THE GOLDEN LAND: JOAN DIDION’S PERSONAL GEOGRAPHY

Writer Magdalena Lane's Dedication to the Literary Innovator and Cultural Icon

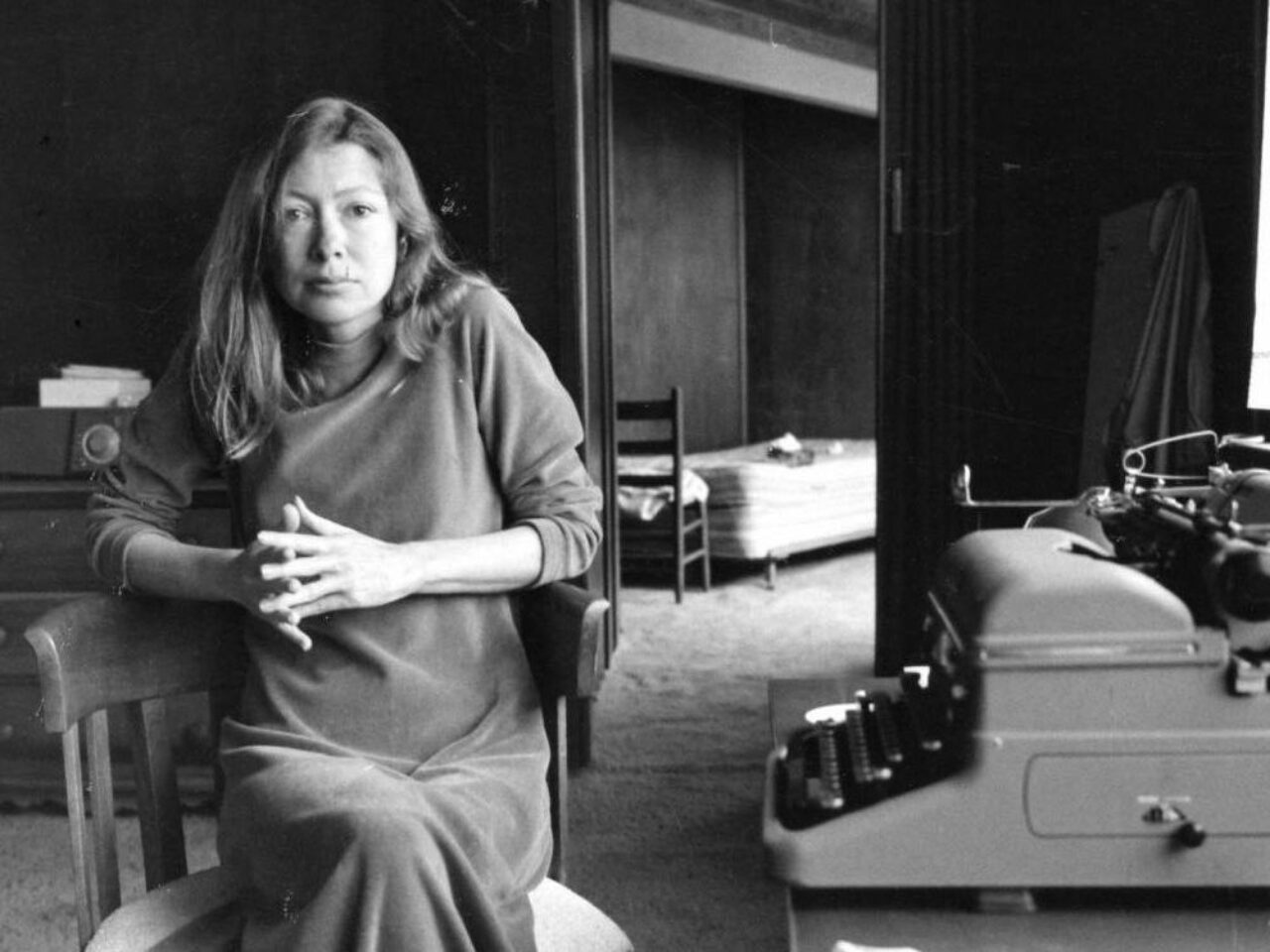

On 23 December 2021, American essayist and cultural icon Joan Didion passed away aged 87 of Parkinson’s disease at her home in Manhattan, New York.

