HENRIQUE OLIVEIRA

Challenging Perceptions Of Sculpture And Painting, One Of Brazil's Most Celebrated Artists Combines Nature, Art And Architecture To Create Monumental Works

Henrique Oliveira’s work crosses the genres of architecture and art, challenging perceptions and labels of sculpture and painting. Primarily describing himself as a painter, Oliveira started with oil on canvas and is now additionally working with his own uniquely created style of painting, with wood. It’s an unusual description but one that makes sense when visually seen, as the artist transforms the wood he uses into a three dimensional painting. It is easy to see the connection, his adaptation and reuse of materials is completely original, with the pieces organically growing. This is not just a referral to the aesthetics of his work, but the way the work is created, processed and executed.

With constructions constantly taking place in his hometown of São Paolo, the most common wood used for building houses is often discarded, and left for reuse by others. Connecting the visual similarity of the wood when broken to a brushstroke, Oliveira started to explore the properties of wood, and in particular, the wood of discarded tapumes.

The language of Oliveira’s work is inviting, easy owing, and connecting. It is multi-lingual. In any context, the viewer can enjoy the works and then experience it’s message through experience. It’s elements are a reminder of society’s reliance on nature, and the artist’s dramatically modest approach is a comforting reminder of this.

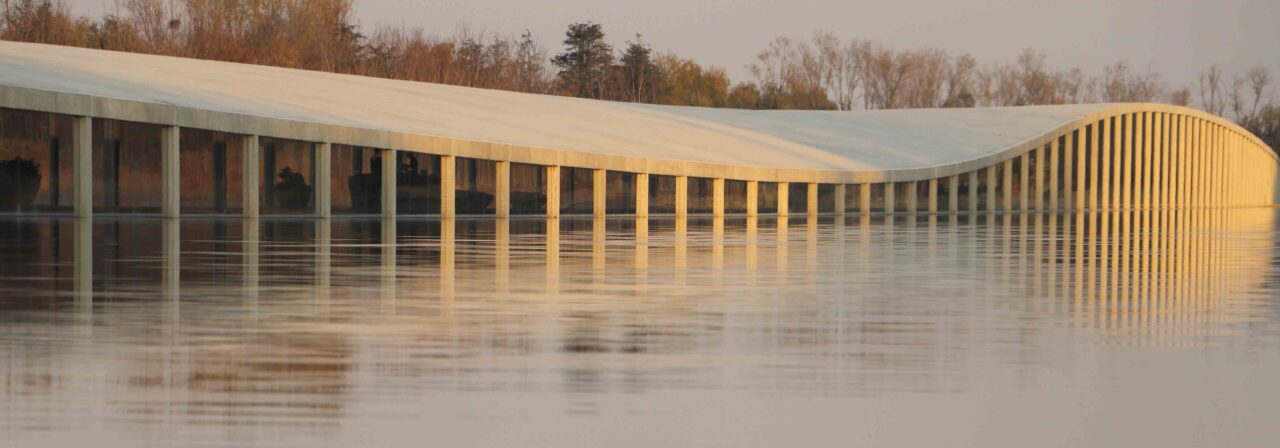

On a quick trip to London, we met the Brasilian artist at Duke’s in Mayfair, to converse in detail about his latest outside installation at the Centre d’Arts et de Nature in France, and his celebrated installation Baitogogo at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris.

Oliveira has been busy recently, with travels worldwide seeing his work created in new environments in various cities, allowing new audiences to experience their power in the flesh. He’s only about to get busier, so we took the chance to sit down and find out more about this elusive artist.

CHAMP | You have been traveling a lot this year we have seen, especially for your work in Paris at the Palais de Tokyo and Centre d’Arts et de Nature in the Chaumont-sur-Loire.

HENRIQUE OLIVEIRA | Yes quite abit. This year I have been outside of Brasil, because of this residency of 6 months. In July I went back to Sao Paolo to stay for 2 months, then needed to go to Frankfurt for another month, then back to Sao Paolo for another month. Coming and going. I go to Vancouver, and then to Miami soon.

