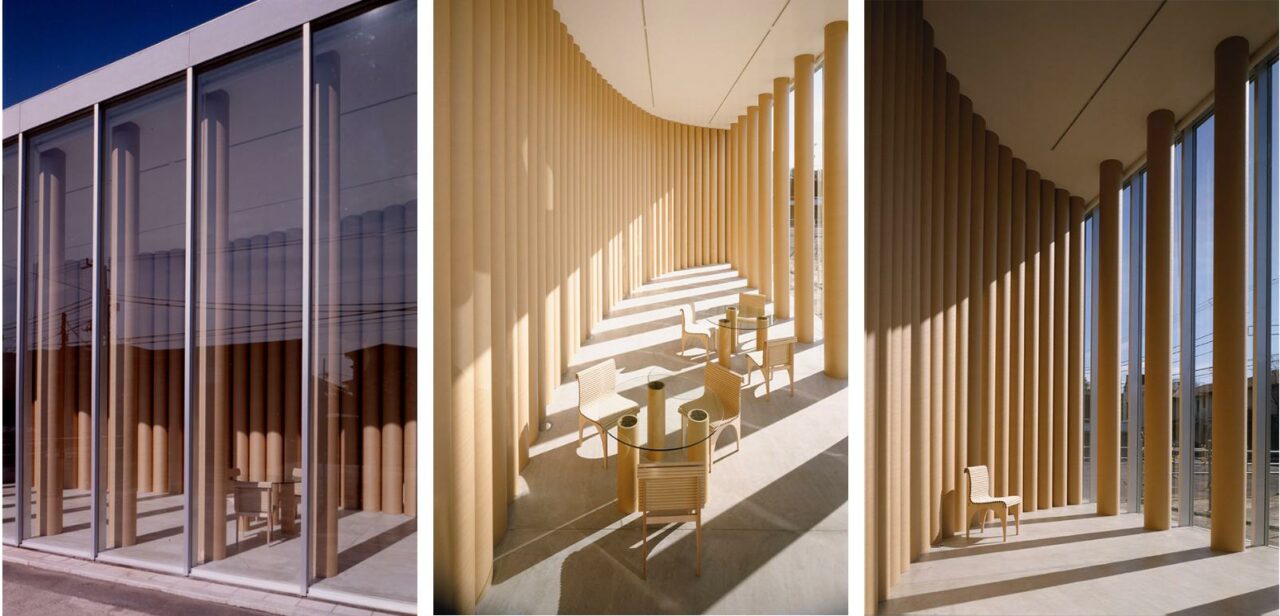

Miyake’s eye for exceptional collaborators extended to visionary interiors for his stores designed by Shiro Kuramata, Toshiko Mori, Ikuyo Mitsuhashi, Ito Masaru, Sou Fujimoto, Tokujin Yoshioka, Naoto Fukasawa, Shingo Noma to David Chipperfield and Ronan and Erwan Bouroullec. The all-encompassing spaces reflected their modern and innovative ethos of the brand. Not to mention the brief Miyake Design Studio Gallery in 1994 designed by architect Shigeru Ban, situated on an uphill road in Yoyogi Uehara with an interior and structure completely constructed with recycled paper tubes.

