NASA – PAST AND PRESENT DREAMS OF THE FUTURE

After Almost A Decade in Progress, British Photographer Benedict Redgrove Releases His Most Ambitious Project Yet

British photographer Benedict Redgrove’s documentation of NASA (The National Aeronautics and Space Administration)’s most iconic and technical objects is finally getting an opportunity to be published after nine years in the making. Titled NASA – Past and Present Dreams of the Future, the book will feature over 200 photographs each shot specifically by Redgrove.

We speak with Redgrove ahead of his Kickstarter to launch the book, as he embarks to self-publish and ensure the highest quality of production remains, working closely with Marcel Meesters Art Book printing in Luxembourg. There are only four more days to support and purchase Redgrove’s first book, with his Kickstarter ending on August 18. A large-scale exhibition of the work will then be presented in November.

In NASA – Past and Present Dreams of the Future, Redgrove highlights NASA’s archive in a way that until now, has never before been seen. Uncovered and reframed only through his unrelenting persistence and dedication, the project is one which may not have ever seen the light of day. Self-funded and self-organised, the project took Redgrove to NASA’s bases across the USA on multiple visits over four condensed years in the NASA Houston, Florida, and Louisiana locations.

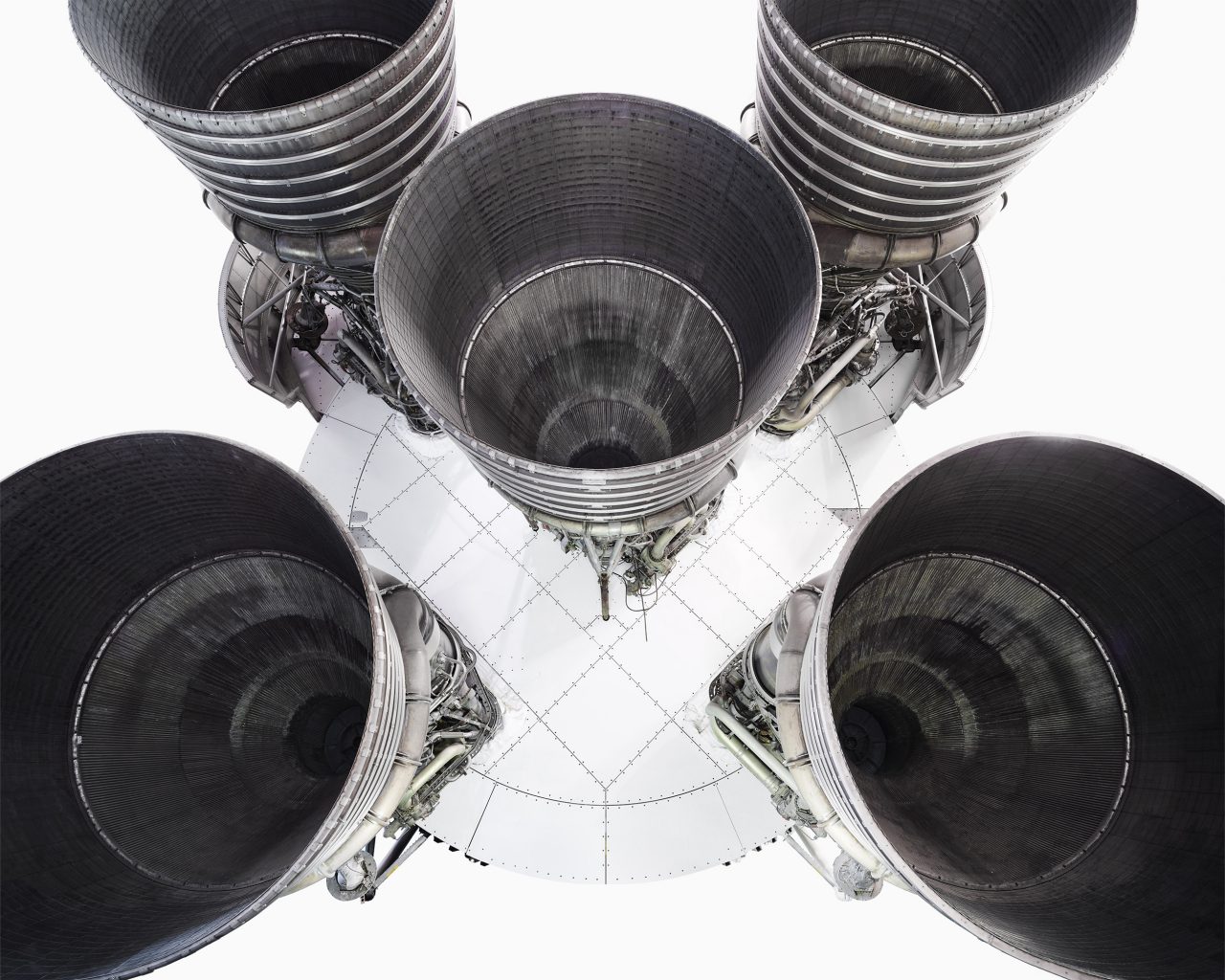

Beautifully crafted in the photographer’s very distinctive style, attention to detail is the focus for the photographs. Objects are shot with a white background to highlight their incredible design details, providing viewers further insight into their production. They highlight the enormous amount of innovation required to advance in space exploration, and also how far we have come in doing so. The quest continues.

It is a testament to one man’s passion for NASA. Redgrove’s images showcase the best of human potential and where it can go from here.

Benedict, can you tell us more about this incredible journey you’ve embarked on?

It’s been a total rollercoaster. This was started nine years ago with a conversation with a friend of mine at a studio in New York. The project originated from another project which I led, and explored how certain jobs require certain suits to do that job. That led into the NASA project where I wanted to shoot space suits and grew more and more to be about NASA. I’ve just loved NASA since I’ve been a child, and I still hold them in such high esteem. Everything from the suits to the [air]crafts were held in such high reverence, it suddenly has a deep transformative energy to me. Whenever I’ve been working on a project, that’s something I really want to convey to people.

