LOUISE BOURGEOIS

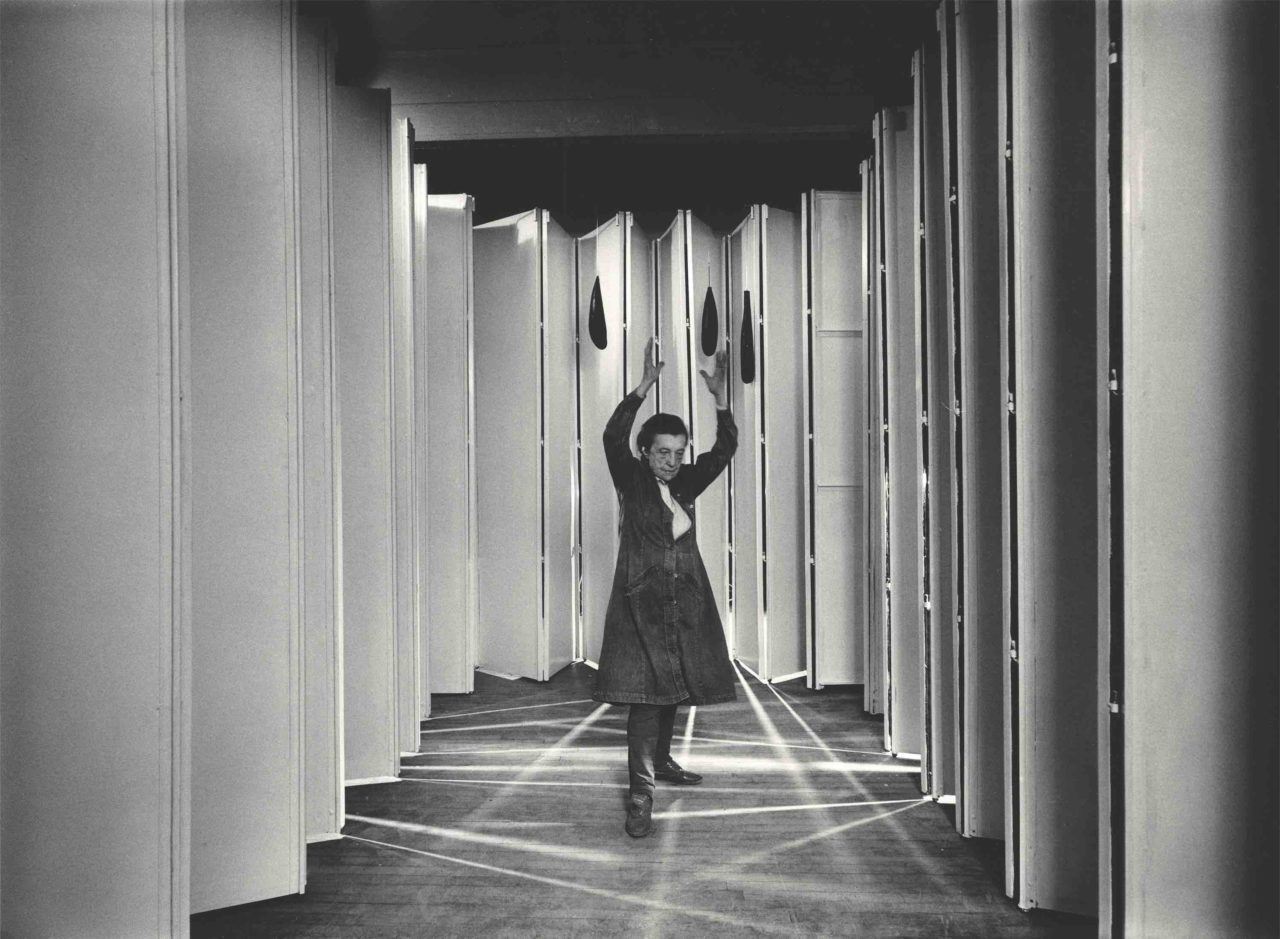

STRUCTURES OF EXISTENCE: THE CELLS

An influential figure in modern and contemporary art, Louise Bourgeois was as complex and intelligent as her art is.

A French sculptor, painter and printmaker, she broke boundaries in her own work with the exercise of abstract forms and the endless possibilities of working with various media.

Her lifetime from 1911 to 2010 has seen her work extend beyond genre, her created concepts and formal inventions are now key moments in contemporary art. The work highly emotive, Bourgeois herself is a person of extreme highs and lows and it was this consciousness and expressed emotion that was an instigator for her work.