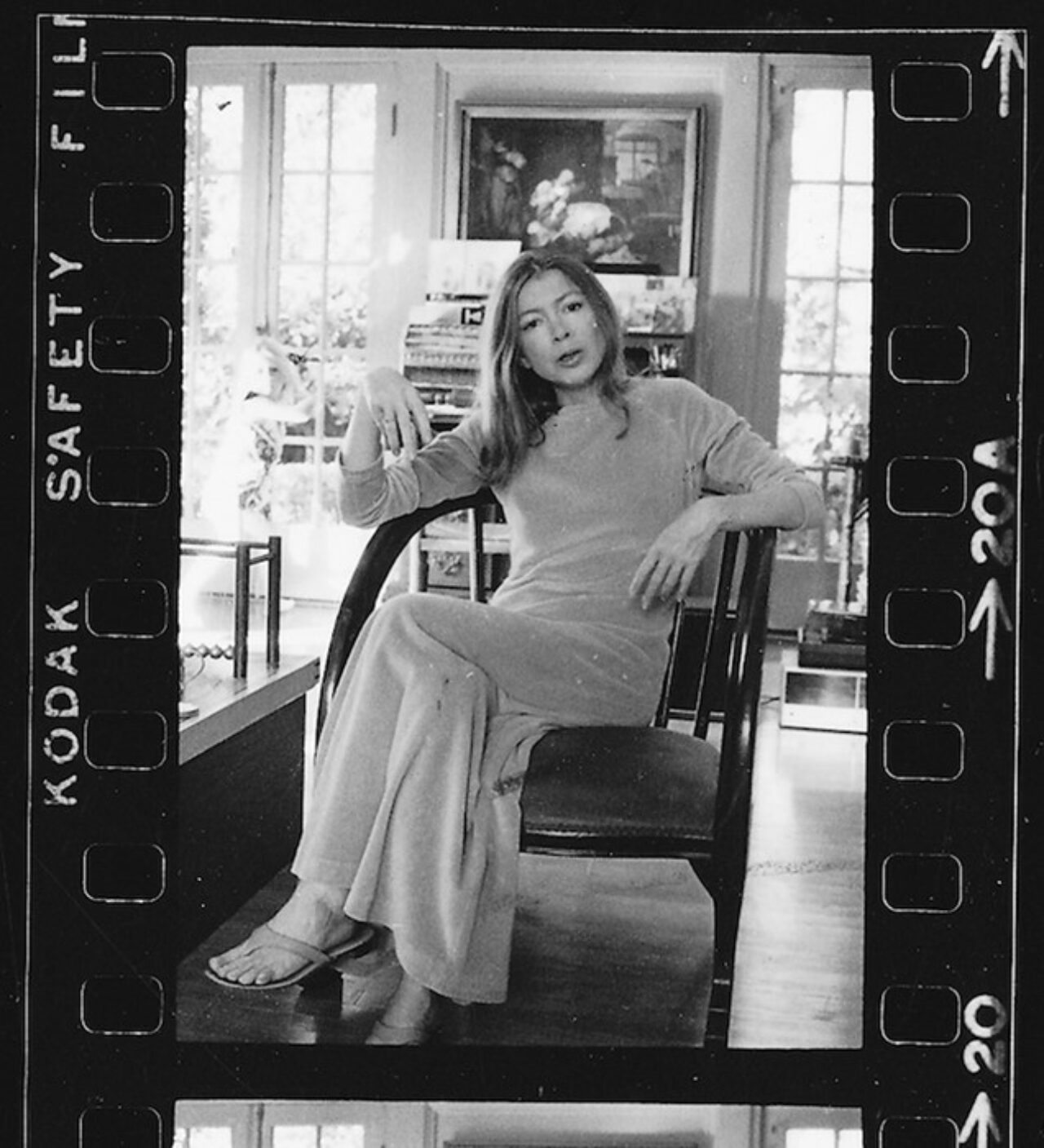

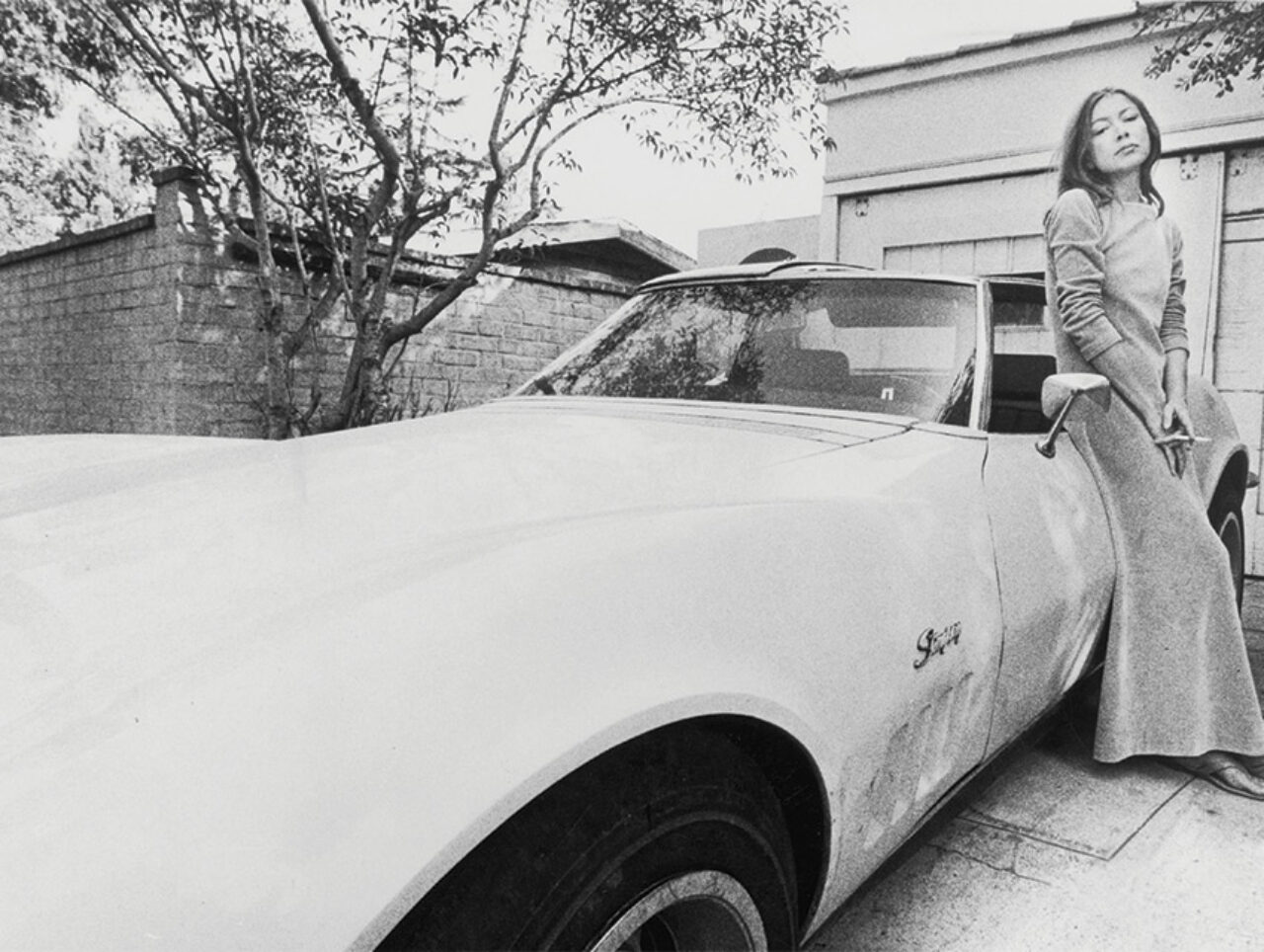

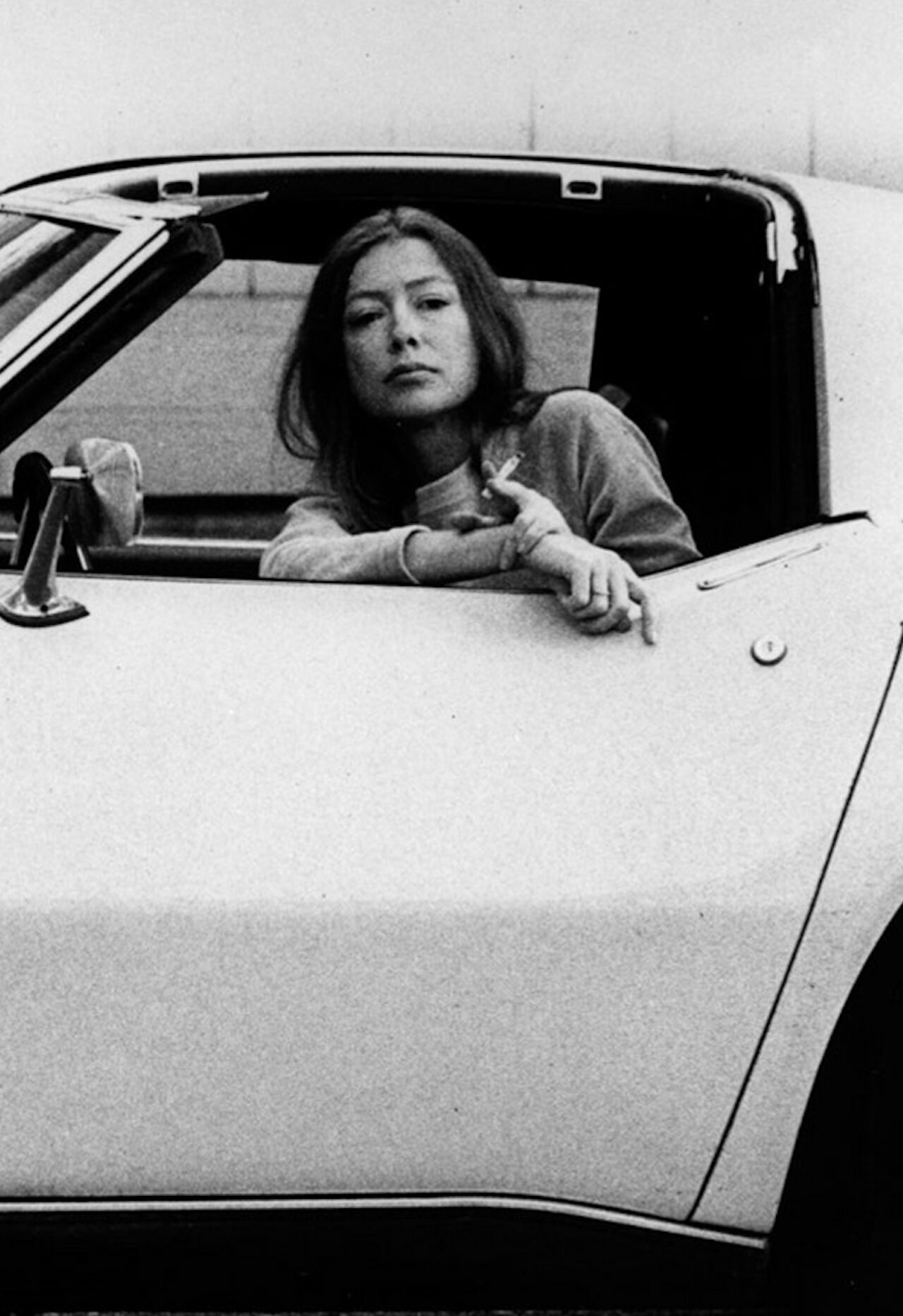

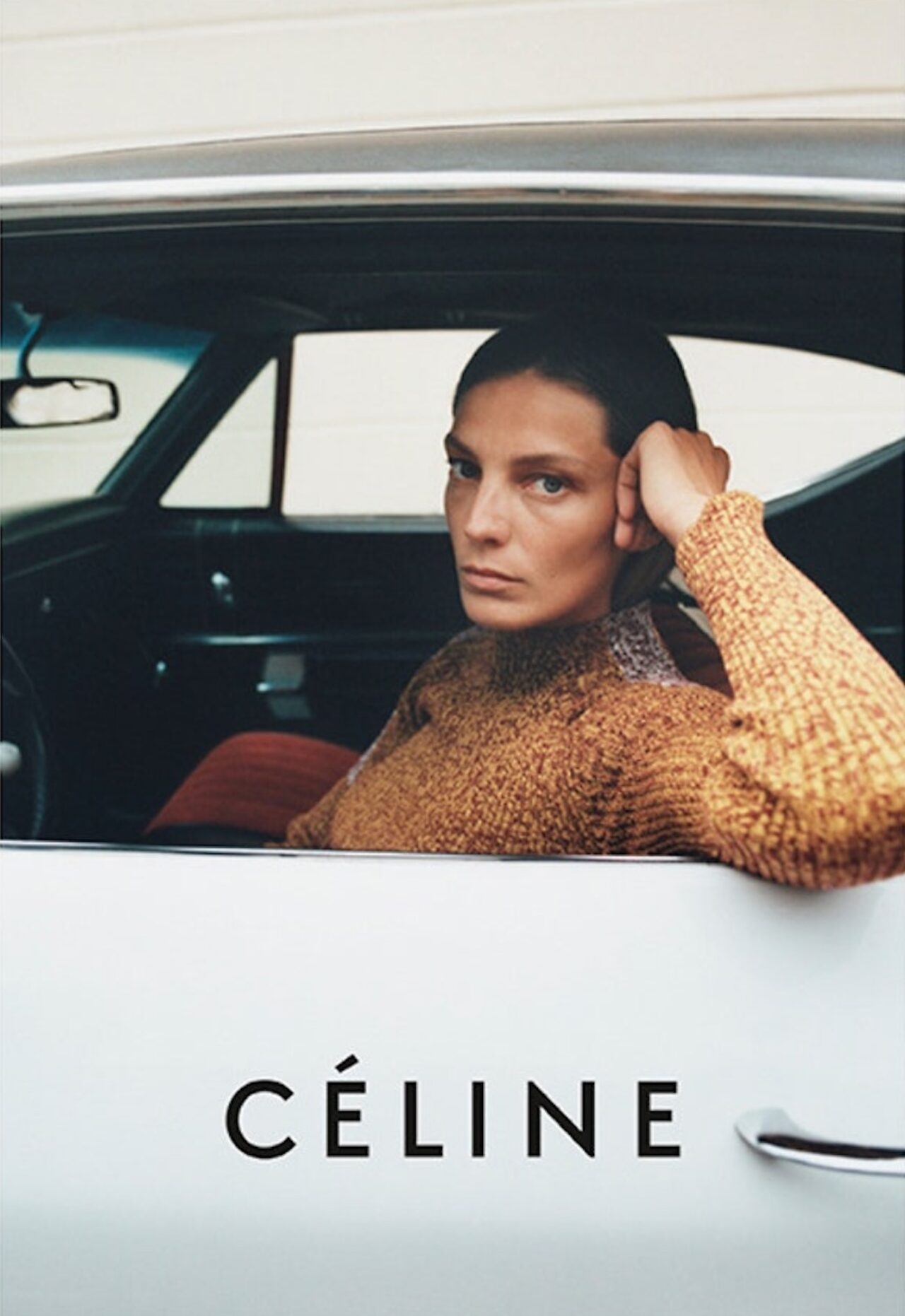

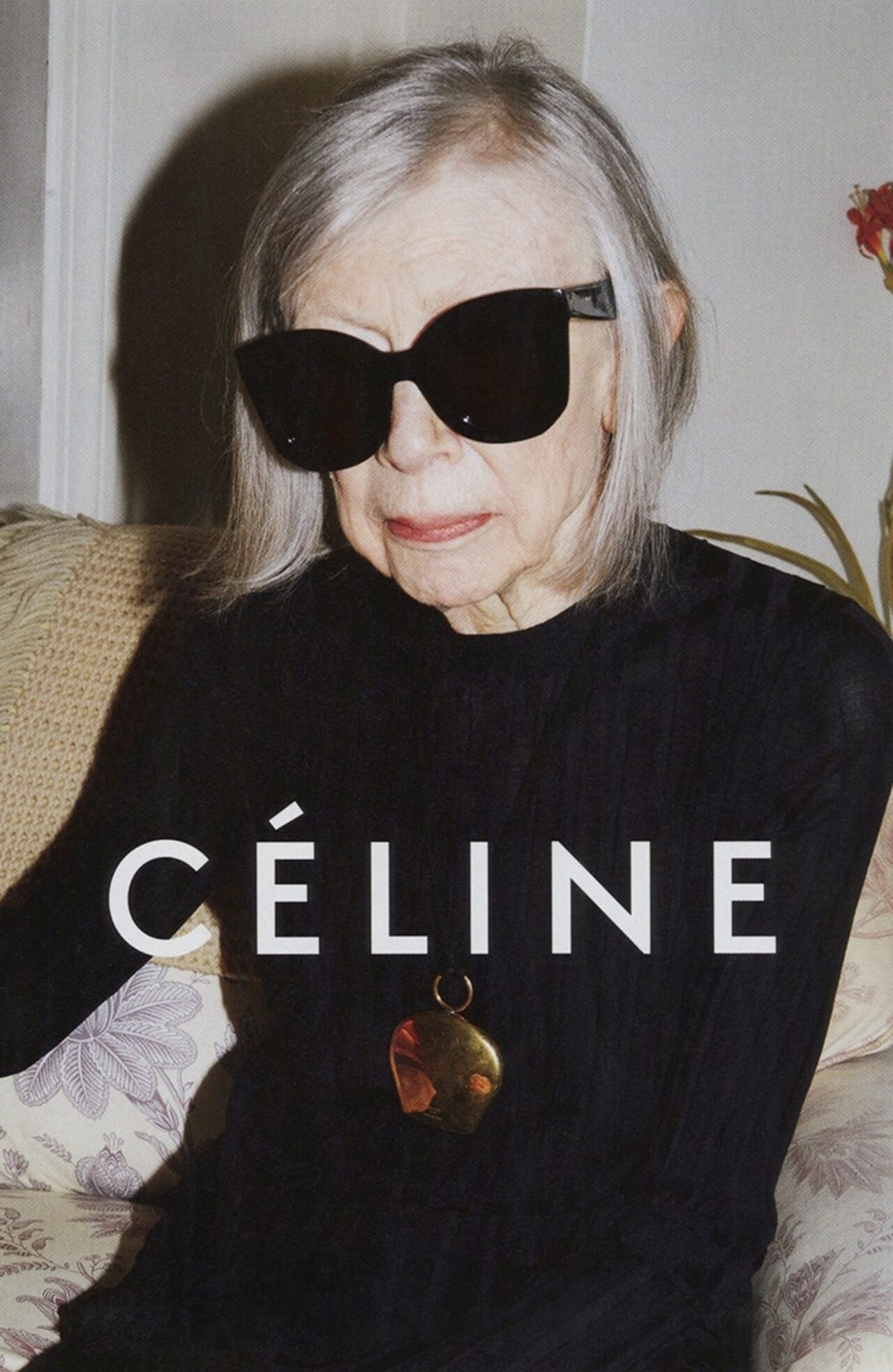

At 80, Didion was crowned campaign cover girl and muse for French fashion label Celine. Wearing her signature dark sunglasses, smooth hair shaped in a silver bob, her austere image epitomised the timeless aesthetic of the thinking woman. Style icon aside, Didion is most renowned for her significant literary innovation and collections of personal essays. Spanning six decades, she observed every major political and cultural moment in America. At the centre of this significant literary legacy lie her highly personal observations of California during the unprecedented and volatile American counterculture movement of the 1960s and 1970s.

California as we know it today, it’s iconography and place in our imagination, was shaped largely by Didion and her contemporaries.

