ROBBY MÜLLER

The Master of Colour and Light Sees His Legacy Continue In The Legendary Films He Made

Robby Müller, Dutch cinematographer and master of colour and light, has forever changed the game for cinema worldwide.

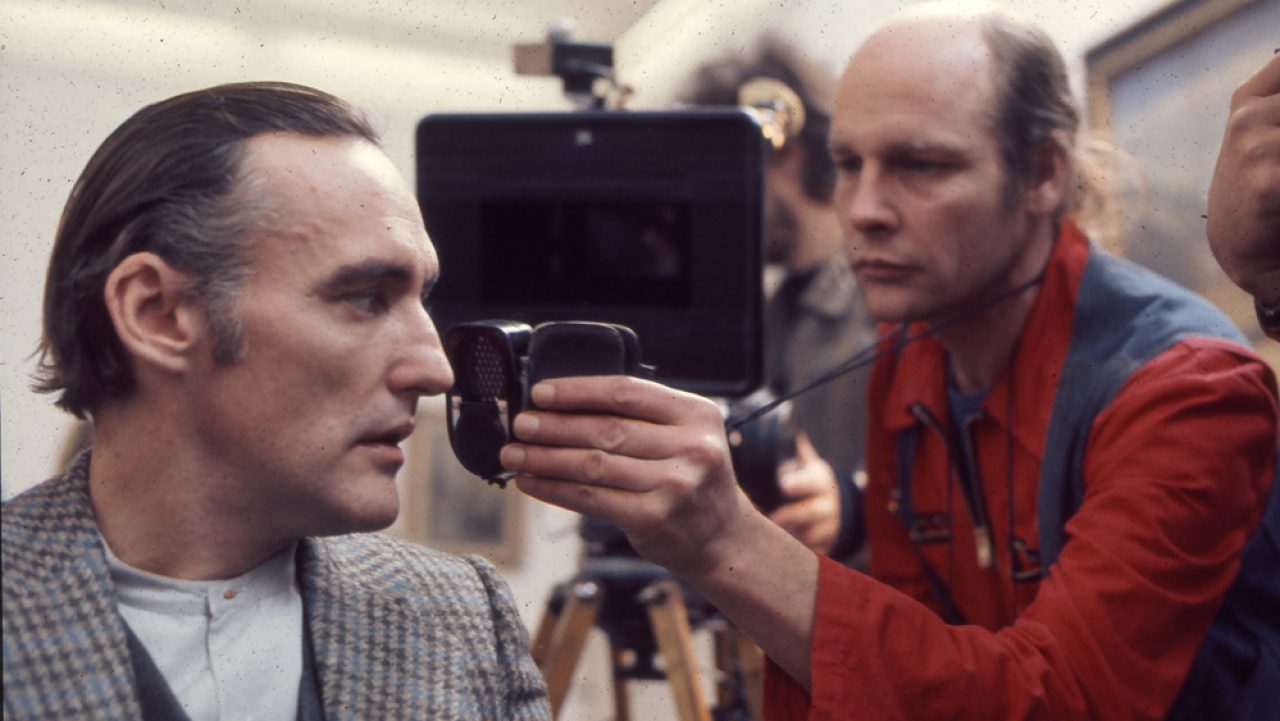

His visionary work is instantly-recognisable, with his ability to intuitively find a rhythm within a scene, and – using light and colour – to transform it to an effect which is absolutely incomparable. Best known for his work as director of photography for Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas, Lars Von Trier’s Breaking The Waves and Jim Jarmusch’s Down By Law, Müller would always operated his own camera, which enabled him to explore his intuitive sense to innovate with no bounds. Loved by the directors he worked with, admired by his peers, and studied by budding disciples, Müller is the subject of a new documentary recently premiered at the Venice Film Festival.

Living The Light – Robby Müller is a documentary film on the life and work of Müller, made by Dutch cinematographer Claire Pijman (her first documentary film), scored by Jim Jarmusch and Carter Logan. Painting a personal portrait of a man who made an immense contribution to cinema, Müller’s incredible vision is conveyed from the beginning and the viewer can instantly see: Müller’s empathy was at the core of his work.

Previously working with Müller, Pijman was one of the key collaborators on the major exhibition Master of Light: Robby Müller in the EYE Film museum in Amsterdam. Collecting directors interviews for the retrospective on Müller’s life work, it was this footage that Pijman had edited into the documentary to share, in the most concise and respectful way possible. It was also what helped finish the final funding for the film. After 4 years of collecting and compiling footage, and through the process of digitising Müller’s own personal videotapes, Pijman knew she could make the film, “When I put the first tape in, I was sold immediately, because I thought, “This is what he’s always talked about. This is his way of looking at things, working with light, studying light”. Müller’s love of archive held the secrets to his life’s work, and to the man himself.