Born 1911 in Paris to French parents, Bourgeois’ mother and father owned a gallery that dealt in specific antique tapestries. With their business later moving to Choisy-le-Roi and focusing on tapestry restoration in a workshop below their apartment. A sensitive relationship with her father became important subject matter for Bourgeois later in her life. She described her mother as “an intelligent, patient and enduring, if not calculating, person” who would turn a blind eye to her father’s infidelity with their English teacher and nanny.

Bourgeois went on to study mathematics and geometry at the Sorbonne, but her mother’s death in 1932 initiated a conversion to study art. Whilst her father refused to assist her studies of art financially, Bourgeois joined classes that required English-speaking students, whereby she would translate for free tuition. Following her studies at the Sorbonne, Bourgeois went on to study at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, the École des Beaux-Arts and the École du Louvre. Bourgeois frequently visited artists studios in Paris, assisting and learning techniques. Later working in her own gallery, Bourgeois met her future husband Robert Goldwater who was an American art historian. Together they emigrated to New York City that same year, with Goldwater continuing his teaching and Bourgeois attending the Art Students League of New York.

With emotion always at the core, sculpture remained a strength of Bourgeois’, and she would create early work from junkyard scraps and driftwood. This explained the situation for artists in New York at the time (financially difficult with opportunities slim), and with the addition of being a female artist, it was quite a challenge for Bourgeois to gain any attention. Her sculpture work later began to evolve and utilised materials such as marble, plaster and bronze. Any conflicts empowered Bourgeois and her work, and through this any attachment would be released.

Bourgeois was also a teacher at the Pratt Institute, Cooper Union, Brooklyn College and the New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture in addition to various public schools on Long Island. During the 70s, Bourgeois would hold gatherings at her home in Chelsea. It was a terraced house on West 22nd Street that her and her husband had moved into in 1958, and Bourgeois continued to live and work there until the end of her life. Titled ‘Sunday, bloody Sunday’ the gatherings would find young artists and students bound in conversation with Bourgeois and their work often critiqued. A teacher and mentor to many, Bourgeois was an instinctive communicator above all.

Space does not exist; it is just a metaphor for the structure of our existence.

In 1980 the acquisition of Bourgeois’ first large studio saw a progression to produce larger works. It was recognised that the rooms in her Chelsea townhouse were only around 4 metres in width, and this move to a larger studio saw Bourgeois create some of her greatest works.

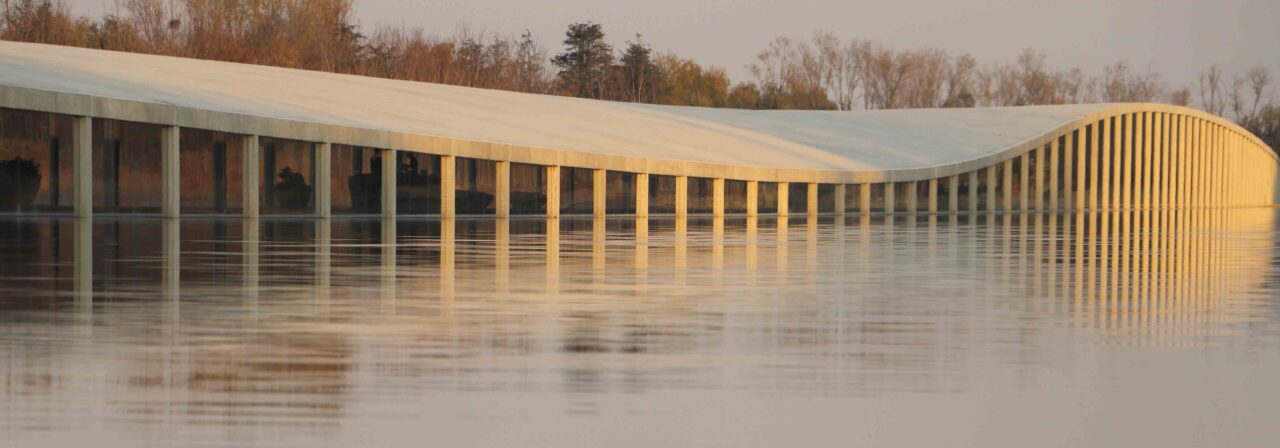

The Brooklyn studio also saw Bourgeois work with new raw materials, objects from the surrounding neighbourhood (and even from Bourgeois’ own private life) are found in certain Cell works. Steel shelves from a sewing factory can be found in Articulated Lair, 1986, a water tank taken from the roof is used in Precious Liquids, 1992 and the spiral staircase Bourgeois kept when she had to evacuate the studio in 2005 was used in Cell [The Last Climb], 2008.

