ISAMU NOGUCHI

"From Sculpture To The Body And Garden" At Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery

A monumental exhibition highlighting the work of renowned Japanese artist Isamu Noguchi has opened at the Tokyo Opera City Gallery, titled ‘Isamu Noguchi: From Sculpture To The Body And Garden’. Presenting a wide range of the renowned artists’ works, from his hand-brush paintings to sculptures in shigaraki stoneware and cast iron vases and landscape design. Showcasing both familiar and unseen or unaccessible works, the exhibition includes drawings and sculptural models spanning his entire oeuvre.

As one of the largest Noguchi exhibitions to date, it is a concise overview of the expanse of Noguchi’s works, presenting an in-depth look at the American-Japanese artist’ progression and innovation throughout his career. Divided into Exhibition Chapters segmenting the artists’ significant years and works, the exhibition presents a timeline overview of Noguchi’s growth and exploration in various materials, collaborations and site-specific landscape works, both in Japan and abroad. The gallerys exhibition design and navigation is key to note, with a stellar curation and placement of works creating an intimacy between viewer and object. Here, the atmosphere is zen-like, just as Noguchi himself would have intended.

Beginning with Chapter 1 ‘Dialogue With The Body’, Noguchi’s early exploration of abstract and fluid brush-paintings are shown, influenced from his time at his Paris atelier and close study of Constantin Brancusi in 1927, to his unexpected visit to Beijing (then known as Peking) in 1930-31. During this time he had created hundreds of traditional ink-paintings that merged figuration and abstraction, and eventually played a significant role towards his sculptural works. This included the uninhibited terracotta and plaster sculptural works which showcasing moulded facial and head sculptures of notable subjects and various New York socialites including Suzanne Zeigler (writer and copy-editor for Harpers Bazaar, Vogue, and House and Garden) or composer John Alder Carpenter.

Upon returning to New York, this was when Noguchi began creating stage set displays, most commonly in collaboration with dance choreographer and movement pioneer Martha Graham. Noguchi’s younger sister Ailes Gilmour was in fact one of the first members of Martha Graham’s newly-established dance company and would soon introduce Noguchi to Graham in 1929. Their collaboration would continue for 30 years, where Noguchi would create set designs for Graham’s performances, including Phaedra and Seraphic Dialogue. Presented in the gallery are original film and photographic captures, including Noguchi’s intricate sketches of each stage set study.

