GENTA ISHIZUKA

A Studio Visit To The Kyoto-based Contemporary Urushi Lacquer Artist

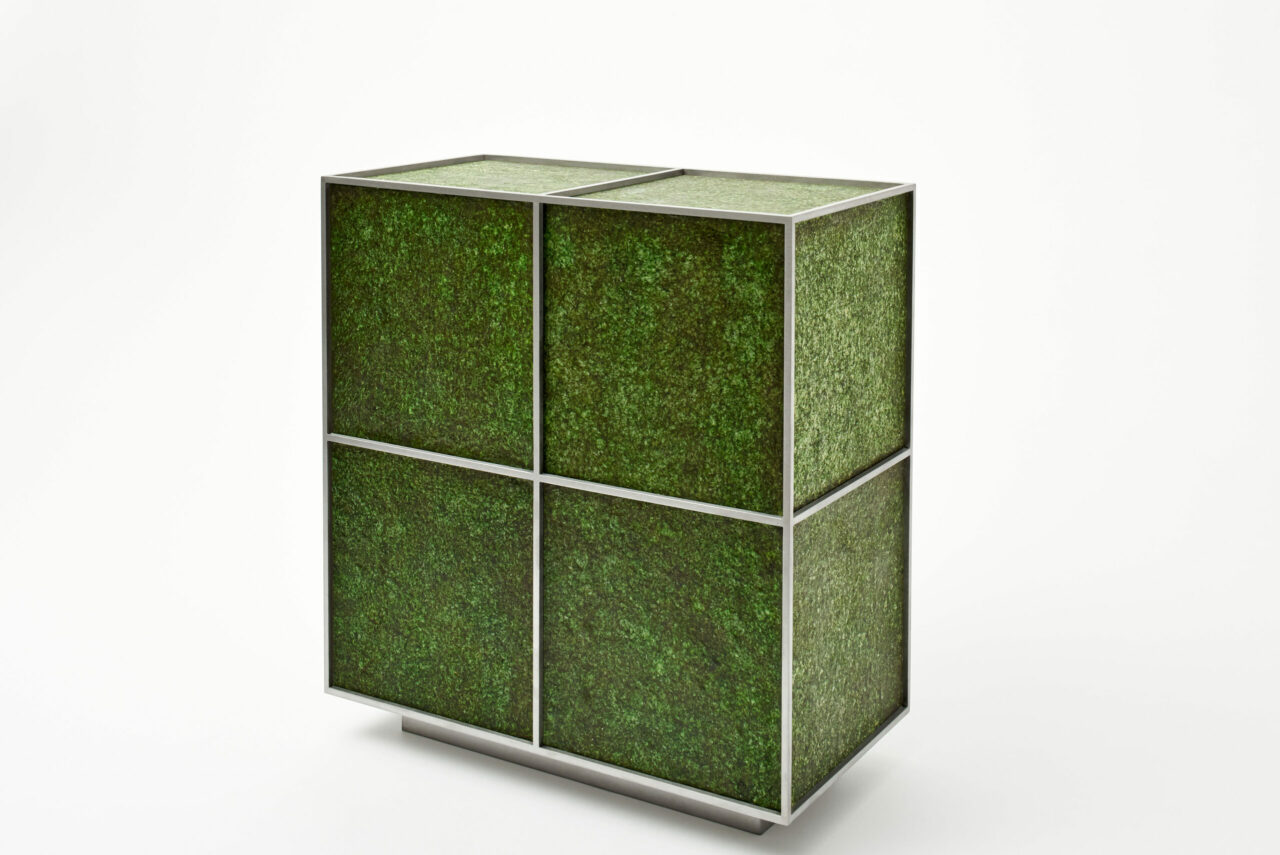

Many be familiar with Kyoto-based lacquer artist Genta Ishizuka’s deep red bulbous forms, displayed during Loewe Foundation Craft Prize 2019, the winner amongst 29 finalists. His gleaming red sculpture set a striking contrast against the Noguchi-designed indoor stone garden in Tokyo where the brand’s annual exhibition was being held. Ishizuka’s work SURFACE TACTILITY #11 presented a garnet-burgundy coloured complex that revealed a dense complexity and cosmos-like continuity both transfixing and illuminating. The artwork sat at a metre in height — a strikingly large structure for the laborious and time-intensive traditional craft — with its impressive form securing the Grand Prize.