One of her last Cells, Cell [The Last Climb], 2008 is showcased in Structures of Existence: The Cells, along with her other Cells works created over two decades.

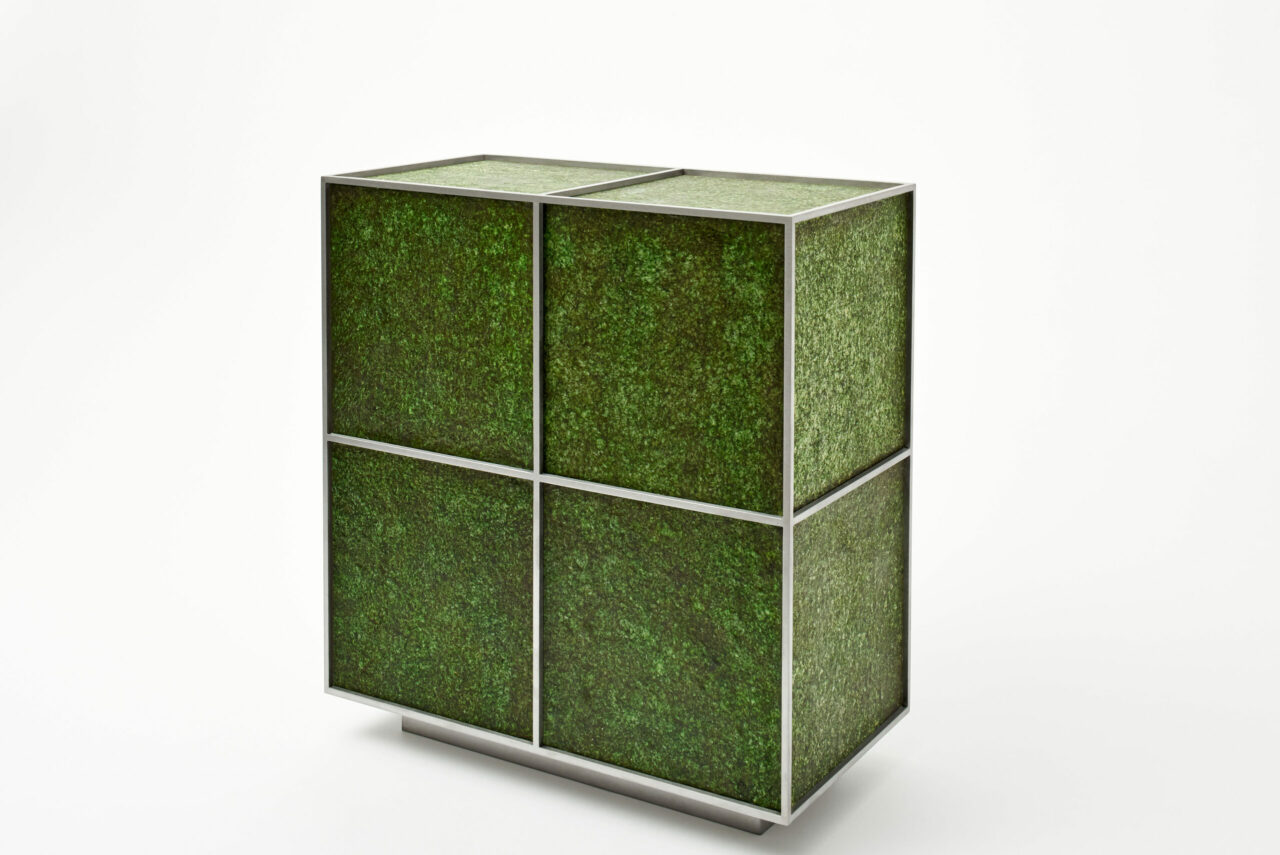

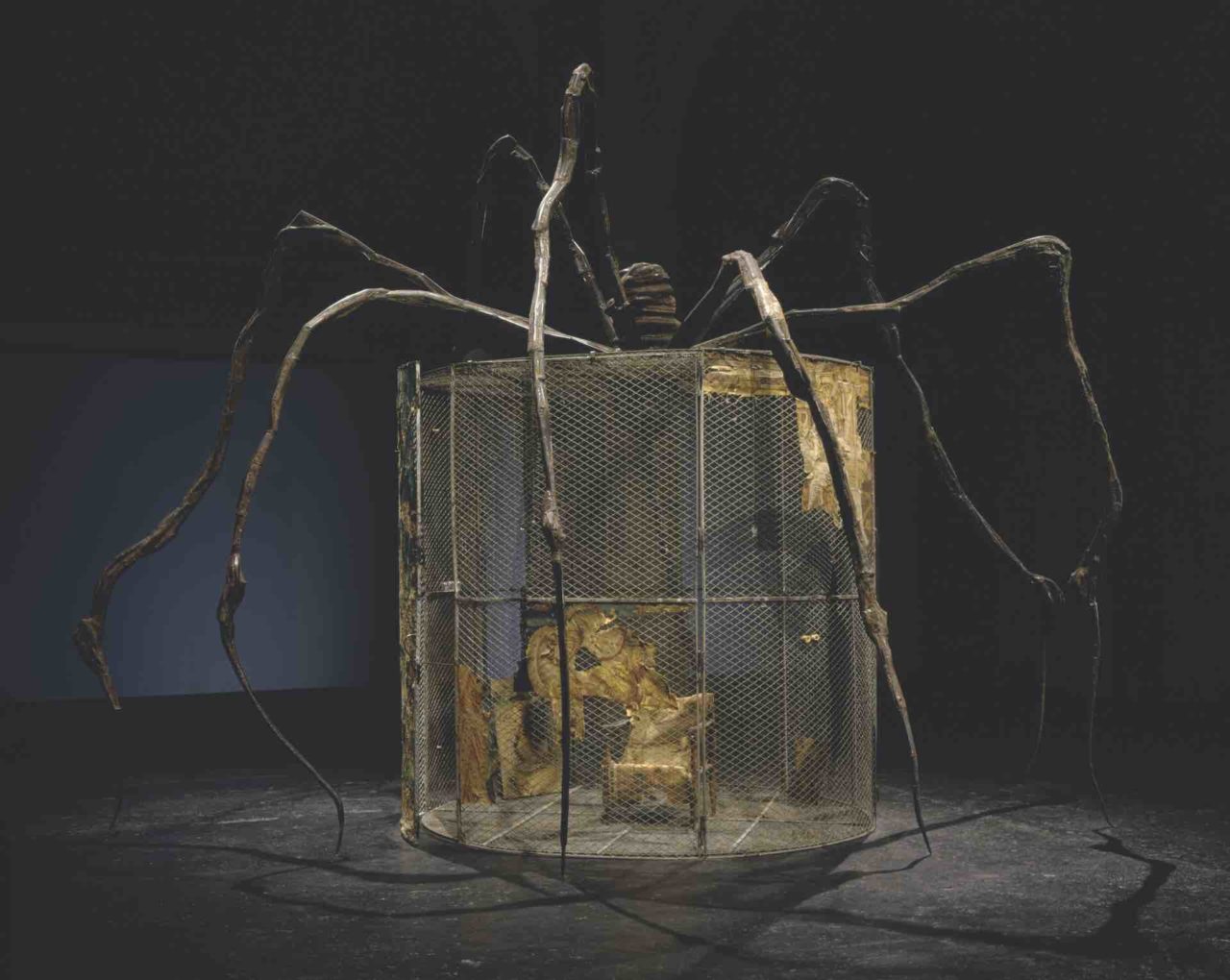

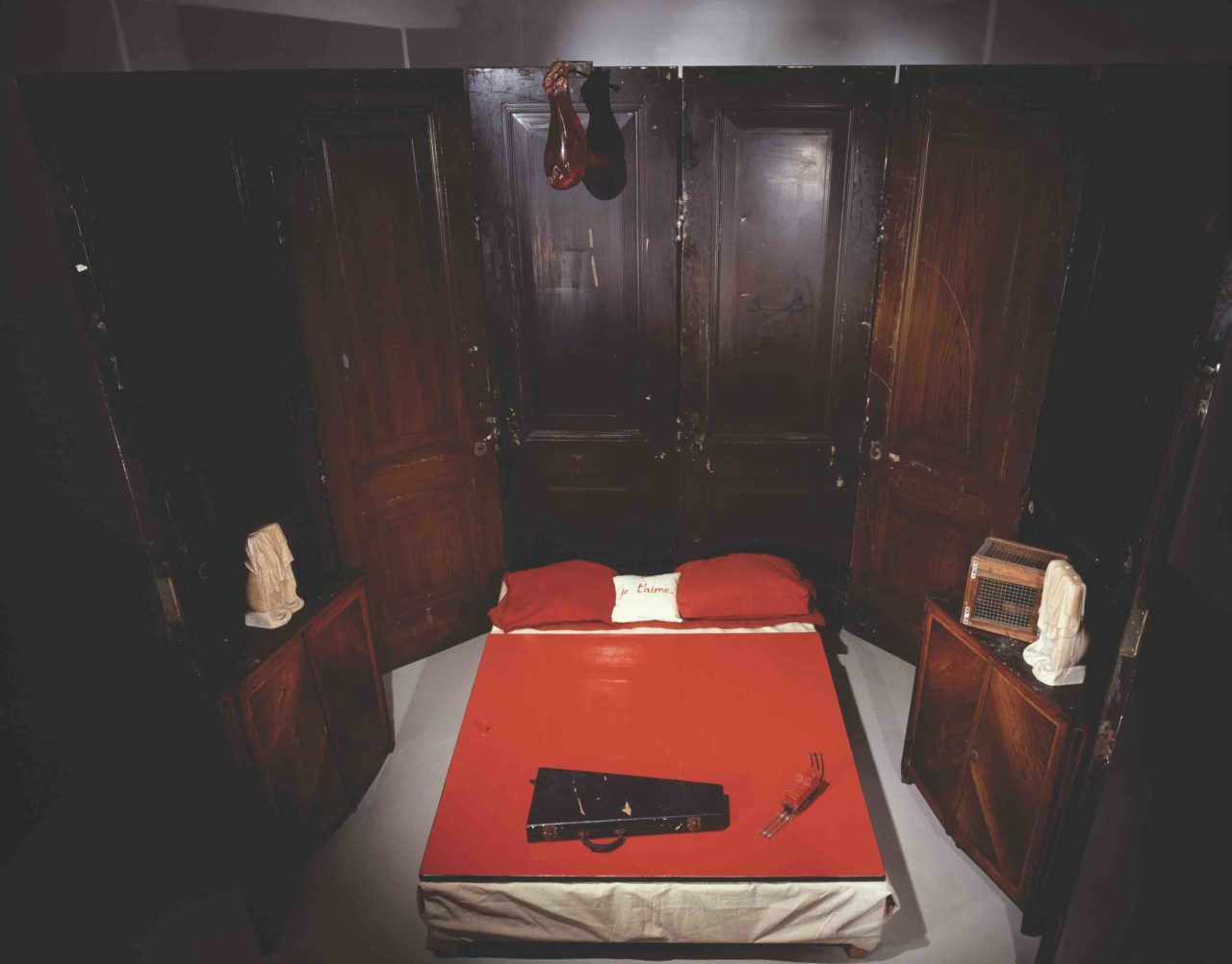

The Cell series is a large body of work, regarded as some of Bourgeois’ most sophisticated and innovative. The Cell series emphasise architectural space through their scale and viewer interaction. Although each Cell is an enclosure of its own world, it is one so humane that is easily identified and resonated with.

Compiled with found objects, clothes, fabric and furniture, it is hard not to experience the emotionally charged Cells without them getting to ones core. There is a strong narrative in the theatrical sets in each Cell, that one can only be whisked (mentally, and in certain works physically) into each enclosure.