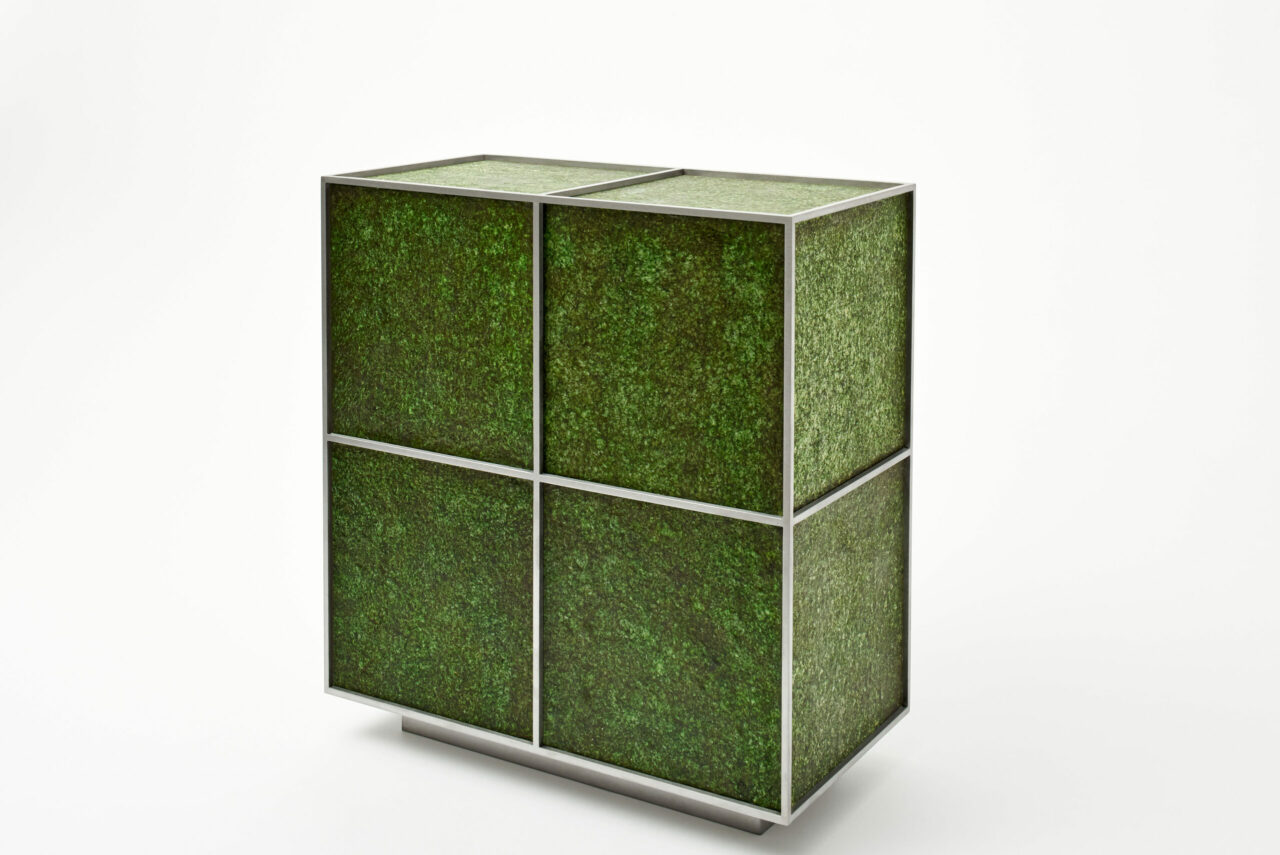

Noguchi’s diversity in materials for his hand-sculpted works crossed shigaraki stoneware with oribe glaze to cast iron vases. His sculptures reflect a truly pure imagination; from works symbolising a helmet or sculptural fence, to a three legged vase. The possibilities of silhouettes are explored here without restraint, where Noguchi’s hand-moulded works hold a life and imagination of their own. In Noguchi’s ‘Avatar’ (1948), it is a stoic, interlocking bronze Surrealist sculpture made from three elongated forms (representing a fish, tortoise and boar), that transforms what could have been a 2-dimensional work into a more curious 3-dimensional piece.

Amongst the gallery rooms, one small corridor-like space presents a pensive space for an unrealised model for “Memorial of the Dead”, a work that Noguchi was asked to create in 1952 in memory of the 1945 Hiroshima atomic bomb. The public art sculpture remained unrealised, and although rejected it was replaced with a monument designed by the building’s architect Kenzo Tange, Noguchi still envisioned to realised the work in the US. He explained, “Nonetheless, I decided to study how my sculpture might be executed from large blocks of black Brazilian granite. I had the notion that such a memorial might be meaningful somewhere in the United States as a gesture of regret and a sign of opposition to this devastating event. I also felt that Hiroshima itself would be needing a cenotaph in stone to replace the concrete shell structure designed by Kenzo Tange which had become damaged by time.”