With his work, Ishizuka focusses on the texture and tactility of urushi lacquer, utilising the arduous process and precious natural material; a traditional Japanese craft made from varnish sourced from an East Asian lacquer tree that is commonly applied to wood, paper or bamboo and was formerly used for its antibacterial properties of dining utensils, bowls and plates. Now, Ishizuka is using the material and technique with a contemporary view that sees it positioned within the contemporary art landscape. He is digging deep into historical pasts, whilst still modernising the craft.

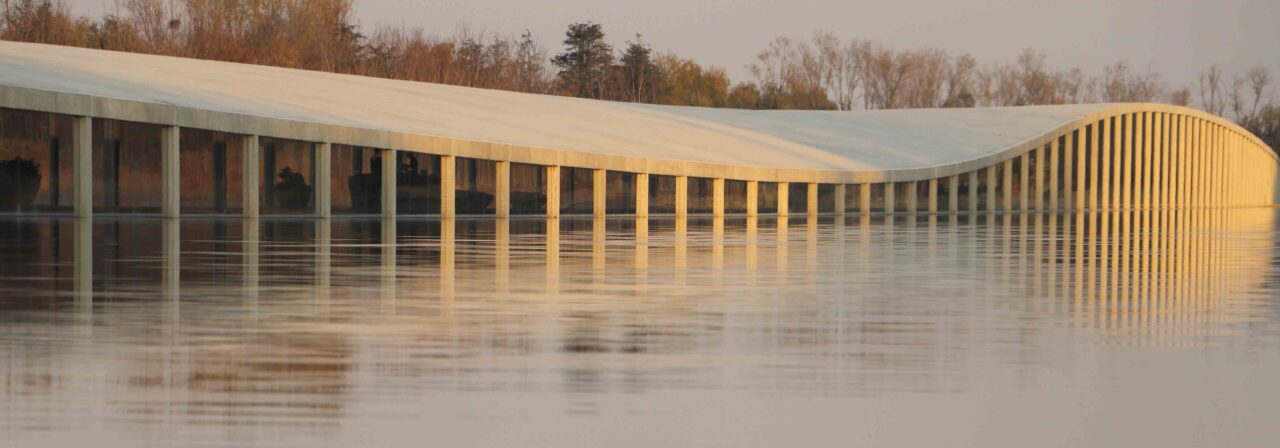

Visiting Ishizuka in his studio situated on the second floor of a warehouse building, it is a quaint space situated on the outskirts of central Kyoto located just behind Kiyomizu-dera, it’s remote location sitting amongst both residential and industrial properties. The brand new studio was renovated by Ishizuka himself only a year earlier — its spacious interior allows for his artworks to be both conceptualised and completely realised within the studio’s four walls. Inside, find studio desks for sketching and experimentation, a blank wall for exhibition and artwork planning, a large display table with neighbouring bookshelves, and most importantly, a self-built humidity and air-controlled, dust-free pavilion-like room where he applies the lacquer and dries the works. The room stores a small gas heater, tub of water and timer, alongside wooden stools that position the works.

Being Kyoto-born, it is no surprise that Ishizuka is heavily inspired by early 19th century woodworker and lacquer artist Tatsuaki Kuroda, who himself was born in Kyoto’s central district, Gion. Kuroda’s own works were equally transformative for their time and pivotal during the mingei folk art movement in Japan. Kuroda, like Ishizuka, created every element and the entire production process of his works — uncommon at the time — from carving timber to inlaying mother-of-pearl with dry lacquer surfaces. Ishizuka himself begins his process of initial sketches, miniature models, and then hand-forms his intended silhouettes from styrene foam, wood, stone, hemp cloths with various tools such as needles, mechanical pencils, wire to gold leaf — finishing with urushi and kanshitsu dry lacquer techniques.