Maybe this is an important element to our daily lives and whatever work we are doing. Your heritage is quite prominent in the works, incor- porating your history into the works and sharing them inter- nationally, such as by using the tapume wood.

Yes, but I don’t always use the tapume. I use other materials too. The tapume is very hard to nd outside of Brasil, used plywood you can easily nd. I have done projects in the United States where I used found mattresses, rubber, metal scrap and other found objects.

How did you begin to use the tapume, and recycle this wood in your work. Is it im- portant for you to use recycled materials and is this a conscious philosophy in your work?

What attracted me to this material (tapumes) was that it performs like brushstrokes I am a painter, and when I was rst creating at installations that were more like a collage in texture, I was working with wood layers in a process that was very much created out of a painting procedure. The wood worked like brushstrokes. Some stirs were broken, had jagged edges and they resemble the kind of dynamics that make me think about brushstrokes.

The surface of the material has the specific textures and memory of its previous use. My first works were first only using the colours that were found in the wood.

I would take them from construction sites where this plywood had been used as a fencing material. It had been painted, so it had different aged colours. In Baitogogo, I deliberately recreated the wood going back into nature. I recreate somehow the wood going back to it’s natural source.

Perhaps going back to its natural form also.

By means and form of the concept of the work, it goes back to this idea of nature. An image of nature, as it is not nature infact, it is only using natural materials. It is a return from its urban context to generic or organic shapes. In the case of Palais de Tokyo, I also used some tree branches to combine with the rest of the con- struction. I wanted to create a situation that you don’t know exactly what’s nature and what’s arti cial. The work also deals with this idea of controlling life and the impossibility of controlling life.

For me it also had a symbolic meaning, particularly in the structure that I recreated where I reproduced the pillars and the white beams that were corrupted by the strange nature, the idea of controlling life and the rationality and irrationality. There is a whole concept that changes with each project , even if I keep the same material and same technique, the idea is always changing, just like life.

When we first saw Baitogogo, it reminded us of architecture’s reliance on nature, with the two materials of manmade pillars and natural wood juxtaposed. It is nice though, that each viewer can interpret it in different ways.

There is no information behind the works, in the sense that you don’t need to know something to understand the work. Eve- ryone can enter and enjoy, and have a reaction somehow. The work can speak to people that also don’t know about art or contemporary art. They can nd other meanings or connections. In this way, the work is accessible to everyone.

Originally from a small town called Ourinhos, you currently live in Sao Paolo. Please tell us more about this city.

When I was 16 I moved to Sao Paolo because my mother wanted me to study in a good University. I’m always adventurous so I agreed, but I did hate it in the beginning! It took me 5 or 7 years to get used to Sao Paolo. I also studied abroad, studying English for 6 months in Cam- bridge. I did another two months backpacking around Europe when I was 19. I ended up going to the Middle East, Egypt then Canada. I did a worldwide trip for 1 year and then I went back to Sao Paolo. My mother pushed me to finish University, and I stayed studying social communication.

During the course I studied I took some painting courses with a friend of my mothers, because I had always been into drawing. I had painting classes when I was 21, 22 years old. When I was 23 I went back to my home-town and decided I was going to be a painter. I had a studio there, but later went back to Sao Paolo to start my career. Whilst there, I had classes with another impor- tant teacher, a painter – whom I had classes with for 6 months. In the end of that year, in 1998, I went to study at the Sao Paolo University. The University is like a town inside Sao Paolo. There is about 30,000 people living there, it feels like a little town.

Our past experiences are the stepping stones to where we are now.

I was saying that my work has a really strong relation to nature, and this could be from my hometown where I grew up, where I was kayaking and camping. I have always been an observer of nature. When I moved to Sao Paolo it was a more urban life, and I started using this urban material. At the beginning my work was more geometric where I found I was recreating places that I had been. Slowly the side of nature came out and I got more into these organic constructions.

Tell us more about the material you use, tapume.

