Lee Ufan

The Renowned Korean-Japanese Artist Meets With Champ Editor Joanna Kawecki

Born in 1936 to a homemaker mother and a liberal newspaper journalist father, artist Lee Ufan was raised in a rural mountain village in South-Eastern province of Gyeongsangnam-do in Korea, during a time of political turmoil and cultural change. His background is a true reflection of his influential and important artwork today.

After visiting an ill uncle in Yokohama (Japan) in 1956, Ufan made the decision to move from Korea to Tokyo and continue his education and pursuit of artistic practice. With an interest in philosophy, phenomenology and structuralism, he attended Nihon University, and together with a growing knowledge of Abstract Expressionism and Art Informel, his exploration of abstract paintings and repetitive marking, piercing, and chiseling to investigate the textural qualities of materials was prolific.

Throughout the exploration of his art practice, he was a writer and art critic himself, and was pivotal in introducing new practices or movements, such as the Korean monochrome painting movement Dansaekhwa, also known as the Ecole de Seoul. In addition to his artworks, Ufan was an active critic too. One infamous essay on the artist Nobuo Sekine in 1969, would later become the foundation for Mono-ha, an avant-garde Japanese art movement that Lee Ufan was one of the founders of.

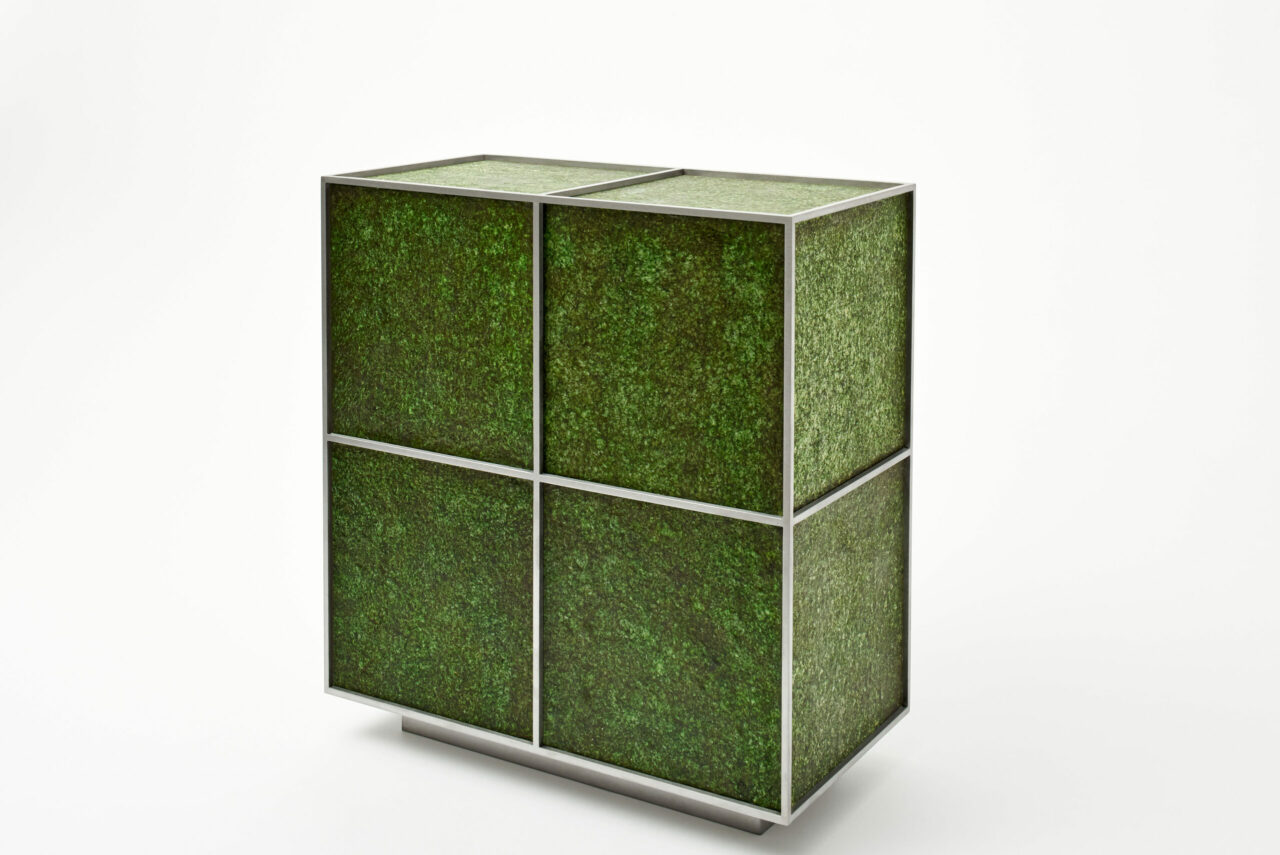

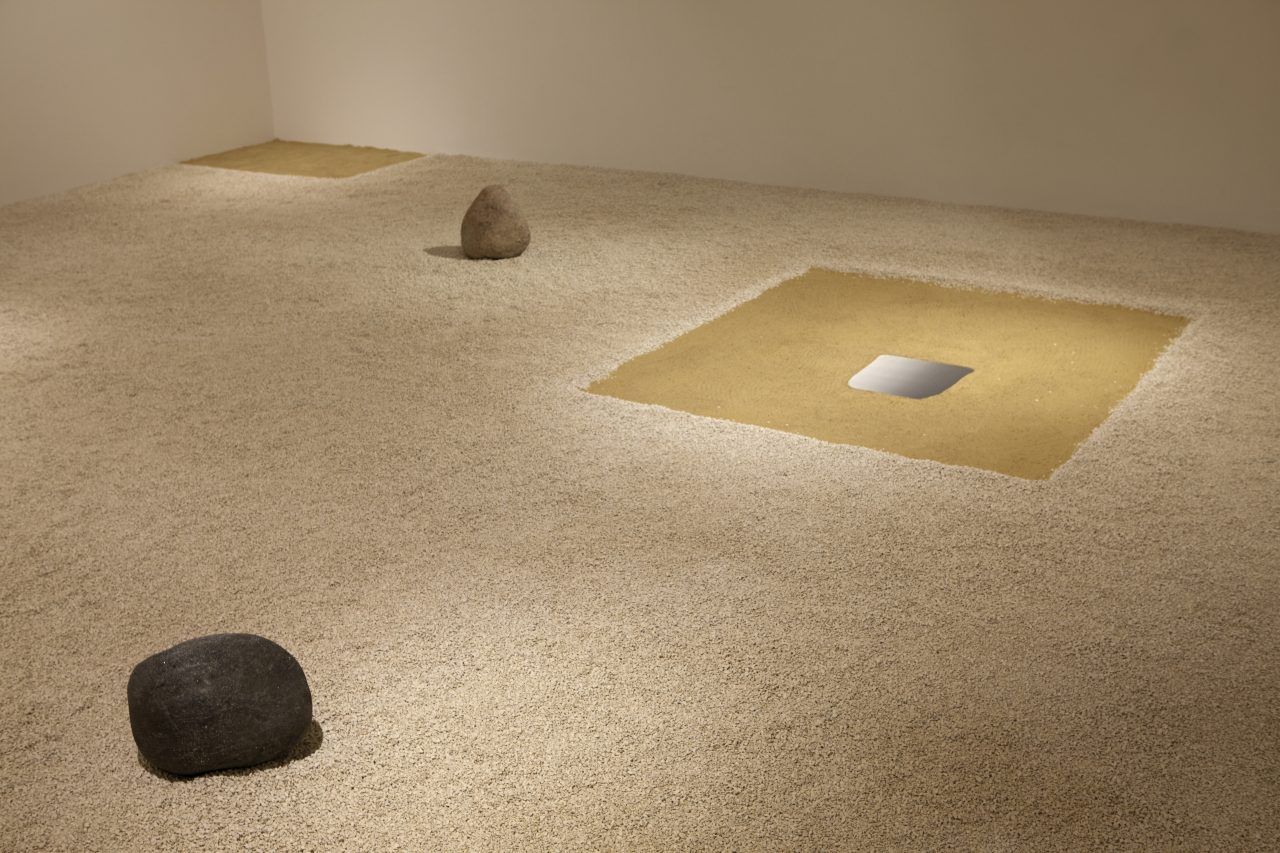

Mono-ha translated to ‘Object School’ or, ‘School of Things’, and in the late 1960’s emphasised materials, perception and interrelationships between space and matter. The founding group were all mostly graduate students of Tokyo’s Tama Art University between the exciting yet tumultuous time roughly from 1968 to 1973. Mono-ha artworks demanded a sense of calm and patience, slowing things down upon reflection and understanding. It counteracted modernism, and instead emphasised on what was not present. With a focus on experiential ideas and works, most pieces were temporary, and with such a short life span, there were no buyers due to difficulty in obtaining or maintaining the pieces. They were a complete contrast to the highly commoditised colourful pop artwork often seen today.