With NASA – Past and Present Dreams of the Future, can you tell us more about your publishing process?

We’re used to seeing the images all digitally. Shot on digital cameras, with digital backs anyway, very high resolution, and then they’re worked on digitally, and then we print them. Either on a digital printer or C-type printer. That transference from digital to print is a very different process. The book is going to be another leap into that. Something tangible that everyone can have.

As the project has taken so long to produce, I spoke with a couple of publishers about working with them to produce the book. They were really keen to do it, but the more I got talking to them the more I realised they didn’t quite get a handle on what the project was about and it just felt they weren’t going to put in what I was going to put in. I spoke to a few friends who have self-published before and it sounded like the route to go down. I have more control, and I’d be producing the book that I wanted to produce. So my design background kind of works in that favour.

As a 9-year-long project, how did you first approach NASA? You’ve mentioned the project as self-initiated and self-funded.

It was a really long process. The project has taken nine years, five years of that was that process [of connecting with NASA]. It’s been four years of shooting, but five years of trying to get to see the right people. Because it’s such a huge organisation, it takes a while to get to the right person to speak to.

It all started off by talking to Bill Ayrey at ILC Dover, Delaware, who make the spacesuits. He allowed me to shoot one of the suits in the test facility, we did the shots, sent them back to him, and said ‘this is what we’d like to do for the project, can you help introduce me to anyone at NASA’. He then did introduce me, and that got the ball rolling.

It took about a year and a half to get to that stage, and then I did need to use my connections at WIRED magazine for them to give me a sense of authority for NASA.

Which of the NASA locations have you visited for the photo series?

