KENGO KUMA DESIGNS THE NEW V&A DUNDEE

Japanese Architect Kengo Kuma Has Completed His First Project In The United Kingdom, Designing The First Design Museum In Scotland

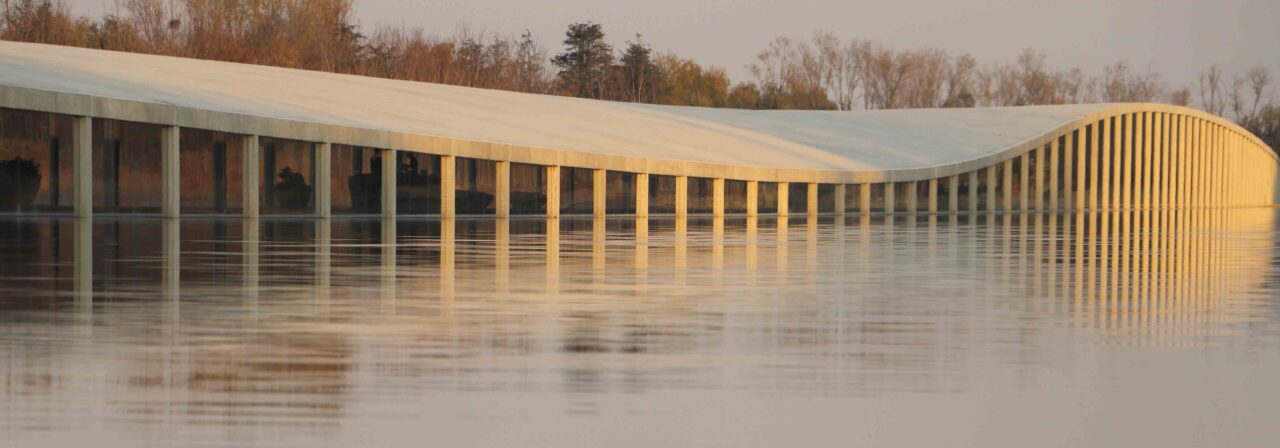

Japanese architect Kengo Kuma has completed his first project in the United Kingdom, designing the newly-opened V&A Dundee, Scotland. The stunning build is a geometric wonder, inspired by Scotland’s dramatic cliffs. Kuma has created a new cultural landmark.

Situated on Dundee’s Docklands, conveniently located just outside of the main station and fittingly next to the iconic Discovery ship, the new V&A Dundee itself looks like a vessel: it in in turn is also a pivotal example of ground-breaking engineering and innovative design, a testament to the industrial city and international port.

With the building underway since 2010, Kuma’s winning design proposal aimed to bring together “nature and architecture, to create a new living room for the city”. In his words, “I was inspired by the cliffs of north-eastern Scotland – it’s as if the earth and the water had a long conversation and finally created this stunning shape”.

Kuma’s design is made up of two buildings, intertwined. This can be seen when exploring the riverfront below the museum, as its pathway guide visitors around the monumental build. At the museum’s exterior, two different balconies showcase the breath-taking views of the River Tay and the crisp, sea air outside, whilst in the interior, landscape-format windows create postcards of the city with their specifically-selected viewpoints on the city.

The concept of creating a living room for the city has been executed, with the cafe, galleries, restaurant and gift shop all intrinsically linked to the centre of the building. This was the main aim for the museum, to bring the city’s inhabitants together through culture and design.

Celebrating Scottish heritage and culture with the permanent Scottish Design Galleries inside, over 300 works have been collated from the V&A’s own rich archives and private collections worldwide. The gallery design by ZMMA (an award-winning architectural and exhibition design firm based in the UK) is unconventional, working specifically for Scotland’s design history which is a continuous loop of modernism. Mills which previously loomed jute – a rough cotton – from India, now produce waxed cotton fabrics, such as the Halley Stevensons mill in Dundee. For the exhibition, the V&A Dundee acquired two of designer Nicholas Daley’s garments which showcase both jute fabric with waxed cotton detailing in a modern fashion. Scottish designer Christopher Kane’s AW15 lace dress is also displayed, alongside the iconic Fair Isle hand-knitted sweater which have received worldwide acclaim. Also in the Scottish Galleries, The Oak Room by Charles Rennie Mackintosh has been painstakingly conserved and reassembled by experts in Scotland by Glasgow Museums and the Dundee City Council. One of Scotland’s most important interiors, the 1907 tearoom design in warm dark-stained oak is one of Mackintosh’s iconic works. Originally designed for Miss Cranston’s Ingram Street tearooms in Glasgow, the entire work had been in storage for over 50 years.

