Tokujin Yoshioka

The Laws Of Nature: On The Art of Light and Space With Japan's Leading Contemporary Artist and Designer

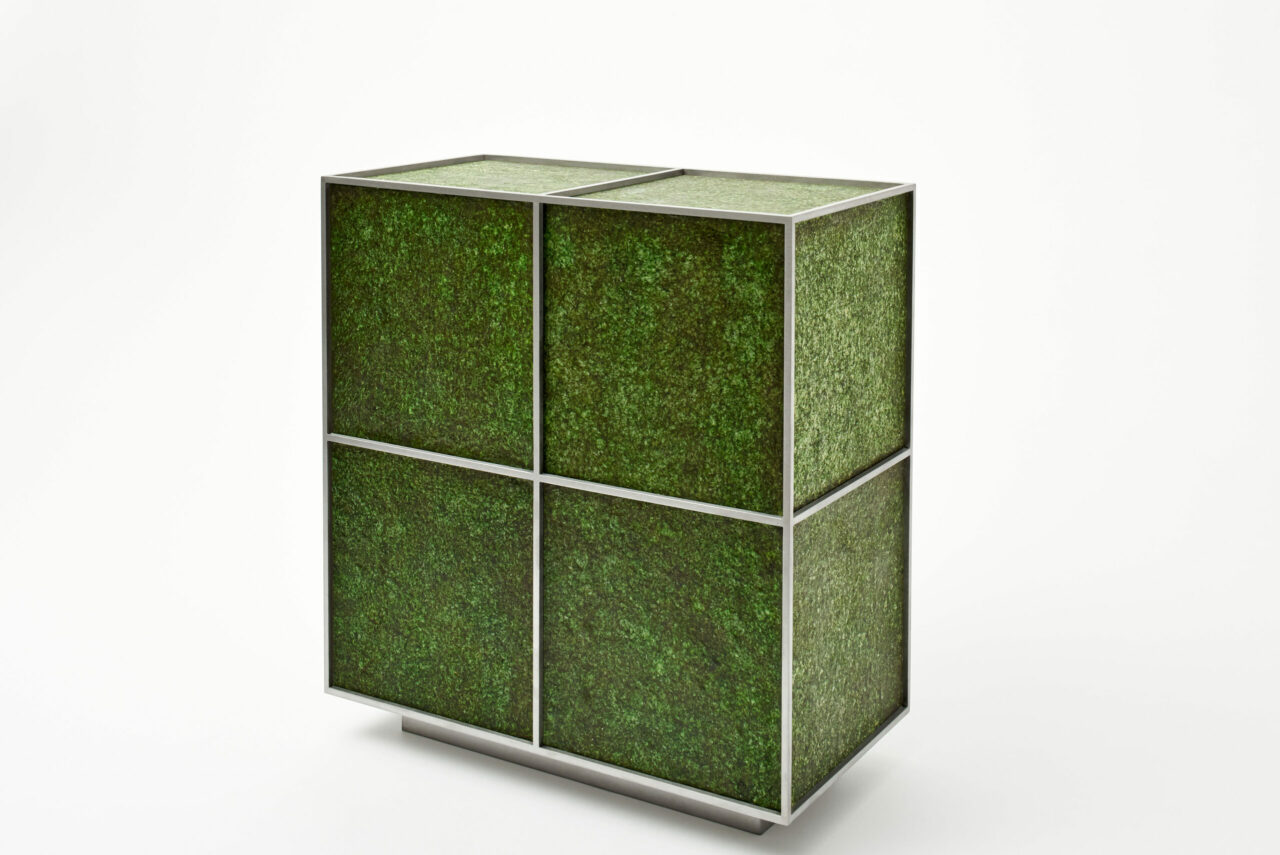

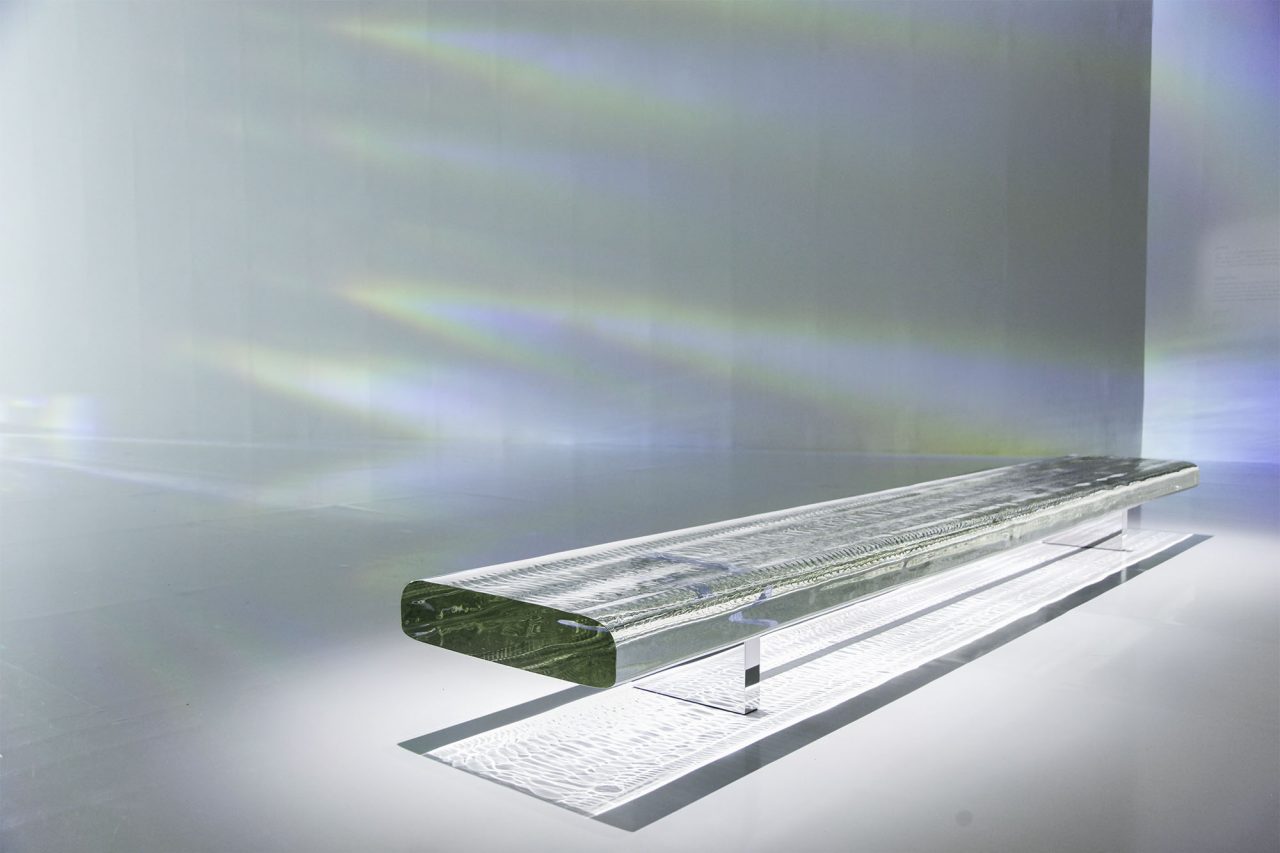

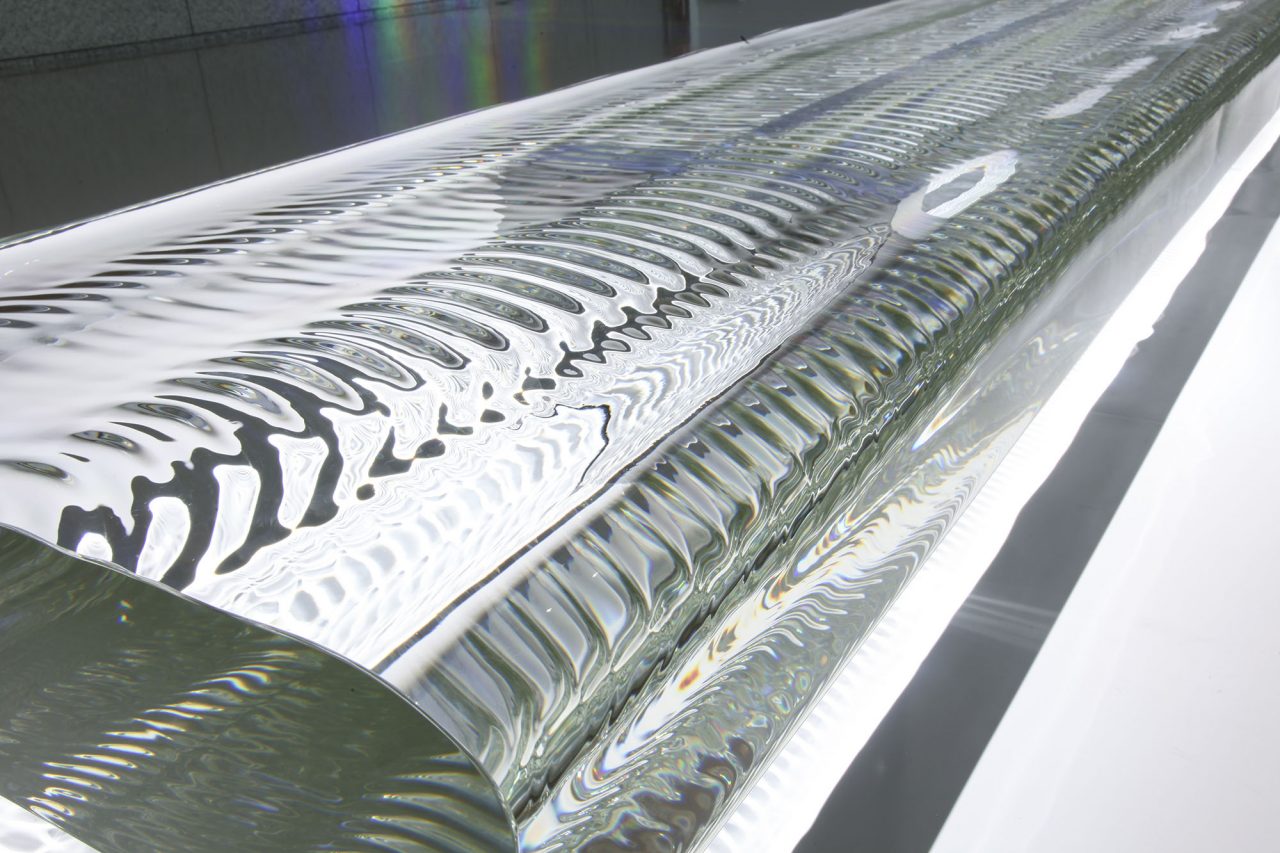

Japanese contemporary artist and designer Tokujin Yoshioka looks to the relationship between nature and human senses, producing works transcending boundaries within the design and art sphere, unconstrained by material or form. Renowned globally for his experimental creativity and experiential works, Tokujin looks closely at found occurrences and energy in nature, from optical reflections and refractions in light, to morphogenic processes in mineral crystal formation. This, then becomes the art itself.

How can one replicate the feeling of the softness of light or visualise particles of oxygen? Driven by a fascination of nature, Tokujin creates new relations to the world embedded with the fundamentals of way of design thinking, both with natural materials and new innovations in technology.