Bourgeois’ Cells work represent different types of emotions and in particular, pain: physical, motional and psychological. The work is autobiographical, a physical explanation of her emotive self. One can resonate with the questioning, then unravelling, of complex topics to find understanding. The entire series’ motivation of simultaneously remembering and forgetting, is best described by Bourgeois, “You have to tell your story and you have to forget your story. You forget and forgive. It liberates you.”

The exhibition Structures of Existence: The Cells is the largest overview presentation of this particular body of work to date. Planned and organised by the Haus der Kunst, curator Julienne Lorz worked closely with Bourgeois’ long-term assistant and carer Jerry Gorovoy to complete its display. Including five precursor works that emerged with Articulated Lair in 1986, Bourgeois created a total of 60 Cells, of which 30 are displayed in the Haus der Kunst (along with 2 precursor works).

Curator Julienne Lorz explains that Bourgeois’ Cells “occupy a place somewhere between museum panoramic, theatrical staging, environment, installation, and sculpture, which, in this form and quantity, is without precedent in the history of art”. They are a new sculptural category. Two titans coming together for an experience that is almost impossible to replicate anywhere else, Structures Of Existence: The Cells is one of the most powerful museum experiences one can have with a remarkable body of work such as this.

As a non-collecting museum, the Haus der Kunst also insist they do not show retrospectives but delve deeper into surveys of an artists work. Structures Of Existence: The Cells showcases the complexities of one of the most remarkable artists of our time, connecting through interaction, experience and in the latter: memory.

∆

Images as credited | Written by Monique Kawecki [Champ Editor-in-Chief]

This article was first published in Champ Magazine issue 10