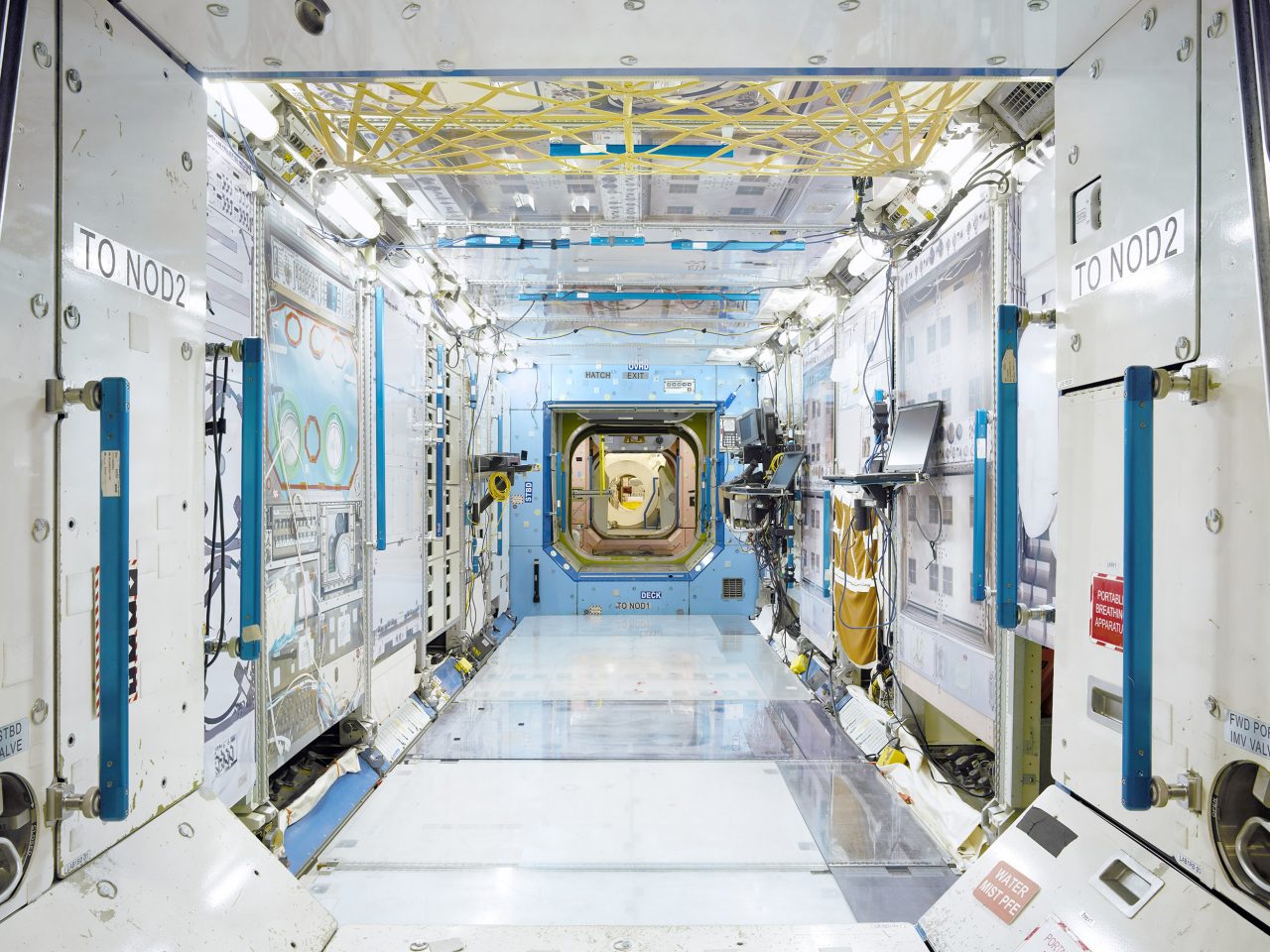

NASA are an American body, but they’ve got tie-in’s with Japan, Canada and so on. There is the Canadian arm and space station, there’s also an aviation module and a Japanese module, tie-in’s with Russia and the space station, and the European Space Agency. They have divisions all over, however I went to all their locations in America.

The Johnson Space Centre, where they have the manned-flight path, the Kennedy which is where they launch from, and then the Michoud and Marshall Flight Centre down in Louisiana where they build and test the engines and rocket paths. The Smithsonian as well, which has a large collection of about everything.

There’s certain areas that I knew I wanted to photograph, and there are certain areas that opened up more, the more that we worked with them [NASA]. Eventually they would invite us into areas that normally we would not have known about. I started submitting additional ideas of what I wanted to cover, and that’s when they started opening up extra doors as well.

There were moments on shoots when, for instance, they gave me one of the Lunar Training Hasselblad cameras to hold for a while, which is quite a ridiculous object – especially if you’re a photographer! There would be other moments when it was quite difficult to take in what we’d just seen, or experienced. It would normally take a couple of days once we got back to London and were working on the images, there would be a moment when you just realise what it is and what you’ve seen.