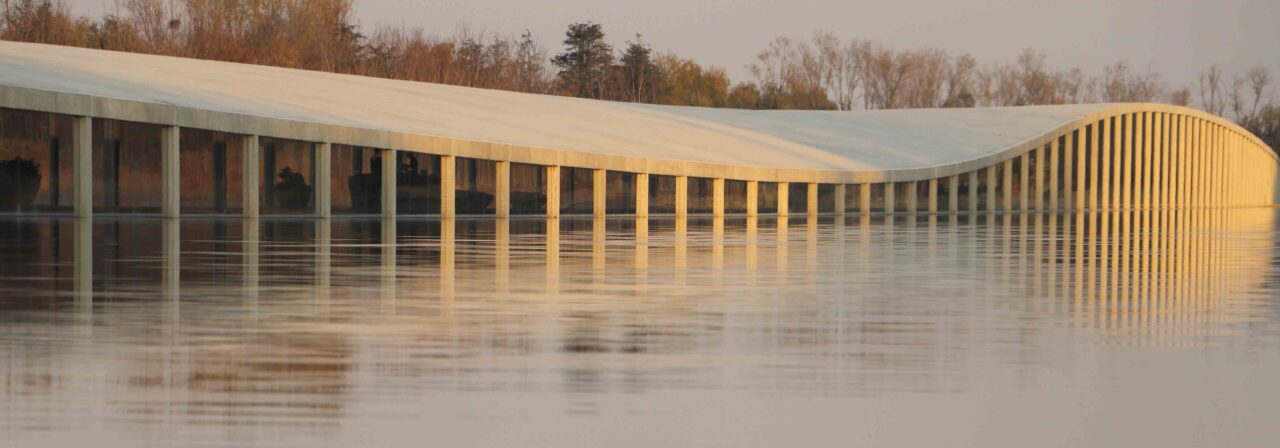

With work ranging from full-scale light installations with complex light prisms, to an all-glass traditionally-inspired yet contemporary Japanese glass tea house situated on a Kyoto mountaintop. Tokujin closely articulates the spontaneity of nature with a mindful exploration in materials from glass and brass, to paper and even “baked fiber” polyester elastomer.

After having studied and worked with revered Japanese designers Shiro Kuramata and Issey Miyake, Tokujin found himself continuing his ongoing and now 20-year-long collaborative work with Miyake whilst establishing his own artistic practice and design studio in 2000; now working with Louis Vuitton, Cartier, LG to name a few, whilst conducting solo exhibitions and exhibiting works at the Museum of Modern Art(MoMA) in New York, Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein, to the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOT) in Tokyo.

Constantly challenging perceptions of light and space, Tokujin continues his extraordinary investigation and correlation between nature, science and technology pushing boundaries in the disciplines themselves, making him of one Japan’s leading contemporary artists and designers of today. Visiting Tokujin at his studio in Tokyo, it was nothing short of special. Found in the small backstreets of Daikanyama, his studio is located in a 150 year-old converted rice warehouse with an added concrete entrance, designed by Tokujin himself.

Joanna Kawecki: How do you usually start your day?

Tokujin Yoshioka: I start my day around 6am with a coffee and think about the things I have to do for the day.

When you were younger, was there a pivotal moment that inspired your interest in design and art?

When I was in Second Grade in Elementary School I used to draw insects, and you could say that was my first moment that I first became interested in these types of creations. There’s an insect called Koganemushi (Scarabaeid Beetle in English), and when I was younger I painted on top of the beetle. Later in Elementary School, I also started oil painting still life and basic objects.

When you were younger do you remember being particularly inspired by a design or product?

When I was in High School, I was really interested in fashion. At that time, when someone said ‘designer’ it usually meant fashion designer because around that time people didn’t really know there was a genre called product design. There was mainly car design, but nothing about product design, industrial design or any other design fields.

Do you have a particular approach to your design process?

There’s no rule or definite process that I have to follow. For example, when I receive a project offer and have the first meeting I sometimes come up with an idea during the meeting. Then, I think of possible ways to realise it, depending on the client and situation. My ideas come from what I am fascinated by.

You are also quite diverse in the materials you use, from glass to brass to crystal. How do select or seek materials you want to explore or work with?

There are various ways of approaching and finding materials. Sometimes I search for them and at other times I also invent the materials I’d like to work with. I always think about what I want to express, or what I or people would like to experience through the work, and to achieve that vision I try to find the right technology.

While you have your main studio in Daikanyama, how much do you outsource for your projects?

For example with glass, we work with 10 different companies, each with their own specialty. Some companies are best at cutting or shaping, and so we choose depending on the project. When I approach a production company, I already have a clear vision about what I want to make. I ask them if they can make it or not, and if needed, I continue to look for another craftsman or specialist.