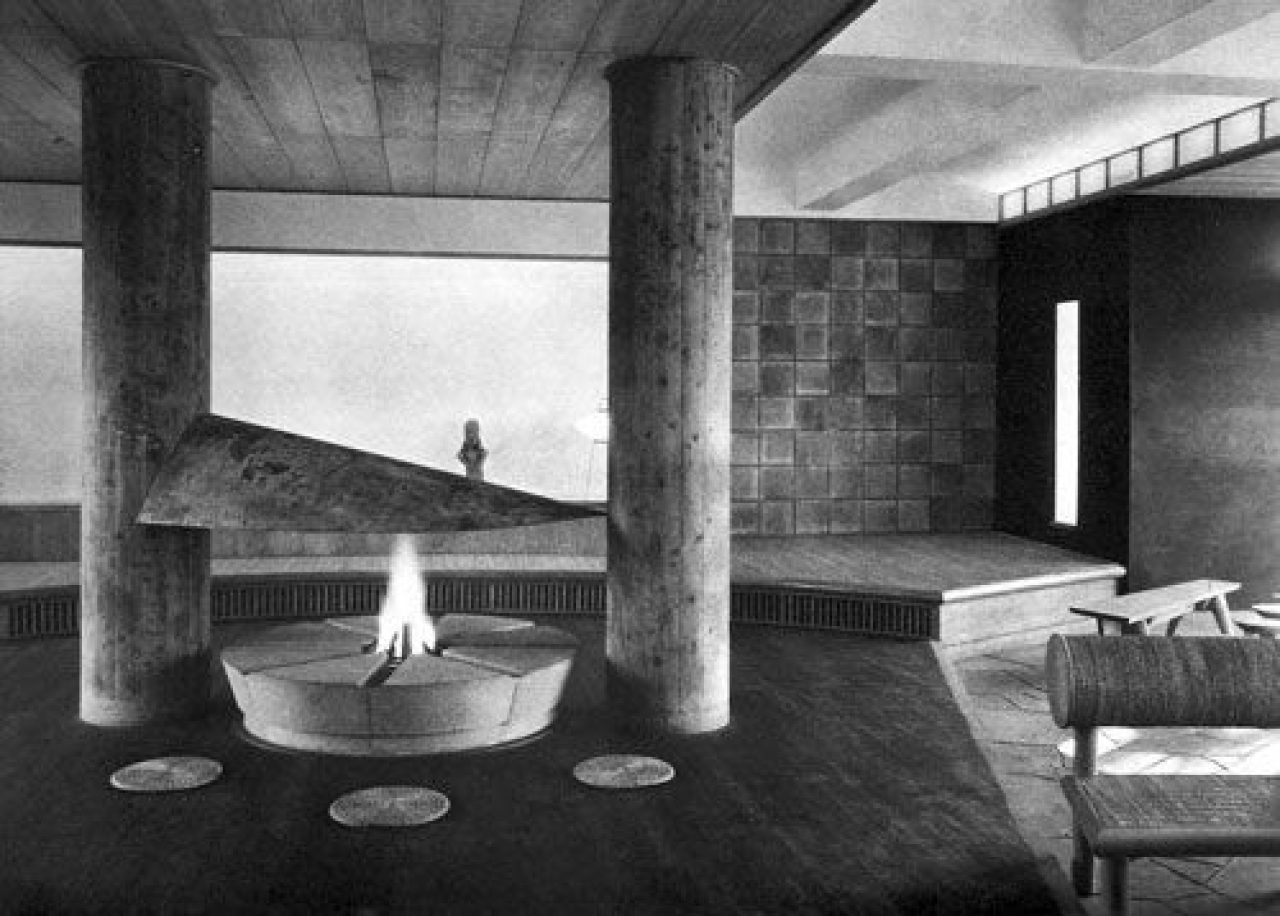

Chapter 2 sees’ Noguchi’s ‘Reunion With Japan’, where in 1950 he returned to explore and re-connect with his father’s homeland and it’s traditions that would go on to later influence his product, landscape and furniture design, architectural interiors, and famed ‘akari’ hand-made lighting. During this time he established key collaborative relationships with ceramic artist Rosan Kitadeo or architect Yoshiro Taniguchi, highlighting Banraisha in Keio University (where Noguchi had created a space and accompanying furniture in 1952) with sketches of a proposition for the “design of the second laboratory” and the University’s west and north interior with Taniguchi.

The gallery’s central space presents an entire room devoted to Noguchi’s Akari light sculpture series, handmade from Japanese washi paper, from table and ceiling lamps to an installation of a monumental 2-metre-high lantern on display. This rare and large-scale work made from traditional Japanese washi paper, bamboo and wood was created in 1985 and is usually found residing in the Isamu Noguchi Garden Museum Japan.

The exhibition’s Chapter 3 ‘Sculpture In The Space To The Garden’ section looks at Noguchi’s large-scale garden and landscape sculptural works. These works intended to bridge “sculpture” and “earth”, with an aim to reimagine the human body in relation to the ground and his ongoing fascination of gravity. Here, hand-sculpted landscape study models are presented in plaster and bronze including Play Mountain (1933) to Contoured Playground (1941) or The Tortured Earth (1943) in Magnesite. Here Noguchi’s intention of play; both within and with his model sculptures is found. It’s clear to see he worked with the strength of his body and hands to create the works of various sizes, but a sense of playfulness was always embedded in their design.

Noguchi balanced an interplay of West and East, and was heavily influenced by the zen gardens in Kyoto, such as the Hojo South Garden at the Daitoku-ji Temple, or the rock garden at the Ryoanji Temple in Kyoto. Japanese rock gardens “kare-san-sui” or “dry landscape gardens” focussed on the beauty of stones and sand, reflecting nature in relation to the universe. Noguchi designed a modernist take on the concept, creating stone-oriented gardens at Paris’ UNESCO building in 1958 to Tokyo’s indoor stone garden “Tengoku” (Heaven, 1977) at Sogetsu Kaikan in Akasaka.