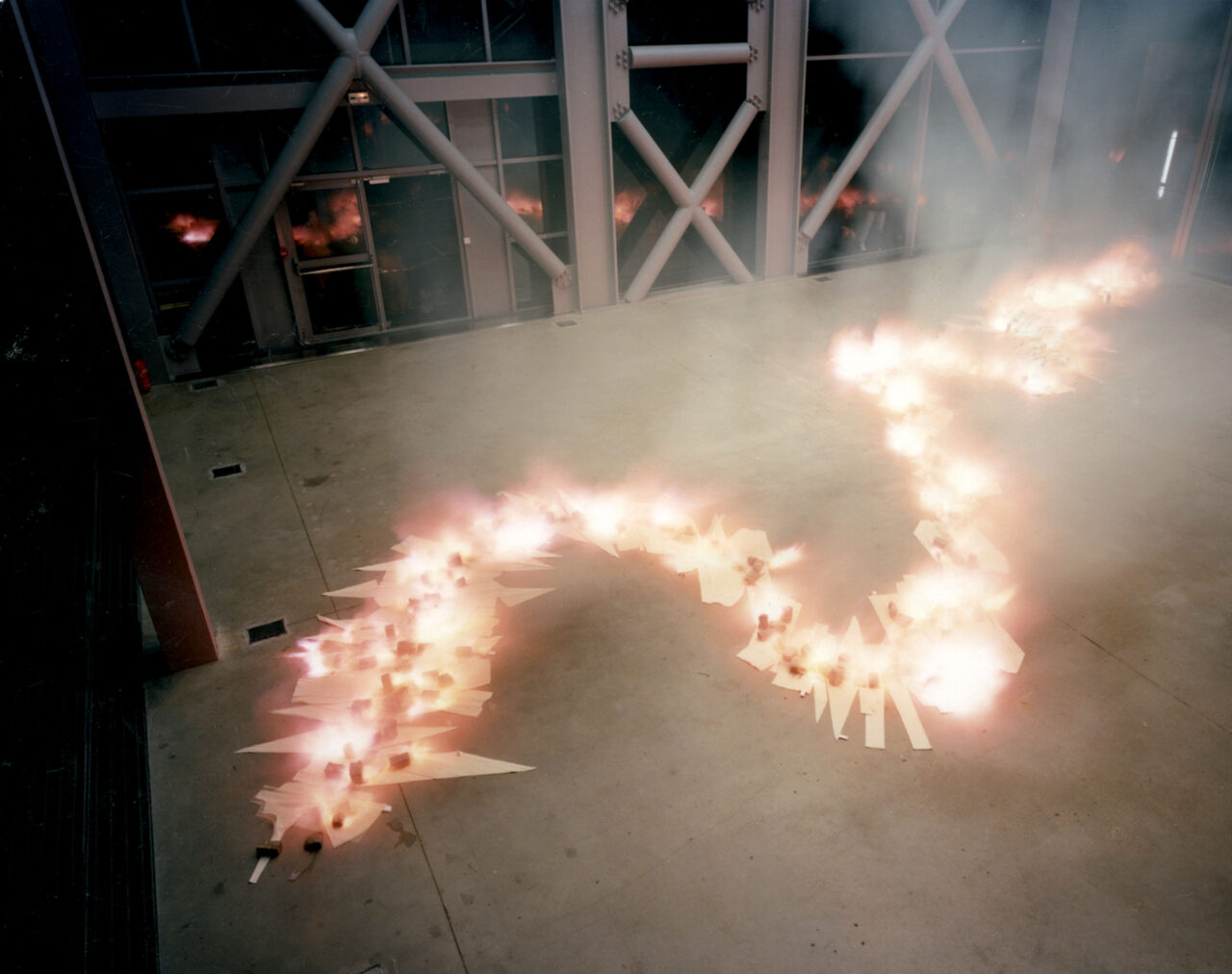

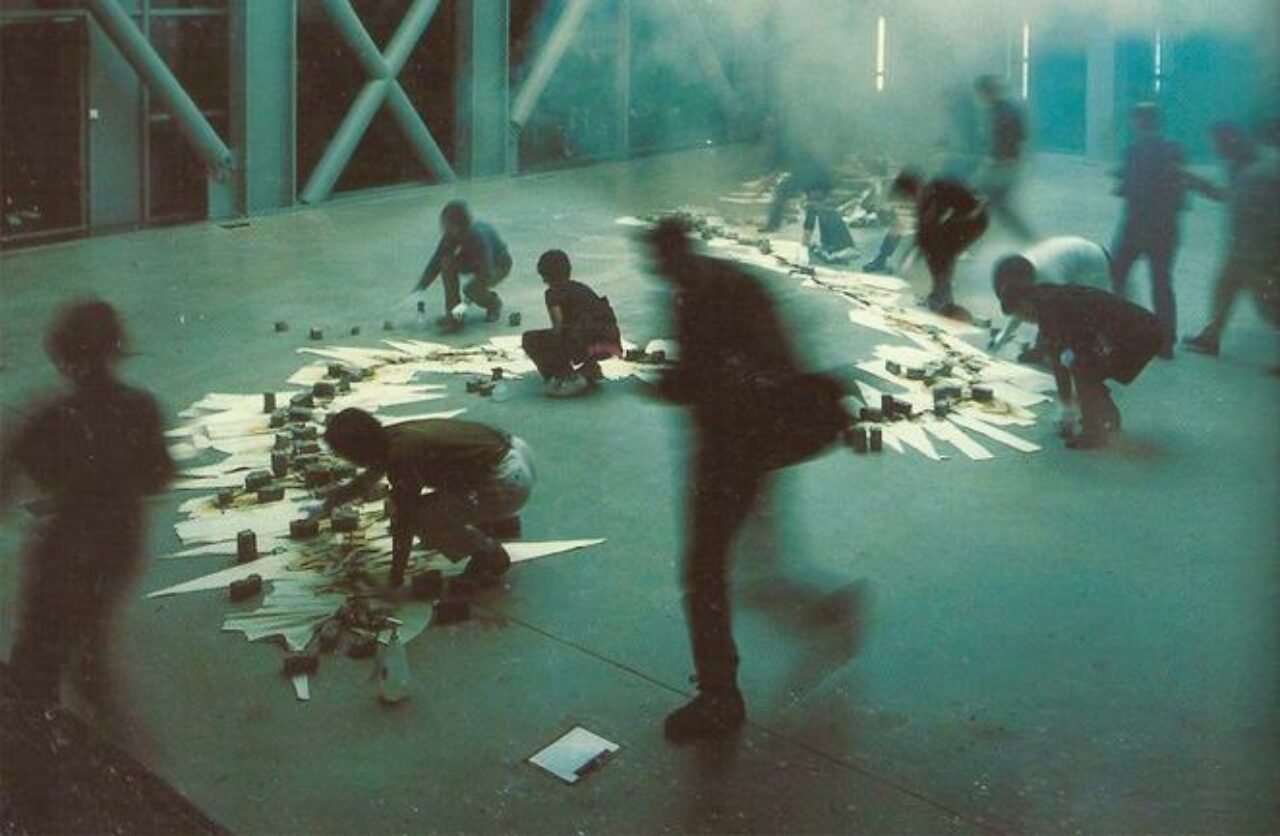

In the late 90’s, Miyake created a Guest Artist series that would see his garments merge with art by leading contemporary figures including Cai Guo-Qiang, Nobuyoshi Araki, Yasumasa Morimua and Tim Hawkinson. Miyake’s intention was to create an “interactive relationship” between the appreciation of art in a new, sculptural form through wearing works directly on their bodies. Through this, wearers interacted with fashion and art simultaneously.

Artist Cai Guo-Qiang’s recently reflection on his friendship and 1998 collaboration with Miyake: “Issey gave me total freedom straight out of the gate. For a while I thought of creating “clothing with herbs” that would boost the physical and psychological health of the wearer. Then I talked a lot about feng shui clothing to bring the wearer good fortune. In the end my efforts were stymied by practical limitations: for example, clothing must be able to survive being washed. Thus I returned to my old standby, gunpowder. Naturally gunpowder presents problems of its own, since clothing fibers tend to burn easily. I racked my brain for a means to explode the garments without burning away the fabric. The burned holes had turned out to be nearly unavoidable, but it in turn led to an extraordinary breakthrough – we even printed patterns of scorched holes on printed fabrics. Every time I see my artworks – the exploded Issey Miyake garments – not in a museum but worn on the street or at a party, I feel as if I am witnessing art in motion. These “spontaneous works of performance art” bring me an inexplicable sense of excitement!”