I don’t find tapume anywhere in the world, so I need to import it. In Brasil they use this material because it is very cheap. In Europe I have noticed that they don’t use materials which you can discard. They use plastic, metal and other materials which are reliable. In Brasil they produce these wood boards in a very cheap way. They use them, but they get rotten very quickly. After 6 months, the rain and the sun damage it and it starts to fall apart. They they change the boards for new ones. That is how I obtain the discarded materials. Ofcourse things are changing, and more and more they are substituting this tapume for more durable materials.

You mentioned you started working with oil and canvas. Do you continue to do so?

Yes I never stop to do so. I paint in my studio in parallel with the other sculpture works and the installations. I’ve shown the paint- ings many times, but I don’t exhibit them as much as the installations as they are always made especially for an exhibition-basis. The paintings I do are more intimate in my studio. They sell for collectors mainly, whereas installations are more for institutions. The site-specific installations are usually temporary works.

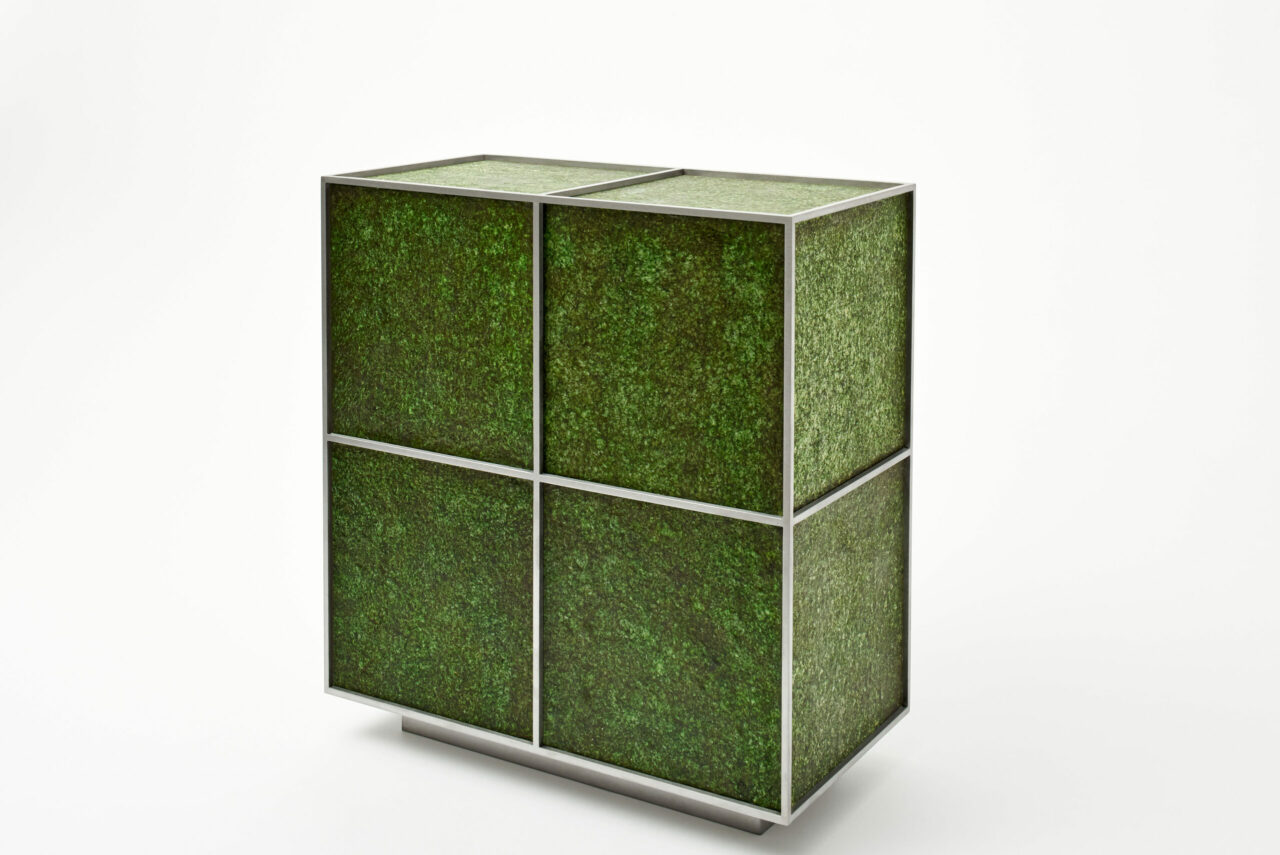

The sculptures I do are similar to installations, but on a smaller scale, and are produced in a different way. They can be installed, or uninstalled many times.

