FUMIE SHIBATA

Design Driven By Humility & Humanity | We Visit The Tokyo Studio Of The Leading Japanese Designer

Often the best designs are those you don’t notice at all.

Great design surrounds us as a brilliant combination of form and function, perfectly aligning into your daily routine — almost as if it had always existed. These designs prove to be the most long-lasting to stand the test of time as they go beyond the physicality of an object, and instead assist in human connections, emotions and the journey of life. This is perhaps the best way to describe the work of leading Japanese designer Fumie Shibata who crosses product, furniture and industrial design, creating some of the most unassuming, yet important designs found in Japan today.

“No matter what I’m going to design, I already have prior knowledge about it,” explains designer Fumie Shibata. “Perhaps I’ve used or seen it before, so I have experience with it as a user. The experience becomes an important hint when designing, and analyzing that experience objectively is the first part of the design process.” Shibata explains her design process driven by an inherent humility and understanding of the human condition— an approach that has become synonymous with designs and almost a signature for her in a way. It is from her own perspective of life, with empathy and a deep understanding of experience, behaviour and emotions that she embeds and directs her designs with.

With a small studio of five staff in a light-filled and spacious studio, we are greeted with a generous smile and a one-cup drip coffee in one of her glass mug designs. Through years of enjoying coffee at Blue Bottle cafes in Tokyo served in a perfected rounded glass mug, surprisingly solid yet delicate and fluid in form, it became apparent that it was a Shibata-designed cup for Japanese brand KINTO, as part of her Unitea series. Surprisingly, the unique glass design also accommodates hot beverages and is durable enough to withstand immense daily use. Sitting in her studio situated in Ebisu, we are surrounded by her designs ranging from furniture to lighting and seating. “It’s been a year and a half since we moved here to Ebisu,” she begins. “Before that, our office was in Roppongi, right in the middle of Tokyo. It was fun being in such an aggressive area, but we needed more space in the studio and decided to move here. It’s calm and comfortable compared to Roppongi, and the large trees right out front were the deciding factor. Tokyo is known for its many good restaurants, and Ebisu is one of the best areas to eat. Being able to look forward to eating lunch every day is a big plus.”

In Japan, many of Shibata’s designs are common daily items found in convenience stores, pharmacies and cafes. It is without a doubt that you may have even come across one of her designs yourself without knowing. From the 100% recyclable all-plastic umbrella found at 7-ELEVEN Convenience stores, to a MUJI bodysofa, to the new generation of Digital Vending Machines on JR train station platforms — her items are designed to fit comfortably within all aspects of daily use. A familiar and beloved design found within all Japanese households is the Omron digital thermometer, with an all-white exterior and curved silhouette that perfectly fits within ones hand. Shibata led the design focussed on “motherly love”. She explained, “In hospital, we trust our doctor. At home, it’s mother, her reassuring presence, her knack for knowing the right thing to do and, above all, her unconditional love.” Her human-based approach also shaped a democratic form; from increasing the size of the LCD screen to creating an ambidextrous form, it allowed users of all ages and abilities to activate the simple functions.

Looking into Shibata’s creative lineage, it’s possible to link her family business in the textile industry as an influence on her interest in design and craftsmanship. “My family made textiles in a town at the foot of Mt. Fuji, so craftsmanship and creation was part of my everyday life growing up.” She continues, “The town where I was born [is known for its] textile work, so my family became involved in textiles from my grandfather’s generation. They originally made Koshu textiles, a local fabric. But the Japanese textile industry wasn’t doing well when I was a child, and my family transitioned to making fabric for European brands and lining for high-end fashion. My childhood memories are filled with things like the smell of dyes and the smooth feel of fabric.” She reflects on the indirect influence, “It’s not so much that a specific design inspired me to want to become a designer—rather, I studied design because I wanted to work in creating something.”

