KŌGEI

Adhering To Strict Customs With A Twist Of Innovation - The Evolving Definition Of Japan’s Finest Craftsmanship And Art Form

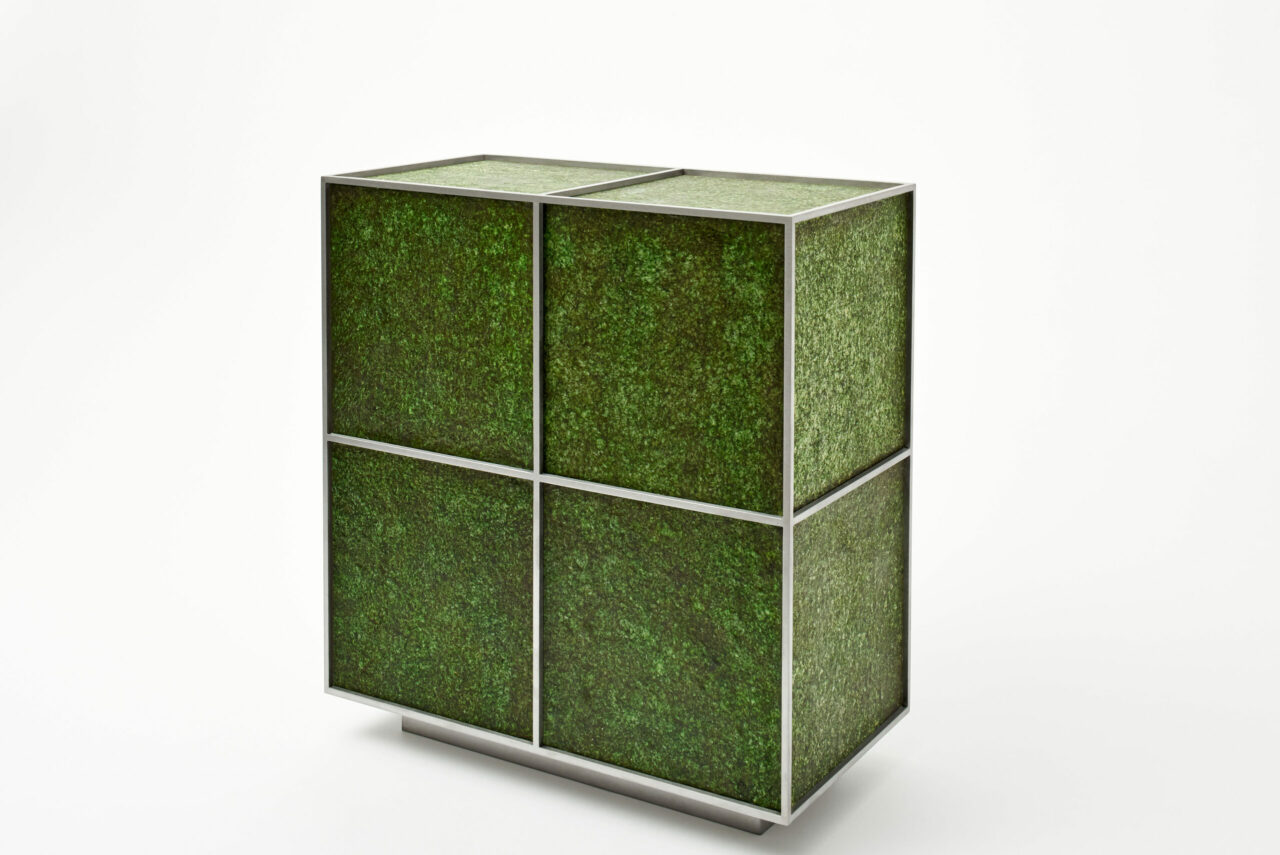

To understand kōgei (工芸), is to first understand its meaning. As an amalgamation of various descriptions, the centuries-old Japanese word sits most comfortably at the intersection of ‘highly-skilled craftsmanship’ and ‘artistic expression’ to describe the process behind the works.

In the late 19th century the distinction between the words “kōgyō” (meaning ‘industry’) and “kōgei” (meaning ‘craft’) was interchangeable, with both representing craftsmanship in Japan. The divergence between the two was later established through Japan’s industrial period in the 1860s, highlighting the evolution of craftsmanship itself. As Western civilizations became more and more industrialized in the early 1800s, Japanese hand-crafting continued to flourish through its refined heritage and aesthetics, with kōgei craftsmen later becoming protected under the Japanese government as National Living Treasures. Now, the meaning not only highlights the highest form of craftsmanship through a long lineage of centuries-old techniques, but a modern approach to them by a new generation of artists. Kōgei by default represents Japan’s history, although is not restricted by tradition to continue its evolution.