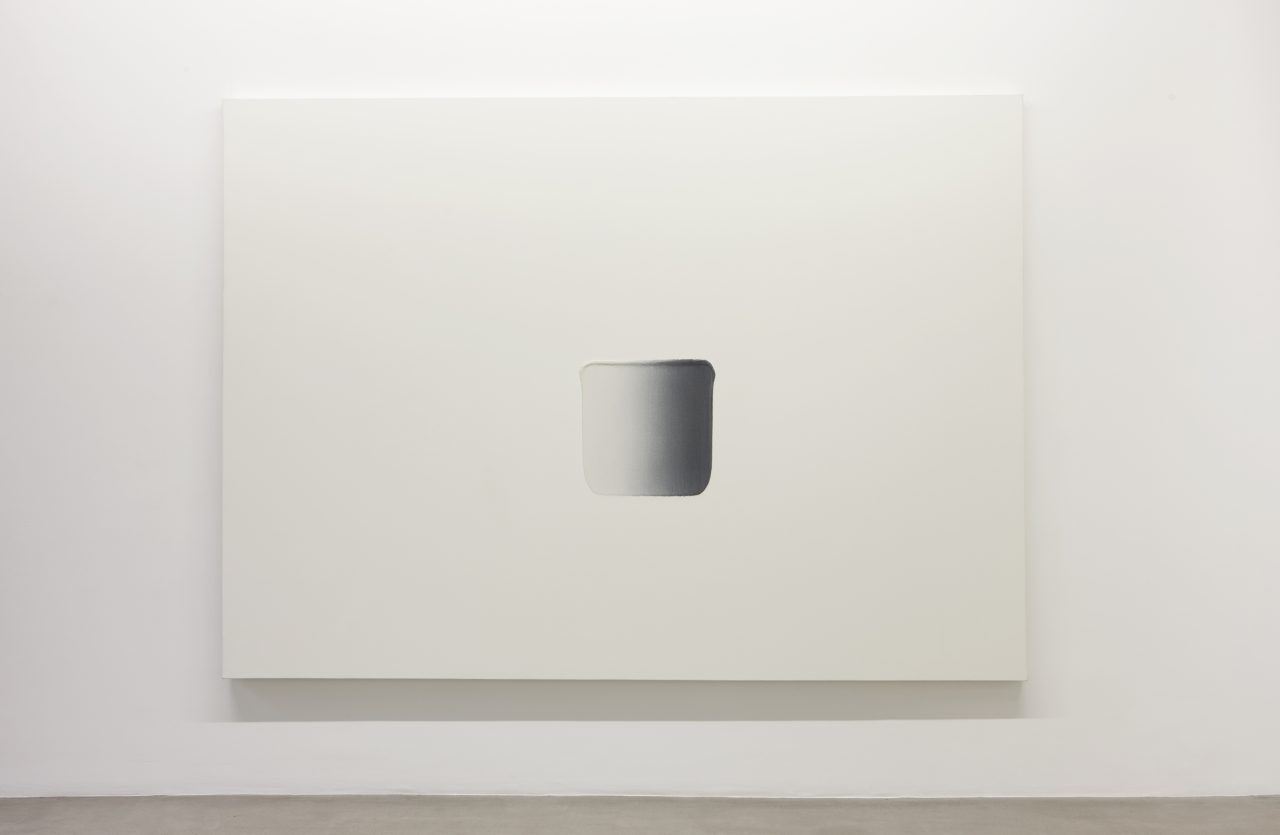

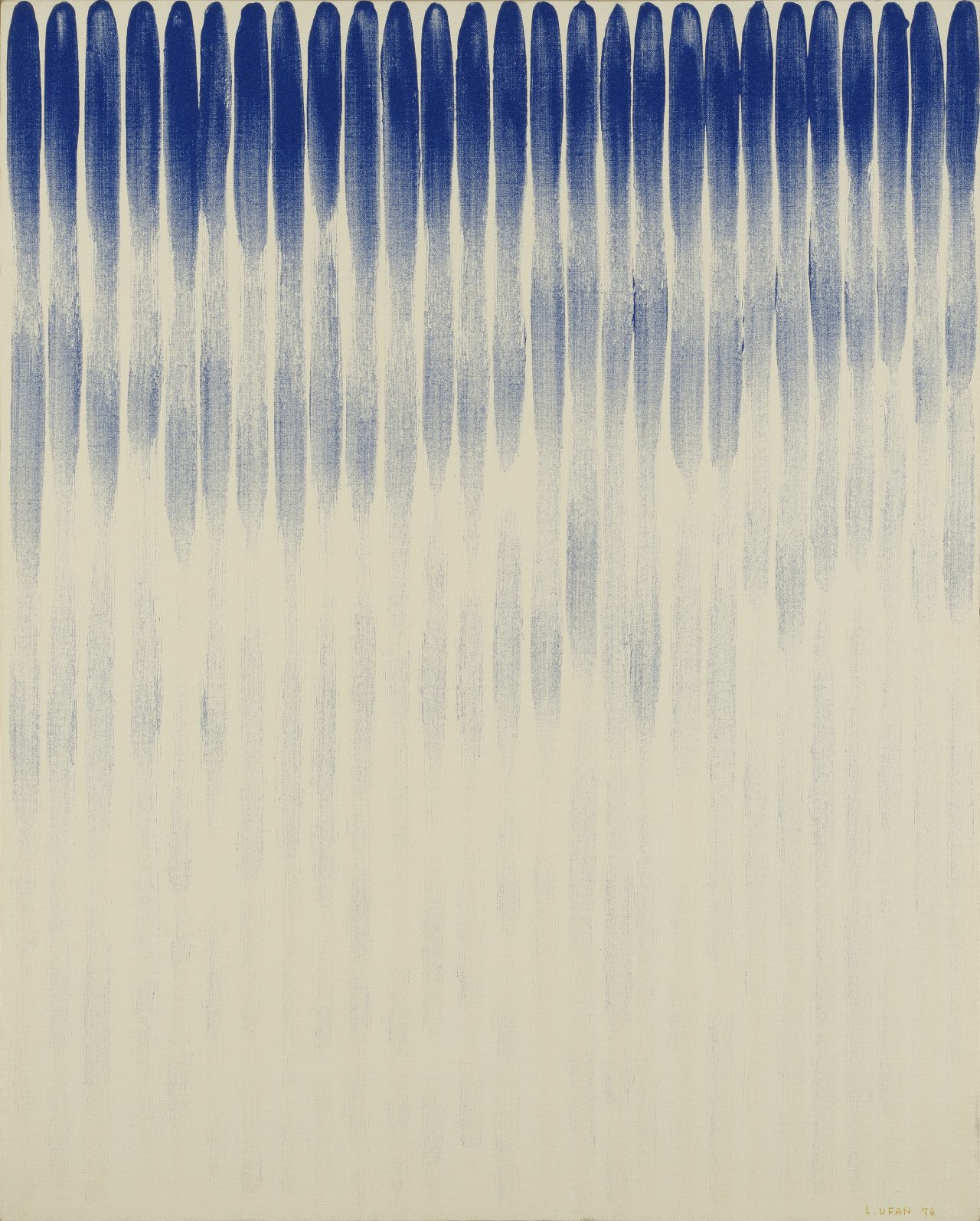

Lee Ufan’s simplicity and reduction seen in his sculptural works of steel and stone, are quiet and reductive paintings in blue or grey. He exclaimed; “Blue is the most distant colour. Difficult to reach as the sky. Containing both life and death. It is the colour of nothingness.”