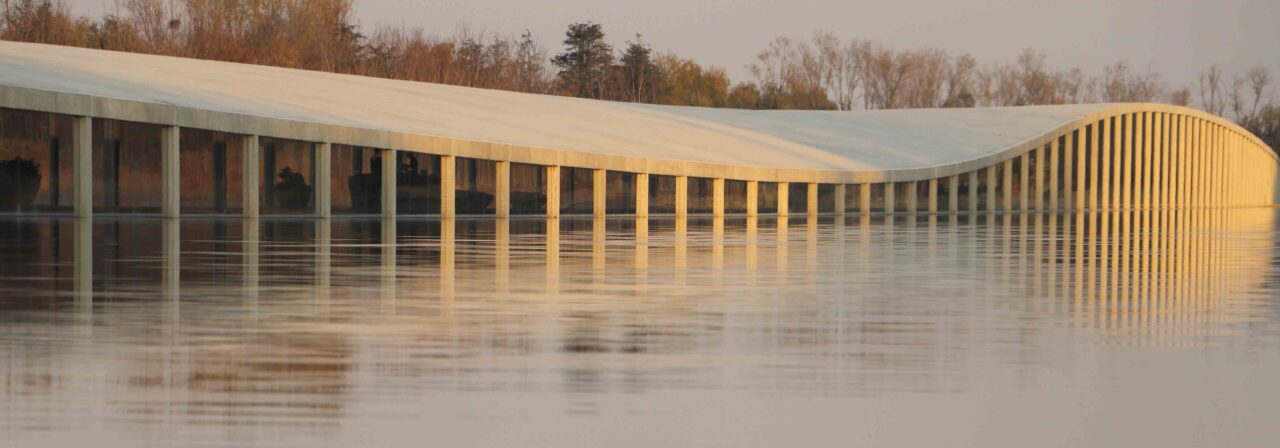

We first came across Müller’s work indeed at his retrospective in Amsterdam. On a last-minute stop to the EYE Filmmuseum – primarily to see the architecture and design of the building – we were offered a press ticket to see their main exhibiting show: Müller’s ‘Master of Light’ retrospective. At first, it was hard to grasp, ‘this major exhibition was for the work of a cinematographer?’, but why wouldn’t it be. Profoundly moving upon entry, the exhibition highlighted the importance of Müller’s work, equal to that of any director. Indeed the exhibition conveyed that Müller uniquely established his own signature aesthetic through his passionate and unconventional approach, and was incredibly pivotal to the film’s overall identity. He had a fine body of work, and had collaborated with the best: Wim Wenders, Jim Jarmusch, Lars Von Trier, Steve McQueen.

Walking through the show, Müller’s Hi8 video diaries were presented, along with letters and multiple polaroids that he would shoot on his travels (about 150 of 2000 total) and would later be published. In addition were Pijman’s video interviews with the directors that had collaborated with Müller, and screenings of his films. An immense body of work, presented fittingly in Amsterdam and in a film museum. So, when Pijman’s documentary film appeared on the schedule in Venice, we were one of the first in the cinema that afternoon.

Using basic elements with enthusiasm, Müller would use light in the most innovative ways. Timing of day and location informed how he would utilise light, but his innovative methods – what he came up through pure ingenuity – were the skills of his trade. The purity of light drove his work, and his methods and approach to the unconventional were another unique trait.

