THOMAS J PRICE

Staying True To His Message, The Tipping Point For London's Most Urgent Sculptor Is Here

“Context is everything” explains artist Thomas J Price as we explore his recent works one Monday morning in his South London studio. Price, a multi-disciplinary artist working across the mediums of sculpture, film, photography and performance, is London born and based. His very individual work explores representation in its many forms – in addition to subconscious perceptions embedded into the human psyche – and presents them in utterly obvious yet completely unassuming ways. His sculptures, found in the city’s central business district currently, are like a Trojan Horse to the message he has been conveying for years: equal representation.

From studying at the renowned art school Camberwell, to attending the prestigious Chelsea College of Art and then the incomparable Royal College of Art Sculpture School where he received an MA, Price has stated that he actively sought the best art schools to learn and exchange thought with the best tutors and future contemporaries, because although born and raised in London, he was aware of his economic surroundings and status. Price’s trajectory has been swift, with his path an accumulation of his conscious decisions. It’s important to note that Price has held selected solo exhibitions at the National Portrait Gallery in London, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, Harewood House and Hales Gallery. Renowned British artist Damian Hirst holds his work in his own personal Murderme art collection, and Price’s works can also be found in the Rennie Collection in Canada. It’s no mean feat for an artist in their early 30s.

Born to a British mother and Jamaican father, Price has been working creatively from a young age. Encouraged by his mother who also studied at the Royal College of Art, he was able to express himself with the freedom to create in their family home. At 37 years of age the artist suggests he has been at it for a while, but in truth, he is just getting started. Price has been refining his skills, process and voice ever since, and the output is only getting sharper.

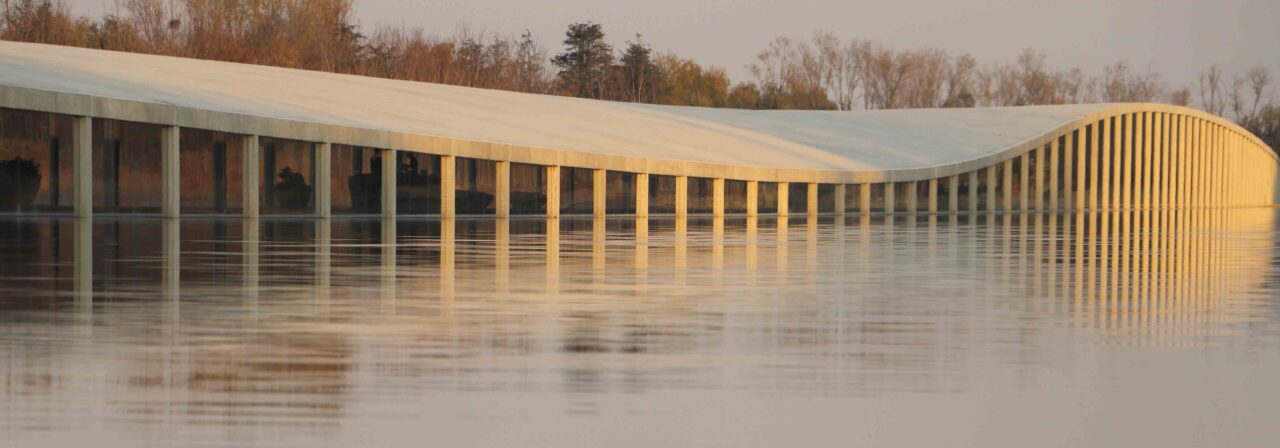

Ambitious, determined and focussed, Price has recently found a fitting platform in the form of the public sculpture realm. Through a major recent commission by Sculpture In The City (an annual public art event) this year, Price’s work found a fitting platform. Unknowingly it is a helpful step toward his message reaching a wider audience. Not only museum-goers, but to the general public. He’s amongst great company, with commissioned works for the public art event also by renowned British artists Sarah Lucas and Sean Scully in the mix. We first came across Price’s work unknowingly in a public park in Bow. Standing at 9 foot tall, we thought Price’s Network sculpture was a stationary individual from a distance. Upon closer inspection, we found the giant individual to be a sculpture – holding an iPhone and wearing a black puffer jacket – entirely cast in bronze, extremely well-detailed. It’s this type of surprise that public sculpture can convey, inciting unexpected emotion, and at it’s best, challenging perception. Price’s sculpture completely evoked our curiosity and we were eventually led to his work displayed on the Hales Gallery platform, whom he is represented by. This year Hales embarks on opening a New York gallery, with Price also moving there in late 2018 on his own accord. Next year in June 2019, Price will preset a major solo show in Toronto, Canada. Things are moving, and the pace is picking up dramatically. Price is gaining a new momentum.