Where does one of Japan’s leading designers find daily inspiration for design? She details, “I don’t do anything special for research, but I think I’m picking up various things as I walk around town or visit exhibitions—interesting ways to express things, comfortable textures, etc. You can’t consider colour separately from material, so our usual process is to select the material first, then start planning colours.”

Of the projects I’m currently involved in, there isn’t a single one that doesn’t consider the environment.

Where does sustainability sit in the contemporary design dialogue? “Of the projects I’m currently involved in, there isn’t a single one that doesn’t consider the environment. When working to create things in this day and age, prioritising the environment is a requirement. For example, I’m working with a chemical company to propose a better way to use plastics from a designer’s point of view. Plastic is an excellent material, and it’s not intrinsically a bad thing—it’s just that the way it’s used and processed can be problematic. I don’t know if design can solve these issues, but it is possible for design to help people notice. Starting from something small to create a large movement is what design does, after all.”

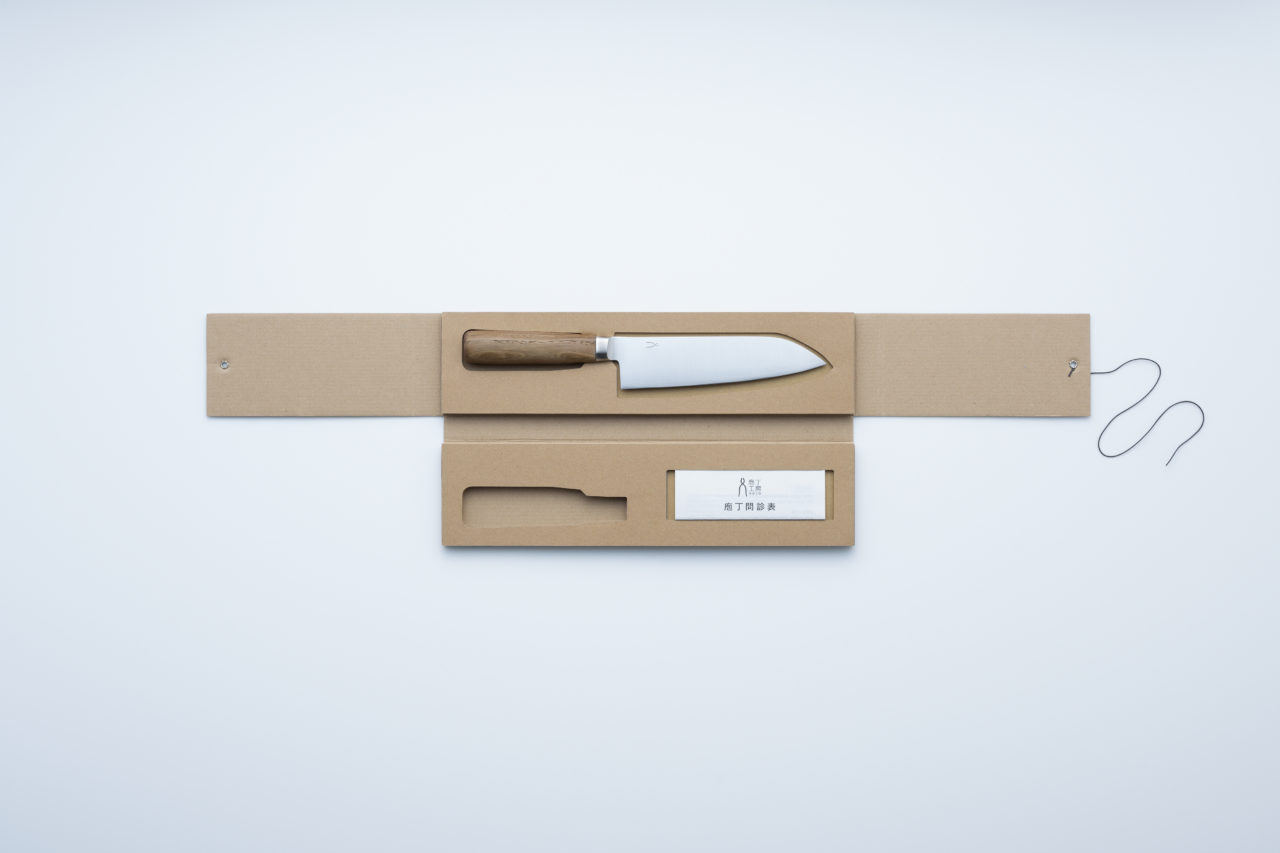

Her most recent design for Japanese paper distributor TAKEO took the media by storm — a stackable paper lid that offered a solution to dramatically reduce plastic use and consumption. “This is something I made for the 2006 Takeo Paper Show. The initial vision came from the feeling that a plastic lid was overdoing it, as well as a desire to do something about the hassle involved in separating the paper cup and plastic lid when throwing them away. There was less focus on the issue of plastic at the time, so the idea didn’t become an actual product. But as various brands began to address issues such as microplastics, there was renewed interest in the paper lid. People from the paper distributor Takeo and the paper cup manufacturer Dixie Japan took on the project at their own expense. Manufacturing paper cups requires significant capital investment, so we started by making paper lids that fit existing cup