Whilst craftsmanship was embedded in Japanese culture and tradition, it held a varied value outside of the country. We sat down with Brian Kennedy, independent curator and craft specialist, during KOGEI Art Fair Kanazawa 2018 to speak about the evolving understanding of crafts and kōgei today. Kennedy notes, “In Japan, there was never that definition where there was hierarchy. Ceramics was always appreciated. Lacquer was, textiles…” Peter Ting, curator and product design consultant for craft and contemporary arts suggests an alternate viewpoint, “I personally believe that the Japanese system is so unique that it has been preserved for so many years because it’s been kind of closed off.” Ting continues to highlight the nuances even throughout Asia; “[In China], it was not about craft, it was about who made better quality things. Whereas in Japan, you could make the most superb quality ceramics or lacquerware and were appreciated as a living treasure, [which was] not so evident in China.”

Contemporary crafts also hold a wider definition globally, mostly subjective, across various cultures and nationalities. Kennedy reflects upon the Western understanding of the definition of kōgei and crafts, and notes the terms modern positioning in relation to current outputs. “What’s interesting in Europe, and particular the UK is they are not as big into heritage craft and contemporary craft. Heritage craft would be basket-making that’s derived from a local tradition, or a certain type of ceramics and would include things like what is it making; a much more functional kind of every day ready-usable object. Whereas contemporary craft is what I think that maybe is trying to become.” Kennedy explains a new move towards functionality with to reflect a cross-global accessibility. He notes, “That’s the kind of challenge I think when I see some younger glass, lacquer or ceramics glaze persons. Those I would see as being international and readily transferable and still have a Japanese flavor, however are not so tied to Japanese tradition.”

Where kōgei previously held a sense of perfection, now its makers’ creative expression is where it holds most value. Over-conceptualization and function take a side seat in contemporary crafts. The focus is on process and the act of doing, artists are liberated to create both functional and culturally-rich objects through the exploration of both materials and technique.

This also results in a more universal view of what type of ‘art’ it is, filtering down to the commercial sector often leading trends in the field to either open – or close – a wider understanding. Kennedy clarifies this, “The art world is now much more open to materials. The critics, and the writer, and the thinkers are thinking about materiality. So suddenly craft is now okay again because the language has shifted.”

The art world is now much more open to materials. The critics, and the writer, and the thinkers are thinking about materiality. So suddenly craft is now okay again because the language has shifted.

There are beautiful things that are made that move you at the same time as it having a substance that you can feel

Now, gallerists and collectors are acquiring the language of crafts.

Previously in its own market, we now see it merging with art fairs; critical to its survival. The role of the art fair can provide a commercial opportunity without devaluing the art form, even celebrating its vast history of master craftsmen and their invaluable knowledge. Kennedy acknowledges this, explaining the art market do know how to put a value on this, “That’s what the art world’s very good at. The craft world never developed that way of looking at the big figure, then looking at the spread of that. Looking at who did they teach, who taught them? How do we build a movement around that?” This storytelling is imperative to its justified value, cites Kennedy, “How do you place these five pieces in a museum? By putting them in a museum it makes them more important.”

New movements in the craft are resulting in a wider understanding and appreciation, with it effectively translating to a larger desirability. Kennedy notes the aesthetic interest from the art world influencing the popularity of crafts, “We have a different energy about how people are looking at work, and there’s a different language being used to describe work, and it’s including more people in it.” Continuing the evolution of crafts through a contemporary lens, Japanese artist Takuro Kuwata champions the craft of pottery and glazing with his modern take, proving extremely popular and sought-after by gallerists and museums alike. Kuwata is just one of the artists at the forefront of a movement blending tradition with modernity. Kennedy explains, “[there’s] a global contemporary movement that’s referencing the (glaze) material”. This is where Kennedy sees the art world embracing craftsmanship even more, through one ‘craft’ material at a time. “In three or four, five years time, it’ll be very common to see any of those materials and any of those artists that we would see as craftspeople at those level of fair. That’s the shift that’s happening now.”

A welcome shift, kōgei’s modernization is due to its open categorisation and definition, allowing it to exist under broader impressions in the art realm and beyond. Ting’s explanation of the art form’s physical and intangible qualities defines its timeless appeal, “There are beautiful things that are made that move you at the same time as it having a substance that you can feel”.

Text: Editor-in-Chief Monique Kawecki

This article was first published in February 2020, on Living Form.