Along with New York-based photographer VisualsByPierre, we discover more than bargained for in Price’s Acme-run studio in South London’s Deptford, one of the last Zone 2 areas yet to be fully gentrified (it’s part of a network of affordable art studios, a rare handful in the London city centre). Here we explore more about what the tools Price utilises for new processes and materials juxtaposed with the traditional, and the exciting new works he is currently working on. Amongst the clay, 3D-print machine and embargoed works-in-progress, we find out more about Price’s upbringing, evolution in the art industry and where he foresees to manifest his career furthermore.

ALA CHAMP: Your sculptures represent the different faces in society, and your work crosses many different mediums. Can you tell us more about your work with certain materials and their process?

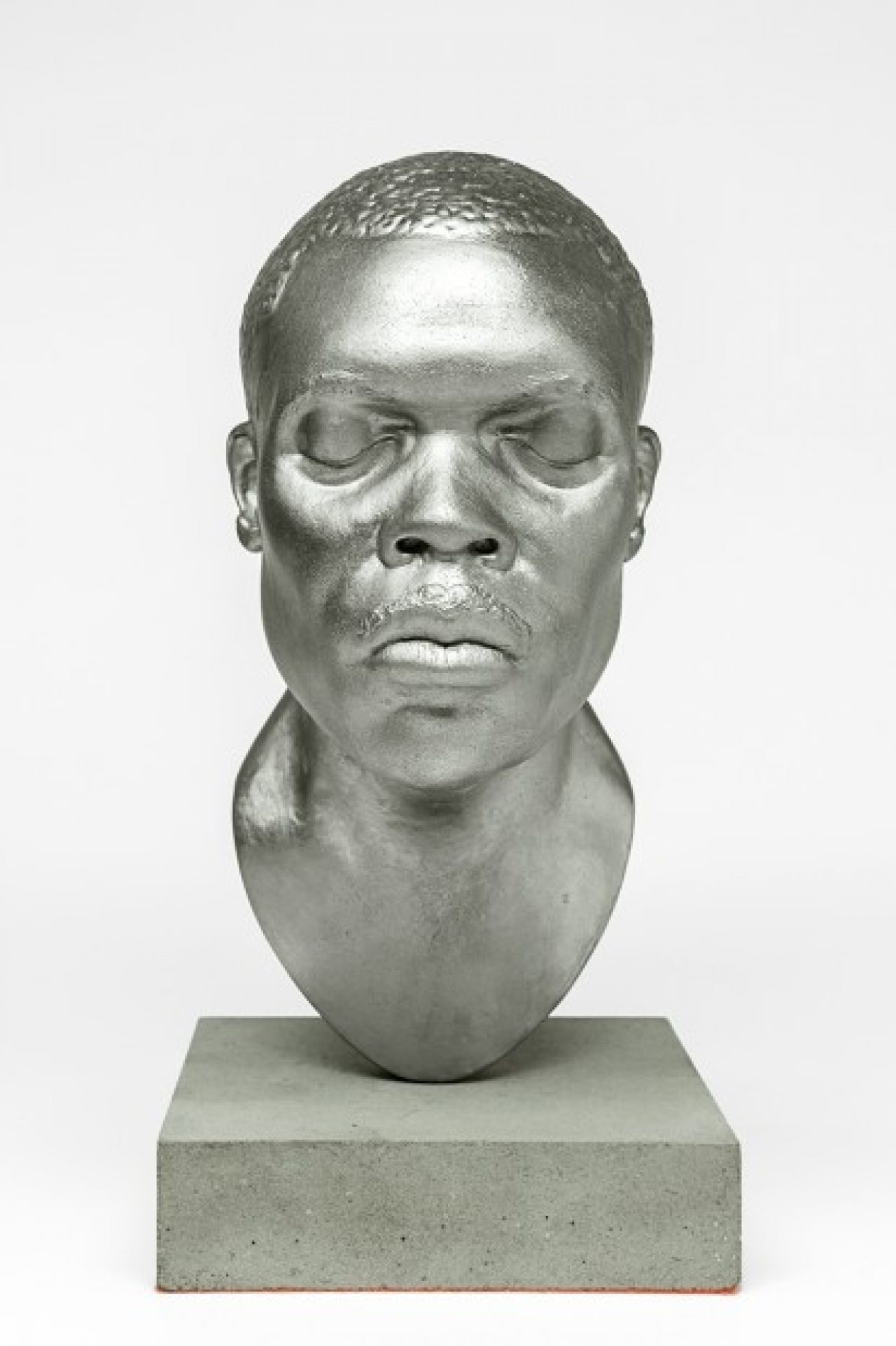

THOMAS J PRICE: The first sculpture I made was whilst I was in school at the Royal College of Art. It was presented on a shelf placed very low on the wall with one screw. It was a critique of monumentalism, saying that this sculpture with cheap materials, has as much prominence, status and intrinsic power as a large bronze. Gold-plated this, cashmere this, it is always attached to affluence. It caused bit of a fuss. Viewers were confused about ‘this head’, and although back then Gormley was doing it, it wasn’t in vogue at all.

When I did start to use bronze, I explored the subliminal message it holds. It lasts forever, and it is the material to make something ‘official’. It shows worth, and is essentially tied into the Greek Empire. Where some think real civilisation – ‘real civilisation’ – began, which is what I think is always very interesting also.

I never wanted to be in the portrait society. I’m just using this form, because it carries a message in a way that I’ve got sort of an iceberg, I do lots of different bits, I do photography, other types of sculpture, bits of drawing, and they sort of hold this tip of work above the water. They back it all up. Sometimes the iceberg rotates and something else comes up to the surface.