When you are working with traditional factories, are they usually familiar with contemporary design?

Working with a company who doesn’t know about design, it has a possibility of making something interesting. With my brass bench at Kinkakuji in Kyoto, we worked with a company who usually makes buddha statues from brass, and this was the first time they made a bench design in brass. As they are technicians and craftsmen they didn’t really view it as new or if it already existed, instead their viewpoint was just if it was possible to make with their technique.

I’m very interested in the mixture of design and art.

It will be a strong message if I can introduce a design that no-one has seen before.

Do you think it is a designers role to be able to push these companies to explore their own technology?

The most important point is to discover what the company’s mission or concept is. Then, I reinterpret their vision through my design.

As a designer, you bring an artistic vision to a company who are more technical. But you are seeing it as an outsider who can give it more go a humanistic value.

Yes, as an outsider I can see the brand with an objective vision and try to focus on the good or interesting side of their technology or concept. I try to express the most valuable essence of the company and incorporate nature or a human sense into the creation.

For example, with my Maison Hermès Window Display, I thought of how I could show the scarves most beautifully. I really thought about it deeply and what I should show or express, looking at what is the most important essence.

Hermès actually have a gallery on the top floor of their store in Ginza. For a brand, the most important thing is their culture. If it is just for commercial purposes or products, then they don’t need artists, but I think the most important thing is the culture, so when working with brands I try to re-interpret their identity.