sizes. Dean & Deluca expressed interest in this approach, and they began test use of the lids. With this design, maintaining the same functionality as plastic lids isn’t important. The design’s approach is that you need both aroma and flavor to fully enjoy good coffee, and that a lid can be something simple that’s only necessary when carrying the cup around. I’d like to see people in stores making the choice to ask for cups with or without lids depending on their needs. I wanted to propose a method that was as simple as possible and could be used only when necessary.”

I’d like to see people in stores making the choice to ask for cups with or without lids depending on their needs. I wanted to propose a method that was as simple as possible and could be used only when necessary.

In the presence of Shibata, her wide-eyed perspective to design is incomparable. She notes one of her main design inspirations as: Eiko Ishioka, the extraordinary design provocateur whose undefinable work crossed costume design, visual design and art direction in film, advertising and print media — most notably known for her work in Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula. Referencing the undefinable Ishioka perfectly reflects Shibata’s own perspective on design. As she mentions fellow Tokyo designers and architects, she speaks with a camaraderie and sense of community that reflects her own humility and humble nature. As a leading figure in Japanese design, her noncompetitiveness is refreshing and an invaluable influence on the industry at large. Whilst she presides over the Department of Science at Musashino Art University, she notes fellow colleague Kenya Hara, another of Japan’s most renowned designers. At the university, Shibata’s particularly unique course is differentiated to all other classes, due to her science and philosophy-focussed approach that introduces new values to the diversity of design — what it is, and can be. “I think there are things that aren’t recognized as design yet that might be seen as “design” by the time the students are out there working on the front lines of design. I’d like to see them become designers who create new values, functions, and roles for design.”