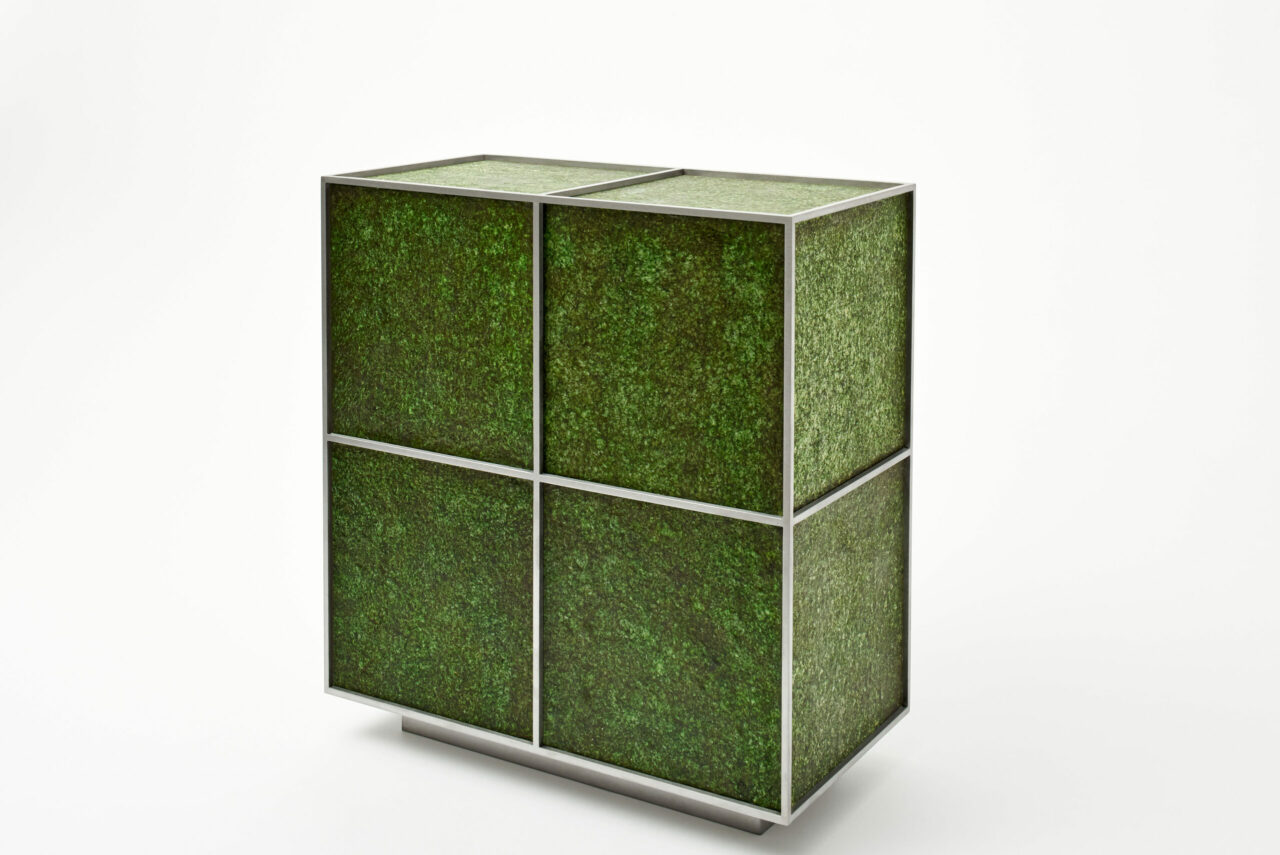

I’ve always wanted to play with the hierarchy of materials. I’ll use clay, paster, bronze, and make it look like plastic. I’ll use composites, such as aluminium composites and gold-leaf them, or leaf them in palladium. So I’m mixing up different techniques from different eras. Contemporary techniques with ancient materials and vice versa.

With the Network sculpture in Sculpture In The City at the moment, it is cast in aluminium, a material now used in computers, planes and various tech gadgets, but I’ve used the lost-wax process, first used thousands of years ago. It is about democratising the production process. That’s why I like 3D printing and playing around with those tools. So, there’s so much to do, and get involved with!

Just recently you were invited to be a part of a group show at the Stephen Friedman Gallery. Titled ‘Talisman In The Age of Difference’ it was curated by renowned British artist Yinka Shonibare and featured a stellar amount of pivotal artists all voicing a similar message in their works, can you tell us more about this?

I follow Yinka’s work, and he is a really important artist globally, so when someone from the gallery emailed me it was a great surprise. I saw the list of artists that they wanted, I thought ‘oh my goodness, that’s incredible’, as they are really important artists, and they’re also my contemporaries.

It’s interesting that we’re all plugging away at the same ideas, chipping away at what’s happened in society. To be in a group show with those artists, [it’s] a very happy moment. Stephen Friedman gallery represent really great artists, and I’m represented by Hales Gallery already, so it’s great for them to be open to it, because it is the context. I keep saying, context is king! Context is everything.

To be in that context, it just seems to really have slotted into a moment that I can feel with my work that things are really gathering momentum. I’ve done it for a while, but I started pretty early, things just seem to be coming together. With Sculpture in the City, the Talisman show, Frieze Sculpture last year and Frieze fair coming up in October. I feel so privileged to have these opportunities to actually engage with