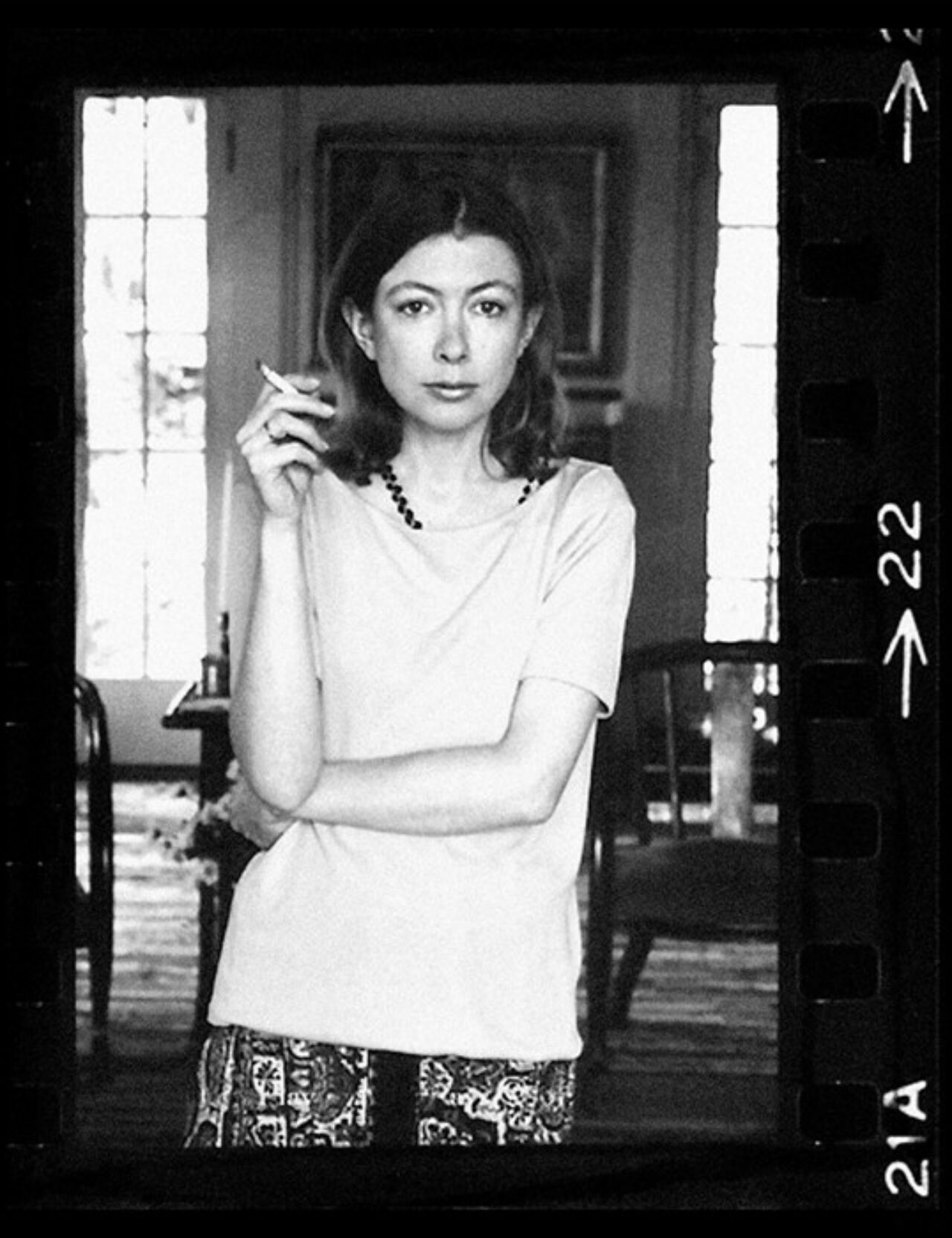

Didion was born in Sacramento, California and can trace her family lineage back to the pioneers who sought prosperity and gold when they crossed the plains to establish the Western frontier of America. Didion’s love for California brought an emotional integrity to her subject matter unmatched by her male literary peers of the time, such as Tom Wolfe and Hunter S Thompson. Seminal are her breakthrough and second collection of essays, Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968) and The White Album (1979).

Understanding California, (or any place) was for Didion, to understand the conceptual complexity of place. A vulnerable construct created through the dynamics of political power, economic attainment and often presented as utopian fantasy by mainstream media.

With emotional force, Didion invited readers to observe the gap between the Golden Land’s myth of prosperity, personal freedom and democracy and to consider instead what she found in the debris of 1960s California due to social fragmentation, lack of political vision and moral devastation.

‘Place belongs forever to whoever claims it hardest, remembers it most obsessively, wrenches it from itself, shapes it, renders it, loves it so radically that he remakes it in his image’

– Joan Didion, The White Album, 1979

With their rallies for peace, democratic slogans and music proclaiming love for all, the hippies leading the counterculture movement looked to be carrying California towards a bright future.