The exhibition galleries within the museum, unlike the Scottish Design Galleries, will be ever-changing with national and international exhibitions. Also on the second floor, the auditorium, residency studio, learning studios and design exchange will constantly be activated with new displays and events. Across from all of these is the Tatha Bar and Kitchen, which serves incredibly fairly-priced seasonal, modern dishes.

To successfully create a living room for the city’s residents, their involvement needed to be incorporated from the beginning, ensuring they are comfortable – and proud – with the city’s new addition. This is exactly why the V&A Dundee team integrated the local residents into the museum’s build process since it’s earliest stages and have long-term projects created to continue to do so. These will be the V&A’s visitors for years to come, whom will also introduce their next generation to do so. These are the museum’s future contributors.

Aside from a temporary outpost Shenzhen, this is the first permanent V&A museum outside of London and also Scotland’s first design museum. Taking three and a half years to complete, the V&A is part of a £1 billion investment into the area, and the transformations are evident. The sleeping giant is being awakened with regenerations projects to revive the previously-thriving city once again. Situated on the coast, directly between Edinburgh and Aberdeen, Dundee has an immense amount of potential.

Right in the heart of the V&A’s living room we spoke to Kuma about his design process, the influence of nature on his work, and what he hopes for the future of Dundee.

ALA CHAMP: Kuma-san, when you first thought about this project, what did you want to convey with the building? Please tell us also about your original design proposal, the building was intended to be protruding into the water?

KENGO KUMA: I wanted to create a new type of building, in this special location. A normal artificial box will not fit, we thought. So we tried to create a kind of ‘land-form’ building. The land form for example; sea-cave, land or hills – that kind of land form can be the hint of new architecture. By using those ideas we tried to create a new type of organic architecture.

As a brief for the competition, we suggested to build half in the water. I liked that idea very much. But, for practical reasons – such as the water would be too strong – we [decided we] should draw back into the land.

Looking forward to this final design, we can still have some part of it in the waters and we can achieve the integration of water and land. I’m very satisfied with the final solution.

You’ve mentioned previously you have been inspired by Scottish architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh. How would you say that this building has been inspired by him, and can you reveal some of your other influences?

What Mackintosh achieved, as a new way of natural design. After Mackintosh’s so-called modernism movement, [he] went in a different direction. Modernism denies natural material and modernism is the best way to make industrial building. Mackintosh tried to create a new human design. His ambition was totally denied by modernism design after him. What we tried to achieve here, is to try to create a new type of human and natural design, as a hint that already exists in Mackintosh design.

One of my other influences is Frank Lloyd Wright. He designed the Falling Waters, and that is a good example of integration: water and building. Also Frank Lloyd Wright realised the big cantilever. This building has many cantilevers, and cantilever is the best way to create same-coverage space. Same-covered space is very comfortable. It can show a welcome gesture to neighbours. Also, the Japanese temple has many cantilevers. The big groove is creating shadows, big shadows protect natural light. I like that kind of device. We learn many things from them.

Please tell us more about your choice of materials.