the public, and to start putting my narrative out there, as opposed to waiting for people to just see one piece at a small show. I feel like ‘oh, this is how it happens, you actually get to build your story and layer it. It’s a really interesting moment, it just requires a hell of a lot more work from me, to perhaps to do the work level of a more successful artist, without their budget! It’s one of these times where I might look back and think this is the point where things really…

…the tipping point?

Yeah, I hope so. Just for the sense that I have so many works I want to make, and it’s just getting those opportunities. Opportunities are starting to come along now, which is really exciting. It’s what I’m trying to do. As I’m getting older, I’m getting more self-aware with my work, so I’m facing up to the content. I’m doing it for a reason, otherwise there’s other things I could do. I’m obviously trying to engage with particular narratives, particular issues that I feel are important. So to have the opportunity to do that on a bigger stage is really good.

Is it also due to a timing in society also? Your message has stayed the same since the beginning, I’m wondering why it is only gaining momentum now?

Yes, I mean I’ve been trying to say the same thing and just waiting for people to listen. When I first started sculpting heads, it’s because I started sculpting abstract works, video works with unconscious narratives. It’s actually how perception unfolds, and how our narrative is made. Things we hear, things we’re told, our different attitudes and how they basically dictate how we then construct narrative for someone else. So I was working on the idea of empathy, and how we implant an understanding of a particular person, to a viewer. The human face is such a powerful tool of communication, you have an immediate response.

That was one key factor. I also wanted this work to feel accessible, not tucked under some art school grits, on purpose. I come from a family that didn’t have the contacts, so I knew that in order to get the right exposure I’d have to go to the right places: to get the right networks but to also get the right teaching and contemporaries so I could talk to people, have discussions.