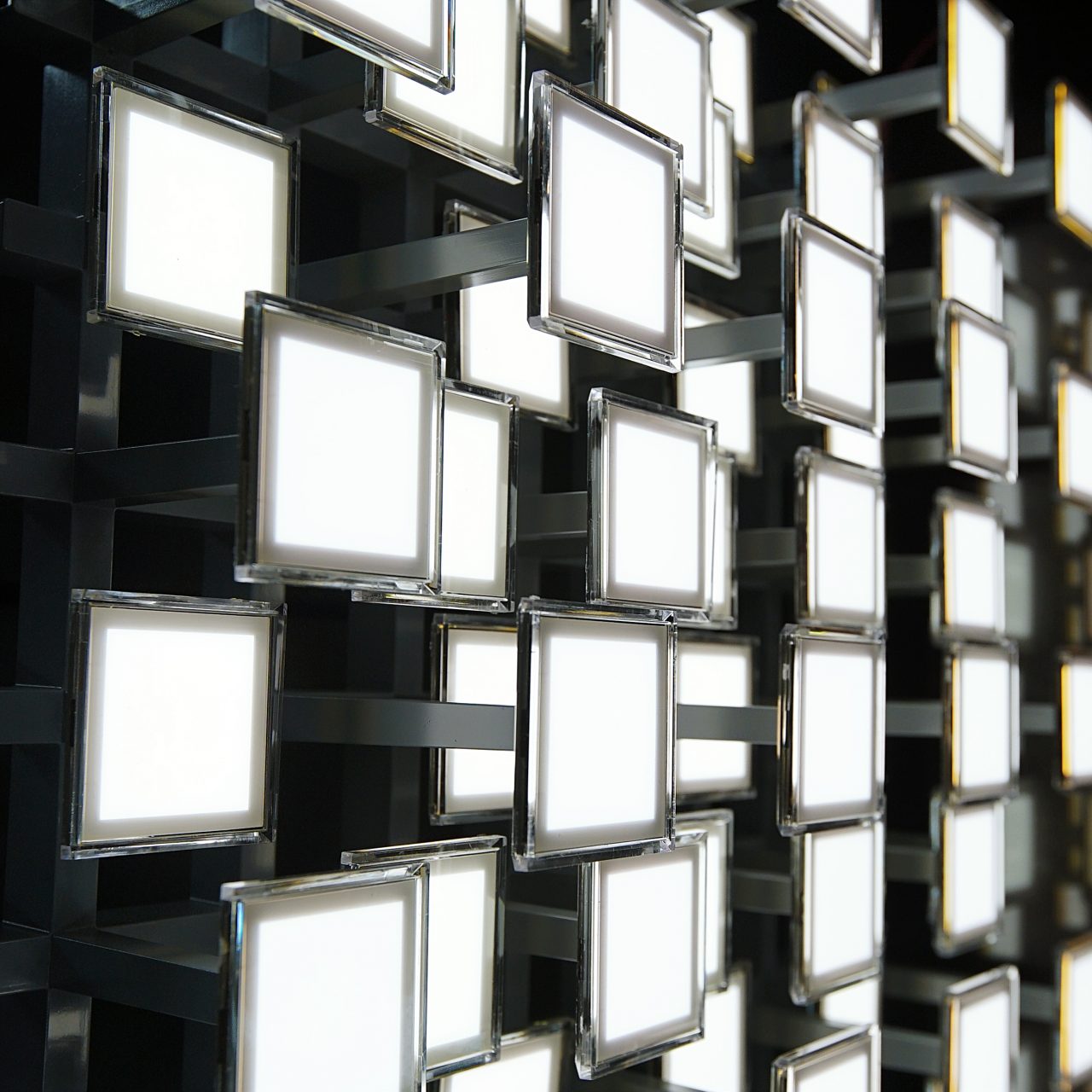

In Milan this year, you held an immersive large-scale light installation in collaboration with LG, titled ‘Tokujin Yoshioka x LG: S.F Senses of the Future’ utilising chairs embedded with LG’s organic light-emitting OLED displays. How did you come to work with their OLED lighting technology?

Firstly, I asked their technicians what type of technology of theirs that I could use for the work. I also asked how they could customise their technology or how far they could invest or push their technology for the project. To reach that design, I had many requests for the technicians. I asked about certain details, or how they could realise the double-sided signage.

Now there is a growing staple of design galleries globally alongside art-specific galleries. How do you define what is art and design to you?

There are a few design galleries in Europe, but my creations are not for making limited editions and the purpose for my work is not about selling. I simply create for what I want to create. Eventually it may have its own edition later, and that is also fine.

You are working with a sense of nature, and exploring light. Do you choose the materials you want to work with with a sense of responsibility as a designer to introduce ethical or conscious materials?

I like genuine materials. For example; paper, glass, metal or something that was not created by imitating something else, and that was created by a pure material. Of course, sometimes I have to use artificial materials, or sometimes when I want to create or realise something then I have to choose the material that is produced artificially, but I always thinks the important thing is that it has a genuine or pure feel as a true form.

To make my idea or design strong or impressive, I sometimes have to start my thinking process from the material, what kind of material to use. Most designers explore forms or shape of objects, but I think that the fundamental thing about designing, is the way of thinking of design and not just the superficial form or shape.

Has this deep thinking come from previously working with Shiro Kuramata and Issey Miyake?

They are very open-minded and also powerful about creation. They influenced me a lot. What I learned from them, is that design can be free. Design is about freedom. Like nature and plants growing. Some designers are stuck with what is a conventional design or idea, but Kuramata-san and Issey-san are very free about ideas and design.

Japanese have a completely unique vocabulary to describe nature with words that reflect Japanese culture and aesthetics such as komorebi (sunlight that filters through trees) Do you think being Japanese has a strong influence with your work and relation to nature?

I do think that Japanese people understand and recognise nature in a different way. For example, we see Gods and spirits in every natural thing, such as our belief that there is a spirit even in a mountain.

No design is comparable with nature. To you, what is the most fascinating or complex design from nature?

Sunlight. The energy of the sunlight, and the effect of the light in relation to other elements of the sky. It is not just about the bright side of the light itself, but the light can create shadows in the darkness. I’m more fascinated by the strength or the energy of nature, rather than the beautiful side of nature. I also like waterfalls and really love the The Rhine Falls located in between Switzerland and France.

Is there anything else you’d like to explore this year or in the future with your work?