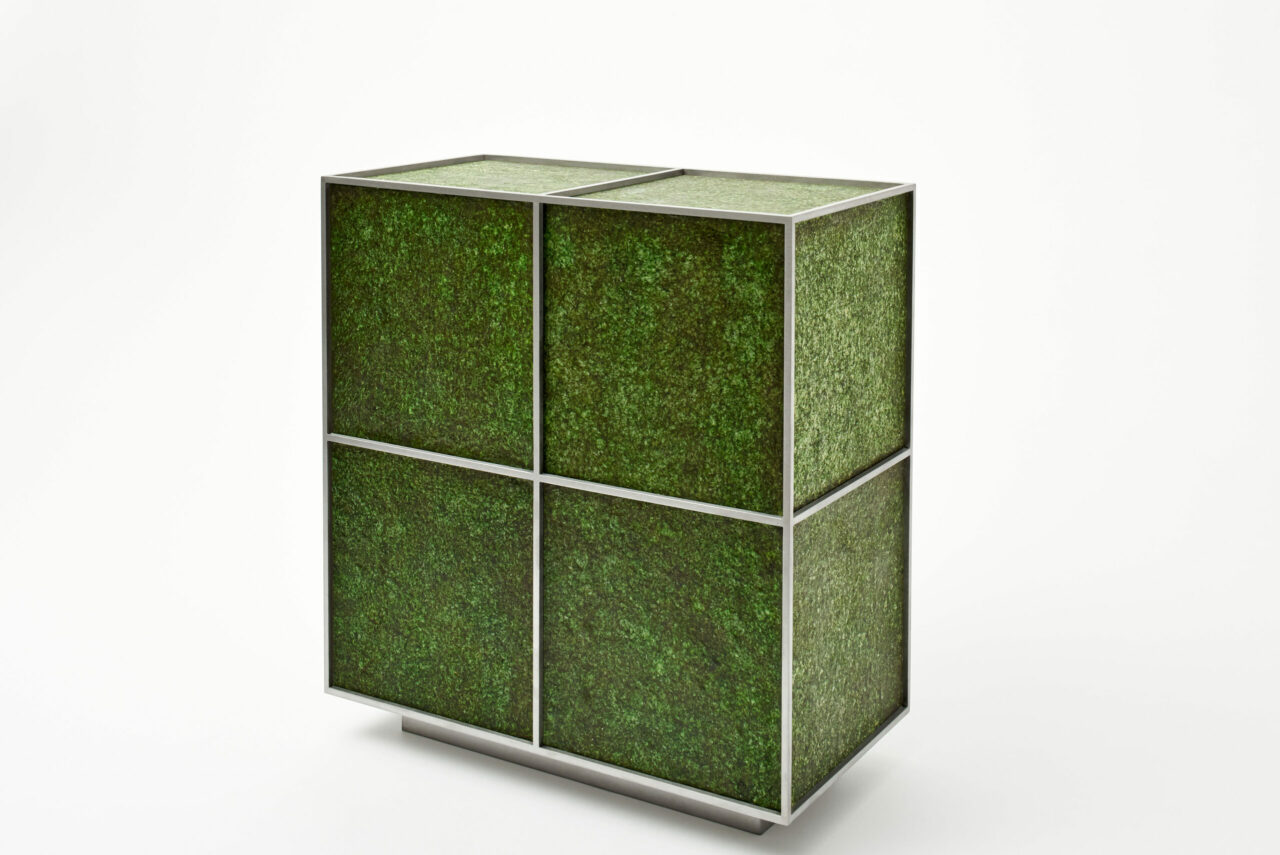

For the exterior, we did use pre-cast concrete panels as a homage to old building in Dundee. Old building in Dundee you see using dark stone. With dark grey stone, I like the colour of those old buildings. We didn’t want to use aluminium or glass, it is too shiny for the city. So, we used these concrete panels to depict the rough textures. The textures here are very unique. We used stone aggregate, and we washed it to expose the stone aggregate. Now it looks very natural, and very soft. For interiors, we wanted to add the warmness, because the idea for this space is to create a living room for the city. We thought that this is the most important space for the museum. Most of the museums use an entrance just as an entrance. The exhibition space is the protagonist of most of the museums, but for the community, the use of this space is very important. The people in Dundee can use this space like their living room. They can have tea, meet with friends, spend time with family. In this space. This space has warm materials, unique sections to make it feel wider than it is. This is the reason why I used oak, and this special detail [for the wall]. It has natural lesion, like the facade. Both have randomness and softness. It is very different from [a] normal industrial building. We tried to avoid it, the flash surface, and ‘repeating’.

The tiles throughout the museum are very unique, did you find them before you began building?

In the construction process, we found them. When I first saw the Irish limestone, with the sea shell and stone, I am so surprised, this is what I am looking for! The water is there [points outside], and this stone also reminds me that it is in the water.

Compared to other famous museums, what is most unique about this one?

The warmness. Most of the museums try to create a white cube, or an abstract or no-noise museum. That kind of white cube is good for photography, but for humans they want to live with noise and natural material.

Do you have a favourite part in the museum?

One is this big, open space, and the other is the cave in the centre of the building. That cave, will be the magnet to draw people into the waterfront. As schemes from other competitors, [they created] one single building.

The difference from us is that we have two different buildings, and we try to activate the circulation of people around the water front. When I was a boy, I was playing in the natural caves, it was my favourite for playing.

What do you hope for the future of the museum, and therefore the future of Dundee?

This museum can change Dundee. Dundee is historically connected with water very much. In the 20th century, the ocean and Dundee separated. With this museum, Dundee can find the ocean again. And I believe that can change the city drastically.

Words Monique Kawecki

Photography as credited

Thank you VisitScotland and partners