I’ve been trying to say the same thing, and I have seen a difference with the response as I’ve been attached to more high-profile things. Now I’m not a student, that was the first milestone, [now] group shows, solo shows, building a narrative. Before people didn’t have a reference.

In regard to the timing in society, there are definitely interesting things happening. One thing I think is that black people have a greater expectation of engagement now, which is built upon the triumphs of previous generations (see the Soul of a Nation exhibition), who have always tried to champion talk about the important issues, and it feels like there is a real self-led confidence by this generation now. There’s that engagement where my generation and younger, are becoming aware of the histories of the struggle, but also the history of the wealth, the richness – all the different conversations people were having, but weren’t being heard.

Born in London, has this helped you establish yourself as an artist here much quicker? Can you also tell us more about your background? Did your family or geographical location influence your career path or perspective on life?

I understood at a young age that my mother’s abilities were not necessarily having an impact on her social standing, that was to do with money and to do with a certain confidence, self-belief and sense of entitlement. I could see that very clearly. She studied textiles at the Royal College, and we grew up in a very creative household. Instead of watching TV, we would make things. Expressing yourself. I didn’t realise until much later, that a lot of people don’t have that. I was able to turn my living room floor into studio. Regardless of money, it was a huge advantage. To have the encouragement and freedom to become comfortable with that part of the brain instead of locking it off and finding the shortest way from A to B – with B being money.

With my studies, I’ve done all the art school, from understanding articulation of forms to the bread and butter of critical thinking. In terms of work, you can sit in your safe art box, get the accolades. There is a need existing however for change, a big responsibility, and what if you could engage with people. There are a whole group of people that don’t feel represented.

Which is why I use figurative-looking things. In my mind they’re all abstract, they’re all made up people, experiments in physiognomy. People see them in the street, so that’s why I’m so excited in the way where my work’s going, it is a public display. It’s becoming increasingly important for my practise, to engage with people outside. Public sculpture has often been a victim of ‘design-by-committee’, and I’ve had work that’s been turned down.

In regard to my location, Frank Bowling for instance, fantastic abstract painter, basically had to leave the UK to try and get some sort of real response to his work. He moved to New York, where he still has a studio, and coming up he has a retrospective show at the Tate. I introduced him to Hales, as I was introduced to Frank by someone who contacted me about a project whilst I was doing a residency in Rome. I had tea with him and his wife Rachel, and when I saw his amazing works I was excited and angry, ‘why had I not seen these works before’? He was represented by a gallery, but they weren’t making the most out of what he was. He was a contemporary of Rothko, but completely overlooked. There is no getting away from the fact that he had been effected by racism at the time. Now he is having his emergence again, and he is in his late 80s.

I’ve begun to spend more time in the United States myself as the concepts in my work have a global vision, but really benefit from the subtle (and sometimes not so subtle) differences in experiences of race and class between nations. I’m having some extremely enlightening discussions in New York at the moment, and it’s been so interesting to see the Brooklyn Museum install of Soul of a Nation – originally exhibited at the Tate Modern, London – and talk to some of the artists about their experiences of making the works.

You’ve participated in numerous Frieze Sculpture exhibitions. What are you working on for the upcoming Frieze in October, or can you tell us bit about your next works?

I always work one foot in the moment, a toe in the future and maybe a hand in the past to steady myself. You’ve got to take in a lot, to create something with power, to create an effective piece of work.

At the moment, pieces lead to other pieces, and I’m working on what looks like much more of an abstract sculpture. A mid-size piece, working with textures, form and it’s sort of touching on elements of ‘what it means to be a sculptor’.

A sort of romanticised image of the sculptor in terms of surface marks, expression, expressive mark-making and working on that. Part of what I’ve been doing is to work with 3D software. But although it looks abstract, it is incredibly literal, it is a part of a figure. Of a clothed figure, and I’ve just taken a section of it. The word ‘section’ even made it in into the title, it was really important it was part of the title. So that will be presented at Frieze fair in October, and that will be the first time I’m showing that kind of work. Im really excited, it really ties into everything I’ve been working on, with the heads for instance, and it does it in a way that draws out different questions. It’s called Power Object (Section 1). It’s going to be on it’s side, in bronze on a base, like a relic. It ties into the idea of history, but also the shift in power.

∆

Interview | Monique Kawecki | Studio visit photography | VisualsbyPierre