Yet it is also Miyake’s understanding of the value of art that can be traced back to his Spring/Summer 1997 Collection’s Paradise Lost dress and coat featuring a print by Tadanori Yokoo. Yokoo, 41-years-old at the time, would go on to design the artwork for every ISSEY MIYAKE seasonal collection invite starting from the Paris Collection in 1977 and even continuing to this day, some 45 years later.

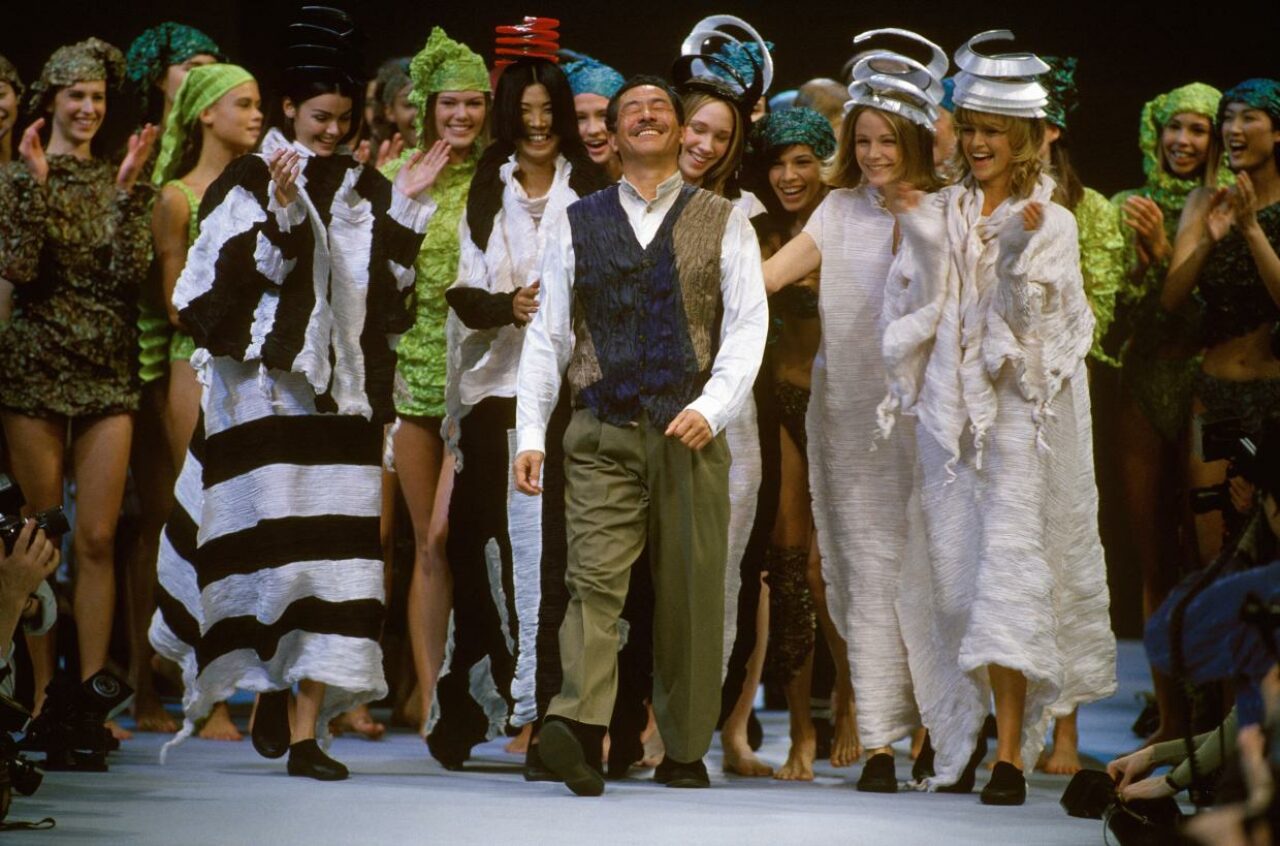

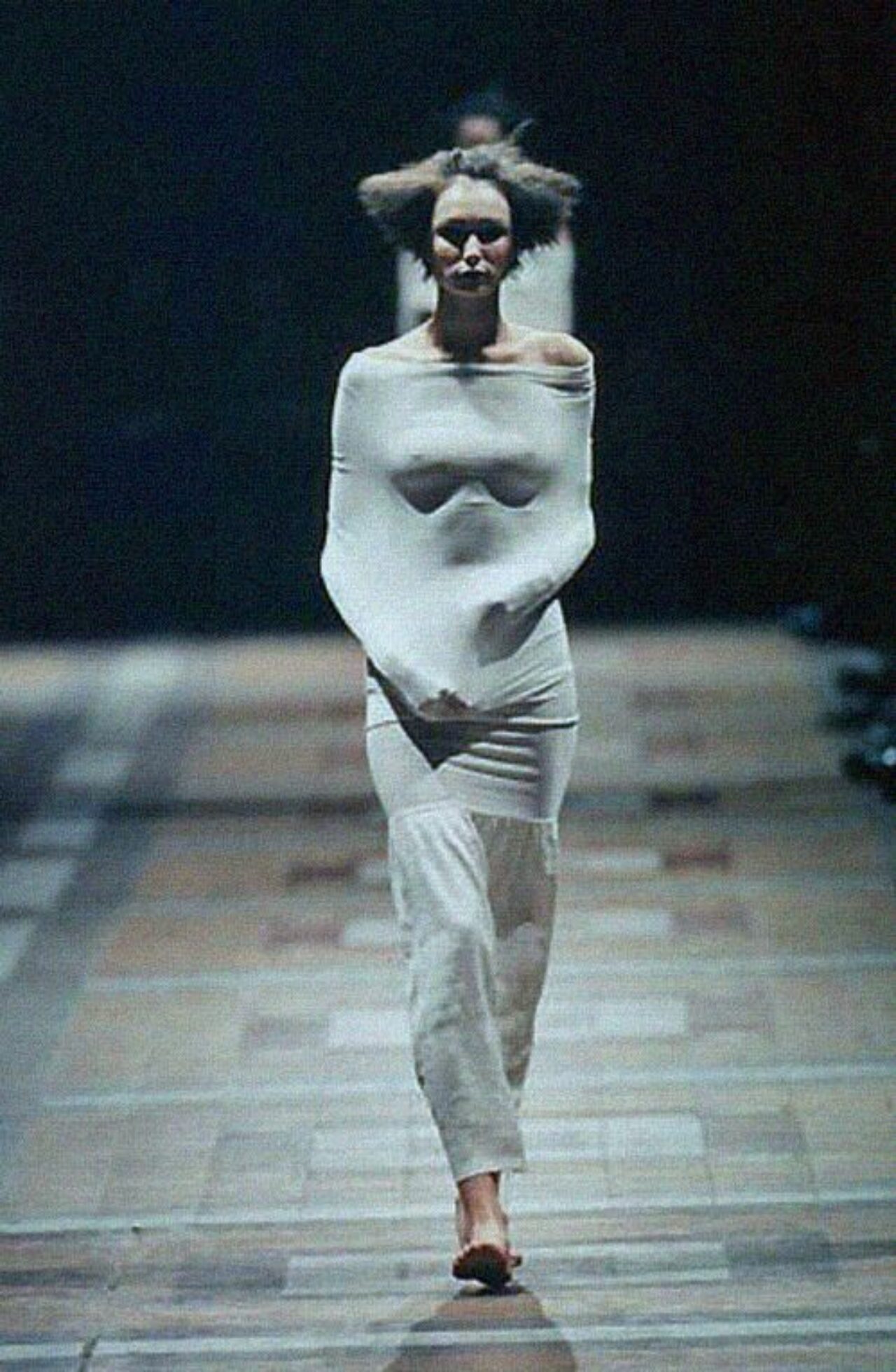

Expressing the freedom of clothes also took form in the unconstrained locations, models, personalities and their movements in Miyake’s collection presentations. Gliding with confidence or jumping and dancing, Miyake was never short of inviting professional dancers and acrobatics teams to participate in his shows. Always filled with playfulness and joy in their execution, it was also in his Spring/Summer 1977 that Miyake was the first designer to ever stage a fashion show in a museum. Architect Arata Isozaki noted this in his entitled essay, Thinking on The Wild Side under the headline “Issey Miyake’s Work Is A Cultural Incident”. (5) From his Autumn/Winter 1977 collection, his presentation Fly With Issey Miyake on a cross-shaped runway, to even holding his 1992 ‘Twist’ exhibition at Naoshima Contemporary Art Museum — even before it was renamed as the Benesse Art Museum — consisting of only Pleats and Twist garments to showcase their original shape and production technique.