We look forward to visiting your installation at the Centre d’Arts et de Nature.

It’s a lovely place. It is about 2 hours away from Paris. It is like a museum. The castle there is very beautiful, and they have surrounding houses about 400m from the Chateau which are beauti- ful. It has an interesting history.

For my installation there, I had a chance to start work earlier, and I aways prefer that. In this case, I have plenty of time. I am more comfortable to work in this situation. I had a similar situation when I was in the States last year, in Cleve- land. They were creating a new building for the Museum of Contemporary Art, and I was able to start working before the building was nished. I had 2 or 3 months before the Opening to start on my exhibition. It is very good when this can happen.

Did visit the Centre of Arts and Nature before this?

Yes, I was at their vernissage this season in April. I was in Paris doing a residency project, for a project at the Palais de Tokyo. I came in January, and stayed in Paris until July. It was a 6 month residency, to create a project and by that time the residency that was hosting me said they would prefer that I do my exhibition at the Centre des Arts et Nature the following year.

Is this when you were invited to Paris by the SAM Art Projects?

Yes. It is a private residency. They created this residency to host artists from outside the axis of Europe-USA. The artists stays for 6 months, and they work the whole time dedicated to the end project that is a solo show in an Institution in Paris. It’s a great project, and the work to help this artist to be known in France. Lunches are organised every month with gallerists, collectors, curators, other artists and journalists. They do a good job. The place that I stayed in, was amazing. A very beautiful French studio with a glass facade..

Above a boulangerie…

(Laughs) Around the corner from many patisseries…

The perfect residency! So you’re installation at the Palais de Tokyo, was part of the Nouvelle Vague show.

Yes this Nouvelle Vague show was also in other places in Paris. They had 53 exhibitions, and they called all these exhibitions Nouvelle Vague. Did you see the installation at Palais de Tokyo?

Yes, this was where we first experienced your work. You main installation at Palais de Tokyo, Baitogogo, was quite the standout piece in the group show. When you physically experience it, the connection between viewer and the artwork becomes full circle. It is nice to recommend artists and their works to others, but you really need to see most works in the flesh.

Baitogogo was custom made for that space.

With your work mostly site-specific, what is your process of approaching each project?

It depends on each case. I have a sketch-book and I make sketch projects and ideas for imaginary places or generic places. I also work oppositely, and go to the space and see what can be done. I work with what the curator proposes – a room, or a gallery, or maybe a building outdoors.

Your work unintentionally has an emo- tive repercussion on the viewer after experiencing the work. Do you think this is important for art to have some sort of affect on the viewer?

Art is something that compliments the nature of the humankind.

It is something that doesn’t have a pur- pose in the sense of a utility, or something useful. Art in general, not just vis- ual art, music and literature for instance, they all have a purpose of complimenting the way human beings behave and need something else. We are cultural beings.

Art is part of this existence, a way of looking at the soul of the human.

It provides a different way of seeing.

It involves a lot of these aspects.

The perception of our surroundings, ourselves and society. The relation with nature also. What moves me, when I am creating works, is that I never think about how people will view them. I attend to what I am curious to. I am curious to see the result of that action and what is going to happen when I create something. We create something responding to our own demands and our own wishes and curiosities. We consciously and subconsciously know that other people will see it. Would you make art if you are sure nobody would see it? Is it something we do for ourselves, but knowing that someone else will see it. I think this is an essential question.

∆∆

Interview Monique Kawecki | London Editor-In-Chief

Photography – as credited

With Thanks Tom Budding

Published in print issue Champ Magazine 8