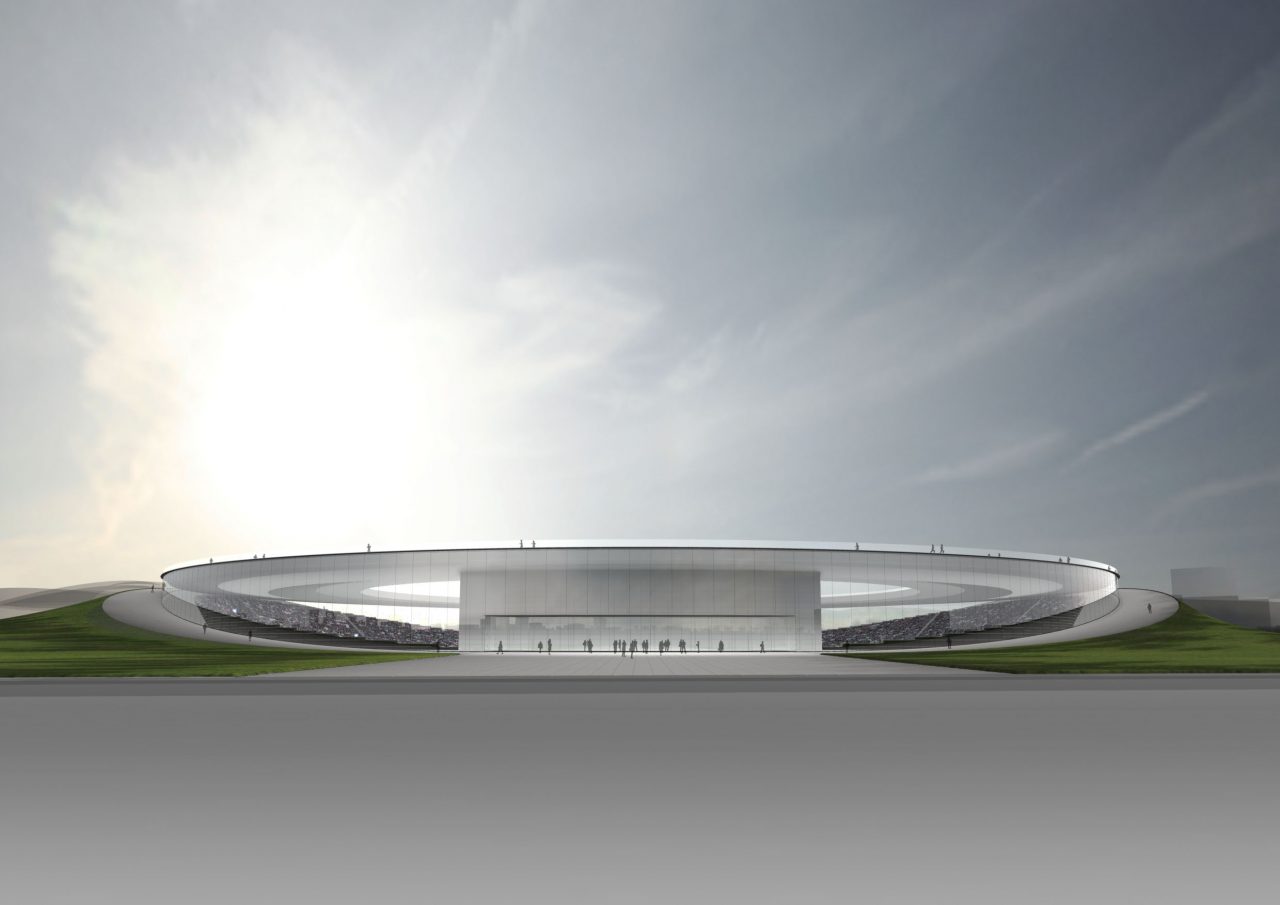

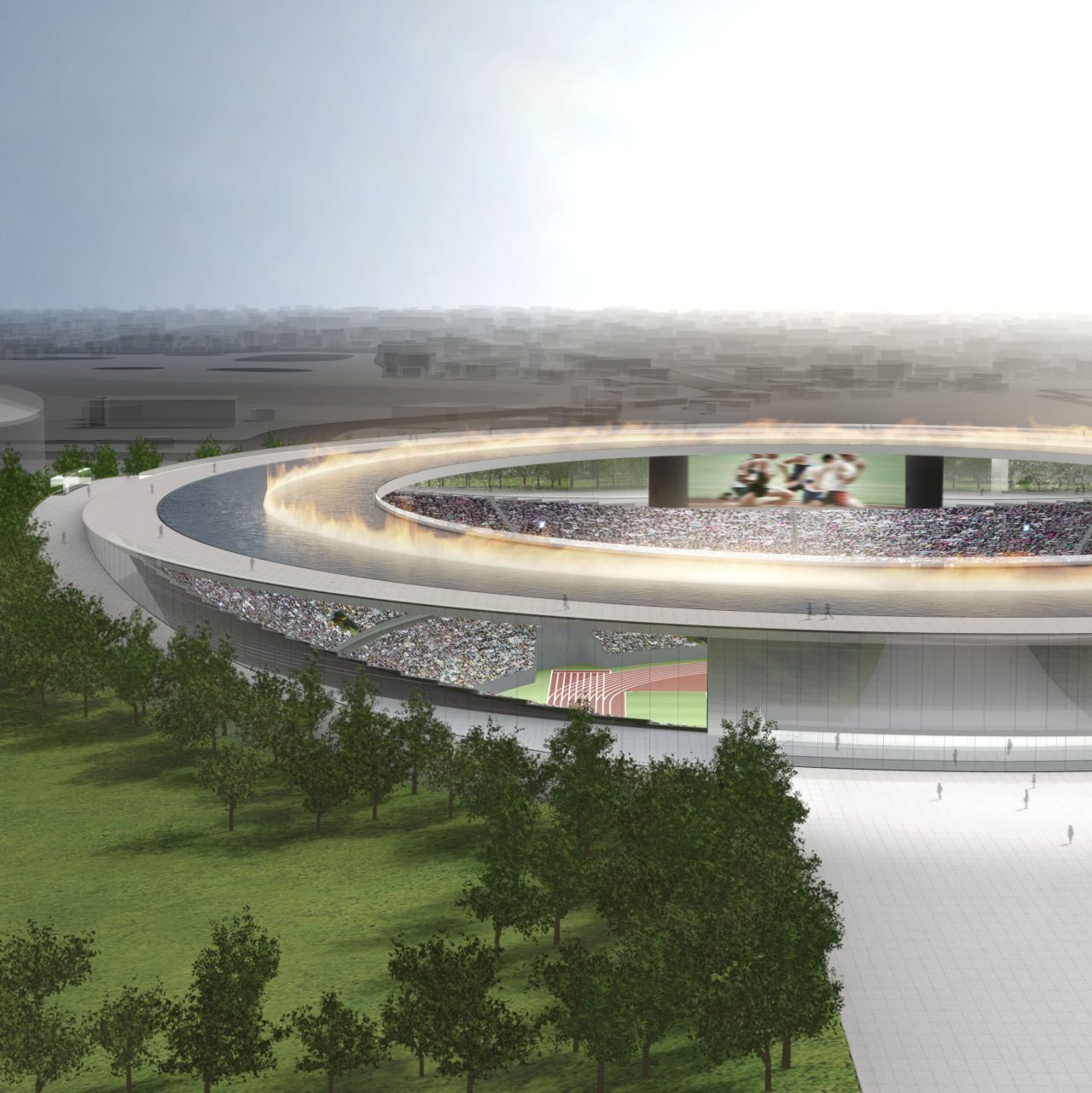

I’m interested do something for the upcoming Olympic Games in 2020.

Speaking of which, may I ask why you re-envisioned and created a new potential designed the ‘Floating Fountain’ for The Olympic Stadium after the Zaha Hadid design was rejected?

It was my wish that this idea will live on perpetually and realised somewhere in the world in the future. I hope the rejuvenated New National Stadium will become a symbol of Japan as a sacred site for athletes from every corner of the earth.