We went inside the Lunar Vaults, which is where all the original moon rocks from the Apollo missions are held, and they’re all still sealed in their nitrogen boxes in safes, and then again in another nitrogen seal. There is all those kind of events that myself and my assistant would be in, that no-one gets to go into, and not without good clearance. There were just some really cool moments. I was standing inside of mission control with the mission controller, talking to her, while astronauts were on the sleep program and we were watching the sunset behind Earth on space station cameras. Just as an experience, it’s quite a cool thing. My assistants aren’t necessarily into space program at all but they would come away thinking that this is incredible.

How many assistants do you work with?

I always travel with one assistant, unless we needed more people there. Sometimes I’ll get someone from California to come and meet us, so I have some assistants that I work with there. Normally it is just my UK assistant that travels with me. Small crew, much easier, less hassle.

It’s a lot of pre-production and knowing how I want the project to exactly look at the end as an overall body of work, which was sort of developed over the 4 years.

My background is definitely in visual language. When I was a kid I had learning difficulties, and the way I’d learn to read and write was very much not in a conventional way – it was in a completely visual way. I think that transferred. You can see it in my sentence structures, my mind goes off in so many different tangents. When I can focus on something like this project, its very much a black-and-white area for me. Very formulated and regimented, structured.

Letting the subject speak for itself…

That’s why they’re stripped back. There are locations that we’ve shot, as they are locations that I’m talking about, but when it’s an object, it should just be that single object you’re focussing on. I don’t want viewers to be detracted. Viewers should be solely looking at the item, trying to understand what it is, what its relevance is, and how it makes you feel.

The white of the background is a pure palette for you to get a gage on the colours and sense of materials that are in the objects. My retouchers say that I see an extra grade of white, because there are so any shades of white in these objects that its really important that they are kept. So, the printing of the book is going to be tricky. The paper will determine alot and it’s also the tonality of the inks and whether we can match the tonality we have on the files. That’s going to be a real struggle. The book is quite expensive, but that’s why, the detail in there is quite strong. We’re printing with Marcel Meesters in Luxembourg, who is also a one man band and a man that really cares about what he wants to do. It’s really important to surround yourself with people that you trust. That’s the big thing.

∆

EXTRAVEHICULAR MOBILITY UNIT (EMU) SPACE SUIT Designed in the early 1980s, this two-piece suit is the result of years of research and development and still currently used by astronauts (whilst the Z Series is currently being tested).

The EMU suit has been specifically designed to protect and facilitate astronauts whilst in orbit. A soft lower torso locks with a hard upper shell, and controls on the front of the suit have text written backwards so astronauts can see them when viewed through the mirror attached to their sleeves. The colour white is used to reflect heat and visibility against the blackness of space.

GENE CERNAN’S APOLLO AZL SPACE SUIT TRAINING GLOVE Worn by astronaut Gene Cernan during training for Apollo 17 (the last manned mission to the Moon), this space training suit glove is now situated at the Johnson Space Centre where it has been photographed by Redgrove.

Cernan’s gloves were specifically designed for use on the lunar surface and their design reflects their use. The blue silicone rubber fingertips provide sensitivity, whilst the outer shell is made of Chromel-R fabric to allow handling of extremely hot or cold objects. In general, there are different types of gloves for work inside and outside the spacecraft for astronauts. Inside gloves are made from a cast of each astronaut’s hand.

ARMSTRONG’S RUBBER STAMP Used on all of Neil Armstrong’s space suits, this rubber stamp provided a pivotal alternative to sewn-in name tags for astronauts’ suits.

Name badges sewn in with a pin would destroy pressurised space suits, so the humble rubber stamp was commonly used to label astronauts’ suits, gloves and other apparel. We particularly admire the font used! Benedict Redgrove found and photographed the stamp at the Johnson Space Centre in Houston.

LUNAR TEST ARTICLE 8 (LTA8) Photographed by Redgrove at the Space Station in Houston, this lunar module test version was created to prove that the machine could safely transport astronauts to and from the lunar surface. This model’s twin currently resides in The Sea of Tranquility, the landing site of Apollo 11.