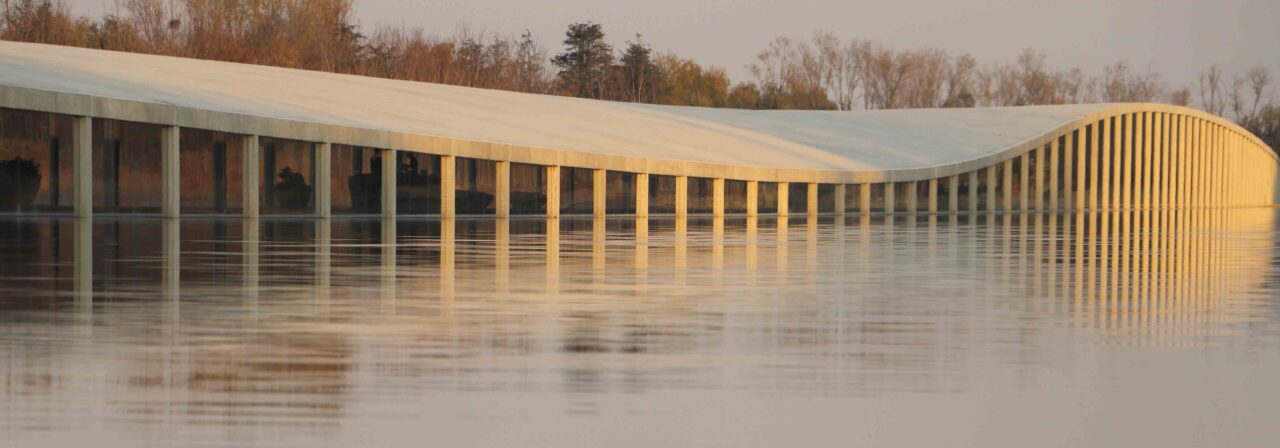

However in his East meets West approach, Noguchi’s stone gardens featured water. This integrated Japanese aesthetics with Western modernism and was an entry and exploration in “sculpture from water” seen in his subterranean water garden Sunken Garden at the Chase Manhattan Plaza, a meditative and contemplative space viewed from above or at ground level enclosed by a curved glass wall. The New York garden features black boulders sourced from Uji River in Kyoto, surrounded by a floor of tiles intricately placed to resemble raked stones similarly found in a dry landscape garden. Noguchi had stipulated that he “…I have never been interested in doing a Japanese garden per se” which sees the garden re-contextualised to feature an integrated water fountain feature in the summer season.

In 1966, Noguchi met his greatest collaborator and friend, local Stonecutter Masatoshi Izumi based in Mure, Takamatsu in Japan’s Kagawa Prefecture, highlighted as Chapter 4 ‘Sympathy With Nature – Stone Garden’ of the exhibition. It was said that when Noguchi had arrived in Kagawa, he had asked around for the best stonemason in the area and was introduced to Izumi, who was known for new architectural and artistic uses of traditional stone cutting techniques. From his newly established atelier in Japan, which would later become the Isamu Noguchi Garden Museum Japan, he was able to complete larger works using Indian Granite to Basalt and together with Izumi, created some of the most ambitious sculptural, architectural and stone garden works to date.

The stoic and slender Maiastra Homage to Brancusi (1971) showcased Noguchis ongoing interest in the Parisian sculpture and the influence he had on his life work. In polished grey marble, it is a towering structure comprised of 8 diverse elements. Here the simplicity of each element’s composition is most intriguing. Oddly shaped and stacked upright, it was an homage to his interest in Brancusi’s own work and as Noguchi explained himself, “as a form of honesty to materials, the reduction to simple forms, minimal expression and the like, as key modernist values.”

In Phoenix, created in 1984 (four years before his death) the sculpture was made from Shodoshima Granite, a material most curiously and commonly used for headstones in Japanese cemeteries. One can only presume a link between the titled artwork and chosen material, in anticipation of the inevitable and at a time when Noguchi had reached 80 years of age.

The gallery’s final hallway sees a complete timeline from Noguchi’s birth to death, detailing key works and achievements; such as his close friendship with Buckminster Fuller whom he shared a fascination for technology with as key for future advancements.

Not only with you leave with a greater understanding of Japan’s most renowned sculptors and his diverse creative output, but with a wider sense of Noguchi’s ambition to seek resonance with nature and the universe.

Isamu Noguchi: From Sculpture To The Body And Garden

Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery

14 July – 24 September, 2018

#champ_tokyo

Written by Joanna Kawecki | Tokyo-based Editor In Chief