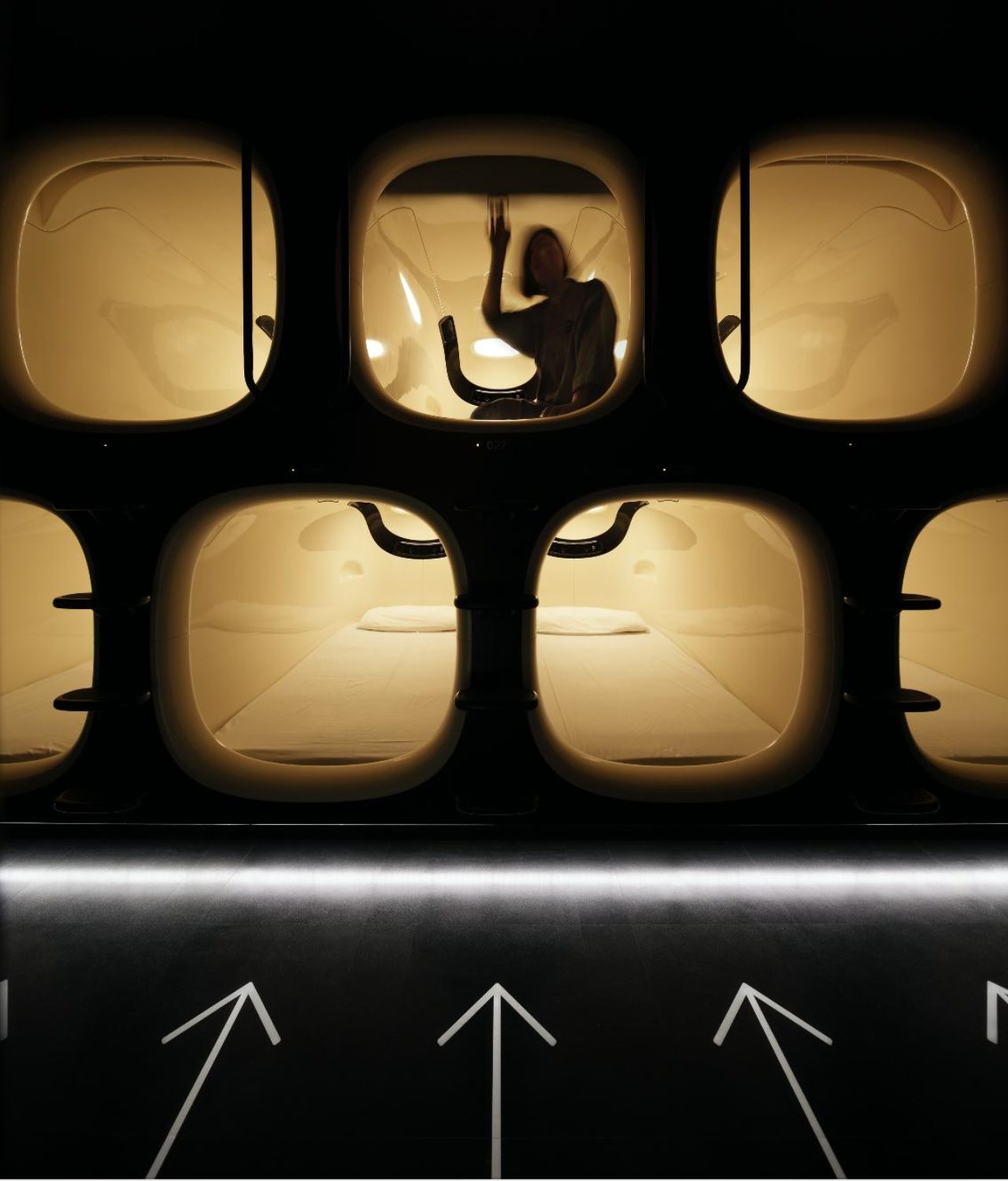

Her thoughts on the responsibility of a designer is met with optimism and self-realisation. “Rather than convenience or novelty, I think [what a designer must always value] is the pursuit of true enrichment and fulfilment—challenging ourselves to find ways to help people be themselves.” Take for instance Shibata’s direction for Japan’s nine hours capsule hotels, a revolutionary new travel offering for the youth led by flexibility and contemporary amenities. Comfortable, modern and embedded with furniture design and lighting from her fellow peers in design, her approach is greater than the concept itself, and set to influence a whole new generation of travellers and visitors to the country.

For a designer who has touched on all industries, its almost impossible to think of an industry she hasn’t reached. “I would like to try designing public mobility—trams, trains, etc. I would also like to experience the creation process somewhere other than Japan. When I worked with a glassmaker in the Czech Republic to make lighting, and I enjoyed learning the thought processes rooted in the local area and their culture of craftsmanship. Something that’s part of everyday life, like furniture design, is another one. There are still so many things I’d like to try.”

Rather than convenience or novelty, [what a designer must always value] is the pursuit of true enrichment and fulfilment — challenging ourselves to find ways to help people be themselves.