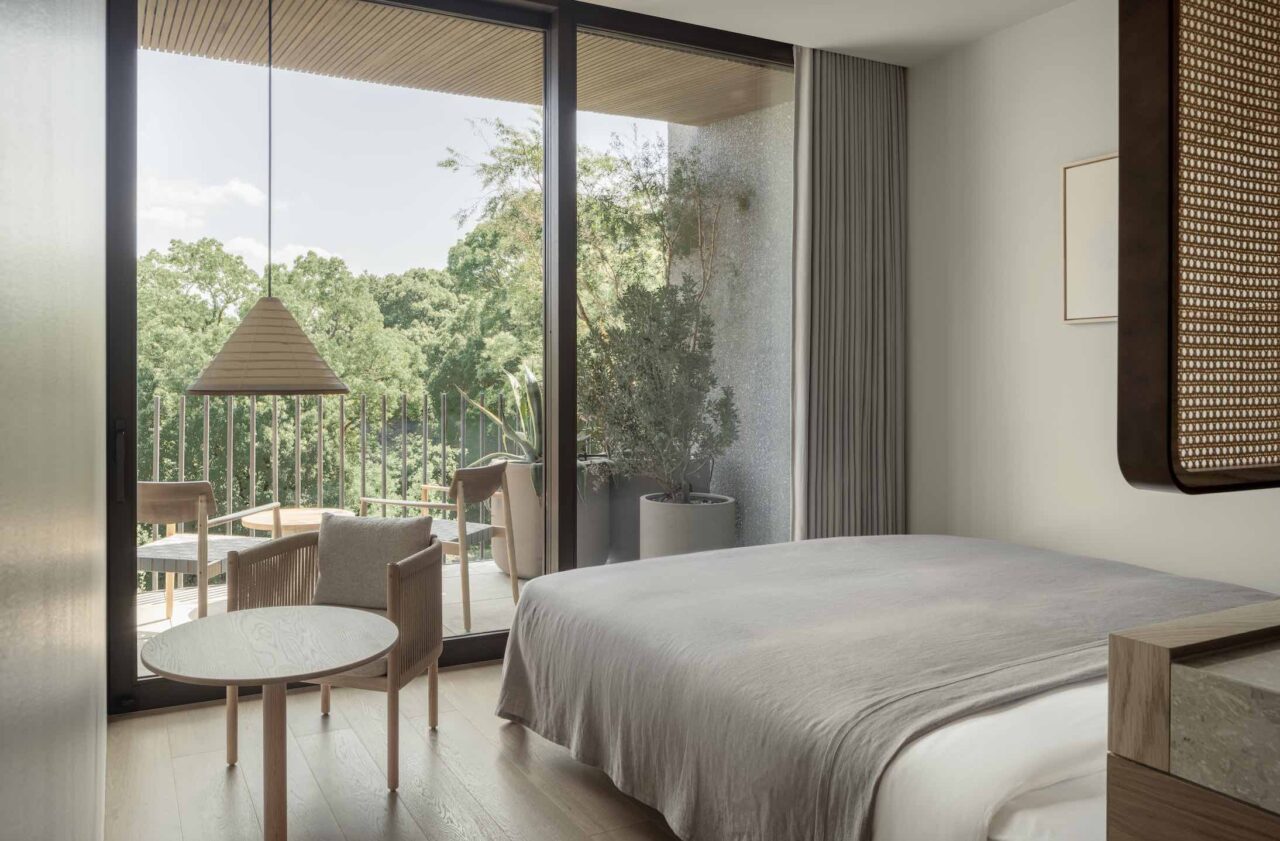

Miyake held an enduring campaign of the great value of “design” in Japan, such seen in his letter in the Asahi Shimbun in 2003, which inevitably led to his establishment of Japan’s first design museum: 21_21 Design Sight with associate director Noriko Kawakami and directors Taku Satoh and Naoto Fukasawa. The subterranean structure designed by Tadao Ando is just as unprecedented as the mind-expanding exhibitions shown inside.

It was an honour to write about all things ISSEY MIYAKE on Ala Champ. From listening to him speak with such enthusiasm and rigour for his work at his retrospective in Tokyo in 2016 (and his desire to explore the potential of paper garments which resonated deeply with me), to the many different threads I would come across here in Japan that would all lead back to Issey-san, revealing just how influential he was to the creative tapestry here. It was only in deeper conversations here that I would discover that he was irrepressibly and modestly a key connector in the intersection of Japan’s creative landscape. One such example being when Masatoshi Izumi’s family noted that it was Issey-san — as his friends and colleagues would often refer to him also — who suggested Ikko Tanaka to design the visual identity of the Noguchi Foundation Japan.

My own journey of connecting with the expanse of Miyake’s clothes came with my move to Tokyo and witnessing their stellar quality and longevity of textiles and true practicality in design. When delving back into the archives, one can find forgotten lines including