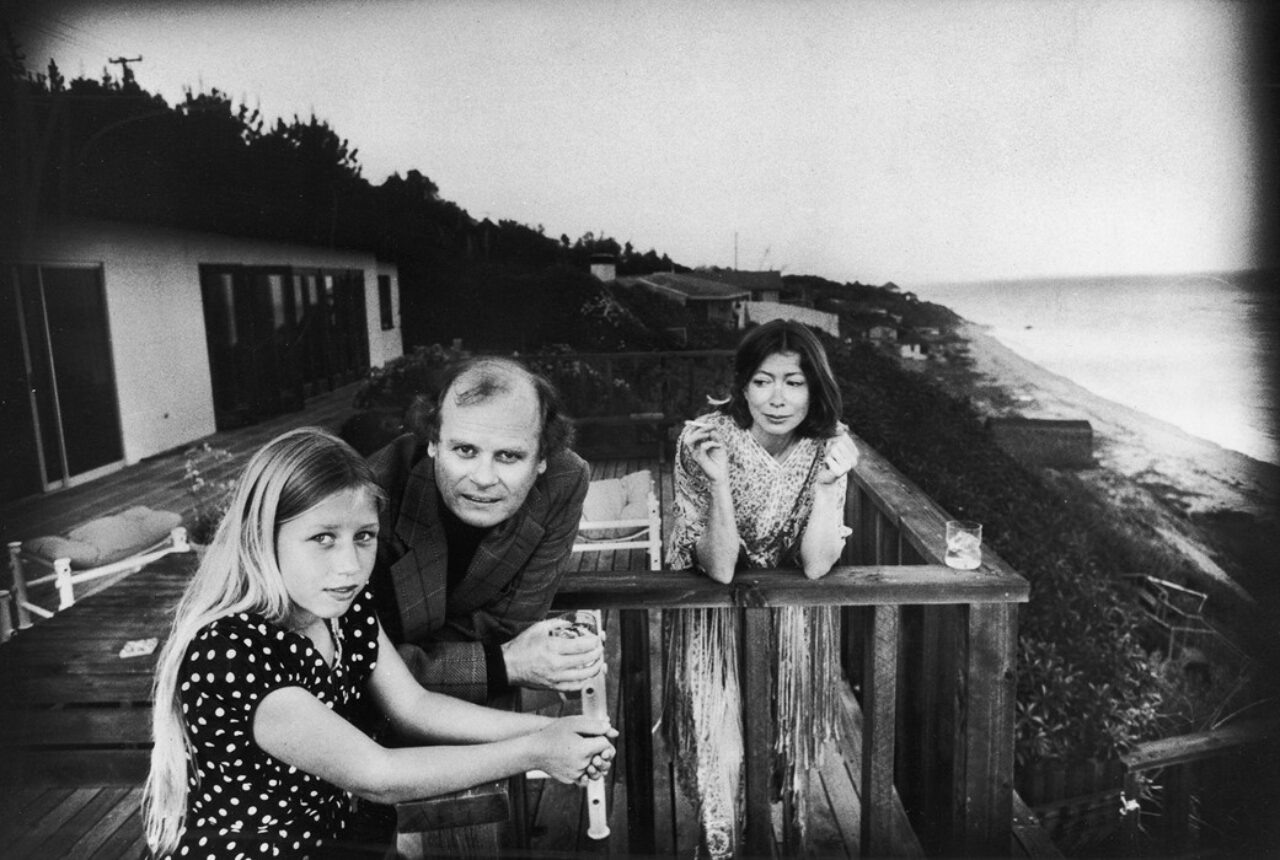

Didion was keen to be in the thick of the action and was able to slip, it seems almost unseen, into the places where it seemed this promising new California was being made. In the summer of free love, she hung out with Jim Morrison and his band in their recording studio, visited the Black Panthers in prison and bought dresses with Charles Manson’s girls.

Less utopia, what Didion experienced was more a trauma-scape of syringe strewn footpaths created by a generation of hippies who had ‘checked out’, been carried away by a drug-fuelled undercurrent, innocent flower children distracted by LSD being carried towards a dark fate. She wrote from the epicentre of the movement and observed a community that seemed to lack the moral grit to make good on the ideals and aspirations of her forefathers. For her, the so-called Golden Land was in the hands of zombie-like ‘dead heads’ who lived too close to the edge, never holding the wheel firmly in their grasp, always in danger of driving off the cliff at the very next bend.

Staying true to what she witnessed came at great emotional cost to Didion.

She walked frustrated against the now immortalised peace and free love tide of the time. Hers was an experience of loss and devastation for the future of her beloved California, her grief evident in the missing persons reports, street posters of abandoned children, mass shootings and cult fatalities she wrote about. Her words become almost a forewarning or incantation – when you check out of your own story, be prepared for darker forces to take your place and make it for you.

Later in her life Didion would experience and write of another type of personal loss. That of the death of her husband John Gregory Dunne and a few years later of their adopted daughter, Quintana Roo. She put her literary lens to these traumatic events in the devastatingly honest, insightful and autobiographical The Year of Magical Thinking (2005) and Blue Nights (2011).

True to her style of generating more questions than answers, Didion doesn’t offer advice or instruction on how we may find solace in our darkest moments, instead she asks questions about how strength of character is made, how we can be most present in the lives of our loved ones and invites us to consider how we may really be alive to the moments that shape us. If we believe as humans we have a need to ‘tell ourselves stories in order to live’ (Didion, 1973) then we must always be clear about what we want our story to be, and embrace our part in shaping the stories of the people and places we love most.

∆

An ode to Joan Didion | December 5, 1934 – December 23, 2021

Words: Magdalena Lane