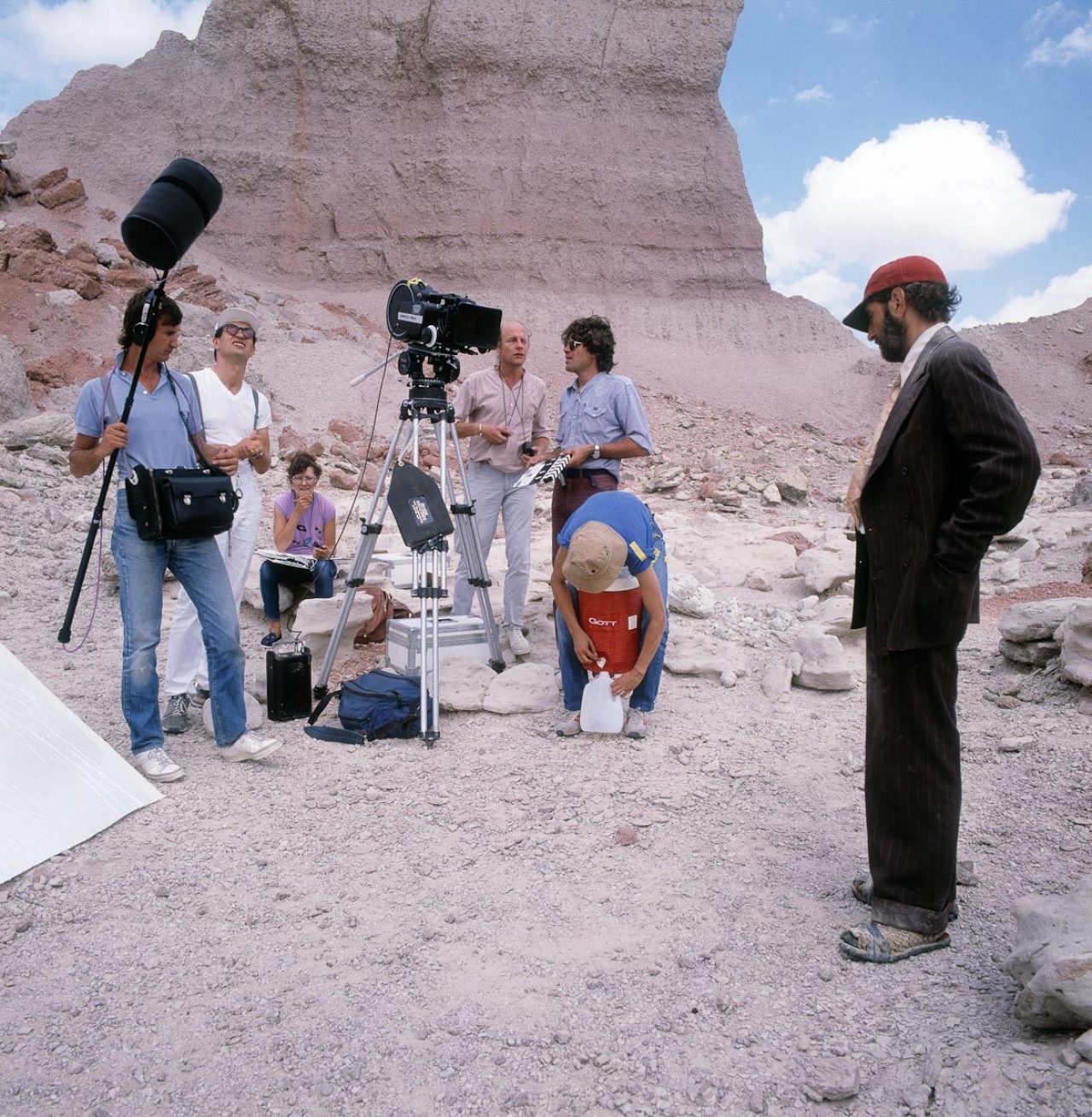

Born in Curacao in 1940, then a Dutch colony, Müller’s family moved to the Netherlands when he was 13. His father was an engineer for Shell, so the family later relocated to Indonesia and eventually ended up settling in Amsterdam. Studying cinematography and editing at the Dutch Film Academy from 1962 until 1964, Müller went on to work with Dutch cinematographer Gérard Vandenberg in West Germany, and it was here that he met Wim Wenders (5 years his junior). Wenders hired Müller to shoot a film-school short, later working on Wenders’ graduation film in 1970, Summer in the City. Beginning with experimental films, the two would go on to make over 40 movies together, and their partnership is considered one of the greatest director-cinematographer collaborations existing to this day. They worked on Alice in The Cities together, and when The American Friend was released in 1977, it was considered one of the greatest examples of cinematography at its best. Their film Paris, Texas which they worked on together, won the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 1984 – it is also regarded as a film which showed the American landscape like it had never been done before, upping the ante for directors of photography globally.

Müller’s deep knowledge of the technical aspects of filmmaking came second to his unique intuition. He was a versatile artist, and could find new tools to convey what he needed to. Working with Lars Von Trier on his Palme d’Or-winning Dancer In The Dark in 2000, Müller experimented with 100 stationery low-cost digital cameras to create a collage for a scene. He worked on something similar for Michael Winterbottom’s 24 Hour Party People shot in 2002, the last film he worked on (in addition to the short with McQueen). Depth and texture were found in Müller’s films with Jim Jarmusch, with some completely black and white in their execution. Films such as Mystery Train and Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai conveyed the essence of Müller’s work, with Dead Man and Down By Law finding a new appreciation in viewers for the black and white format. Jarmusch became a long-term collaborator and their respect for one another was mutual. Jarmusch would later explain, “He taught me later a lot about colour, as well, and how it relates to your emotions, or how the sky at magic hour changes every ten seconds and becomes a different shade”.

“I compare him to a blues musician in a way. He plays just a few chords and he conveys what he needs to convey. He’s a purist” stated filmmaker and artist Steve McQueen, whom Müller worked with on his Caribs’ Leap film installation for Documenta 2002. Müller would also work on a couple Hollywood films (Repo Man, To Live and Die in L.A.,and Barfly) but would later reject them, as he preferred to work with directors whom allowed him creative freedom and trusted in his vision and approach. He always prioritised working on films with a story, rather than just judging on genre, citing: “When I choose to work on a film, the most important thing to me is that it is about human feelings. I try to work with directors who want their films to touch the audience, and make people discuss what the film was about long after they have left the cinema.”

He passed away in June this year, at the age of 78, and left deep impressions on those he worked with and those who experienced his work (Jim Jarmusch stated in a tweet: “I love him so very much. He taught me so many things, and without him, I don’t think I would know anything about filmmaking”). Müller had suffered from vascular dementia – which was a degenerative disease preventing him from speaking and walking – but he could however still understand what was going on around him, as translated by his wife Andrea a photo editor, whom had married Müller in 1993 and had been together ever since.

Leaving behind a body of work of over 70 films, Robby Müller’s legacy will live on in the incredible films he created, and those he inspires to seek truth and beauty in the light.

∆

Living The Light: Robby Müller is now available via Moondocs and soon at all good cinemas

Written by Monique Kawecki | All images as credited