ASHA, Permanente, Plantation, FETE, Issey Miyake Men to IM Sport, reflecting the company’s impressive five decades of evolution. Now find the current lines under the Issey Miyake group counting PLEATS PLEASE ISSEY MIYAKE, BAO BAO ISSEY MIYAKE, 132.5 ISSEY MIYAKE, HaaT, me ISSEY MIYAKE, HOMME PLISSE ISSEY MIYAKE, IM MEN and APOC-ABLE.

Importantly, he was always interested in, and in support of, the younger generation. This is best reflected in the stellar team that he, alongside longtime friend and associate Midori Kitamura — now President of the Miyake Group — have built, found within the company. Satoshi Kondo, now artistic director across the main lines, and Yoshiyuki Miyamae leading a team of engineers for the experimental line APOC-ABLE, focussing on new possibilities of clothing.

It’s extraordinary to look back on the amount of creation one individual can bring into the world in one lifetime. Whilst his trajectory was wild and untamed, his altruism as a designer to simply aim to create great clothes for the everyday person is the key factor. Design led by a human-based approach embedded with joy and the celebration of life.

Rest In Peace, Issey Miyake, an exceptional individual to have graced and created so much for us on this earth and one whose visionary design thinking will continue to inspire generations to come.

Text: Joanna Kawecki

Images: As credited

footnotes

(1) International Herald Tribune, 1992

(2) Icon Magazine, 2011

(3) New York Times Magazine, 2009

(4) “Where Did Issey Miyake Come From?” Kazuko Koike

(5) Mainichi Shimbun, 1977