From one window, the view from the studio overlooks a neighbouring main temple — witnessing the garden’s stunning seasonal changes. Visiting his Kyoto studio, we speak with Ishizuka on his process, the balance of tradition and modernity, and his upcoming new works.

Ishizuka-san, please share a bit about your production process from start to finish.

First, I pack styrofoam spheres into a bag made of elastic cloth to create a prototype. Then, I paste a linen cloth on top and apply the groundwork. This method of laminating linen cloth on a prototype is called ‘Kanshitsu’ (dry lacquer technique) and was actually used in the production of Buddhist statues in Japan in the 7th and 8th centuries. After the base, I repeatedly apply layers of lacquer to create a surface expression. After applying the last lacquer, I polish it with charcoal to make the lacquer glossy. The sphere that extrudes through the cloth creates the tension on the surface. I continue to repeat the same process, and then finally apply the last layer of lacquer to create a high gloss. This is where a tactile sensation with the lacquer intersects.

What are the main tools you use for your work?

For my lacquer work there are different tools required for each process; a spatula is used for the groundwork, a whetstone is used to polish it, a brush is used to paint lacquer, and charcoal is used to polish dry lacquer.

What is your uniform when working with lacquerware?

I usually wear thick t-shirts made of 100% cotton. They are comfortable to wear and easy to move around in. I particularly enjoy early spring to autumn when I can work in that style.

You are heavily inspired by another Kyoto-born craftsman Tatsuaki Kuroda, who was a legendary woodworker and lacquerware artist appointed as a Japanese living national treasure. How does his work influence you?

In 2000, when I was in the third year of high school I went to see Tatsuaki Kuroda’s solo exhibition at the Toyota Municipal Museum of Art with my father. At that time, I didn’t know about him, or lacquer or woodwork, but I remember that at my first glance of Tatsuaki Kuroda’s work I felt it conveyed the presence as sculpture and the strength of the materials of wood and lacquer. It was made for functional use, but also feels like a sculpture. There was also a presence of lacquer in the form that seemed to rise from two dimensions to three dimensions. It turned out that the wood, lacquer and the philosophy of Tatsuaki Kuroda are manifested in his works. When it comes to crafts and lacquer, I had an image of technique first, but I felt the generosity and strength that was not the case.

Is the use of lacquerware declining in Japan, and what is one way that such traditional arts / crafts can be maintained for the future?

Although I make new works using lacquer, I am also interested in acquiring old lacquerware to learn the history of materials, and also buy new lacquerware to study and collect too. I think it is important to be interested in and learn about the origins behind lacquerware, such as its history connected to wood and food culture. Most of the materials used for lacquerware require a timber base, so it is important to understand the combination of lacquer and wood is its main characteristic. Nothing compares to the lightness and mouthfeel when using lacquerware — the way that it transmits heat (such as when using it to drink tea or hot soup) is very unique too. In addition to that, I think that the sound of chopsticks and lacquerware hitting is very unique when eating a meal.

Please tell us about your new studio!

I moved into this studio in April last year. It’s a former metal factory building, and here on the third floor where my studio is now it was actually an office before. When I renovated the space, I dropped the original ceiling to create a higher one. I put up floors, erected new walls and renovated it all myself to make it easier to work inside. There’s a temple in front of the studio, and the cherry blossoms in front of the gate were so beautiful this spring.

What are you currently working on / upcoming projects for the future?

I just participated in Artstage Osaka this month, and a group show at ArtCourt Gallery in Kyoto last June. I’m also currently preparing for a two-person exhibition at CADAN in Yurakucho in Tokyo this October, and plan to exhibit three-dimensional works on the wall, as well as new series of works.