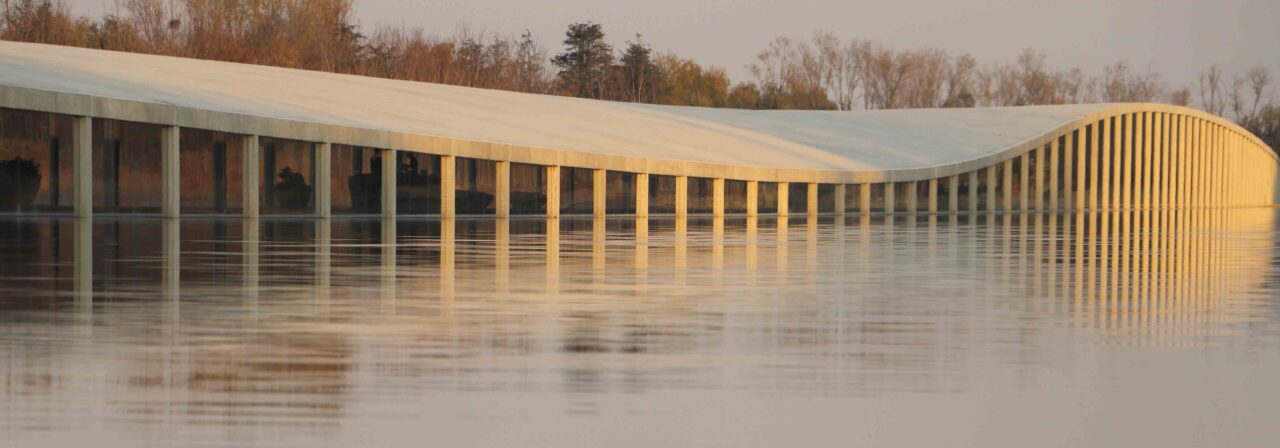

With work in numerous public collections, from the Tate Modern Gallery in London, to the Nationalgalerie in Berlin, or privately shown by Galerie Kamel Mennour in Paris, Ufan’s influential work continues to be immeasurable. In Japan’s Naoshima Island, the Lee Ufan Museum can found be found showcasing the works of Ufan, in a contemplative space and architecture in collaboration with renowned Japanese architect Tadao Ando. “Tadao Ando is an old friend who I trust. I have always wanted to work with him one day.” Positioned in isolation in a valley surrounded by mountains and sea, the museum offers a harmony between nature, architecture, and art, it is the perfect place for reflection and meditation as Ufan’s work encourages.

In addition, June 2014 saw the renowned Chateau de Versailles in France showcase Ufan’s artwork in their vast outdoor garden space, allowing visitors an experiential moment amongst the grandeur of site-specific works. Materials such as stone and steel, the signature materials of Ufan’s work, uniquely sat naturally alongside the surrounding environment as if they had always coexisted. The experience of the location was also part of the experience of the works. “My work even if it’s the same one, has the characteristics of looking different depending on the place. It is because space, location, and background are part of the work.” Amongst the many considered locations was ‘Earth of the Bridge’, confronting the viewer and forcing them to cross the steel artwork, past it’s two surrounding stones, to break the invisible boundary between work and viewer. This interaction is a welcome reminder to our approach towards art. Individually, it is up to the viewer to interpret the works, and allow curiosity to introduce a new way of viewing, and interacting with, art.

Currently living between Paris and Kamakura in Japan, Lee Ufan continues his practice and exhibiting artworks worldwide. He understands that as an artist, each viewer interprets and experiences each work differently from the other. But, to “touch the audience is what artists are dreaming of.” Truly one of the most important artists of our time.

Whilst in Versailles, Champ Editor Joanna Kawecki spoke with Ufan on his artwork, art criticism, and thoughts on mono-ha today.

Blue is the most distant colour. Difficult to reach as the sky. Containing both life and death. It is the colour of nothingness.

JK: Each artist or creator has a sense of hope to influence or inspire their observer. Do you have a main aim of your artwork (paintings / sculptures / installation), for your viewers?

LEE UFAN: It is first, because I want to realise an artwork by myself that I work. Then, I want the viewers to encounter my works, but even though my works are related to me, they are already an open world which is out of me. That is why the encounter is different depending on the viewers. But to touch the audience is what artists are dreaming of.

JK: How did your Korean background and upbringing in Japan shape your personal perspective, and then in turn, influence your art?

UFAN: I was born and raised in South Korea and received education in Japan, and I think I learned from South Korea the atmosphere of the peninsula, the ever-changing ups and downs of history, and from Japan; purity and formal beauty. There are some geo-political differences, but in a larger scale, there is the specific spirit of vanity of monsoon regions that composes my expression.

In general, I think that the idea in Europe is to grant an unchangeable value in being and making, whereas in Asia, variability: connections, the fact that one day things will scatter and disappear, is valued. Nevertheless, globalism due to the suddenly changing civilisation causes more diverse imagination that goes beyond the regional differences of culture.

JK: Why did you feel drawn to write your own art criticism at the time?

UFAN: At the end of the sixties, as there was no art critic who understood Mono-ha, I ended up writing art criticisms. However little by little, my writing were more like thoughts. I’ve always been someone who had a strong reflective point of view. So I thought contemporary art was too much inclined to a capitalist production system and that is why I emphasise on trying to question the origin of expression.

Now is the time to ask ourselves: Where does the expression begin?

JK: Do you believe different mediums such as sculpture, paintings, sketches, all share the same dialogue, and does each have a potential to set off a vibration for emotion, connectivity, imagination?

UFAN: The sensation of art, even if it is from the same artist, changes a little bit according to the mean of expression. As the material and form change, it inevitably arouses another imagination. However whatever mean you choose, the fact that an artwork is a medium which moves the viewer re- mains the same.

Compared to modernism which delivers the artist’s ideology as it is, Mono-ha brings external non-artistic elements like material, space, air, etc. making viewers to participate. Joining the made and the unmade is the issue of Mono-ha.

JK: But what is the true translation for ‘mono-ha’, and your personal explanation for this term? Has your perspective on the movement changed or grown over time since establishing the concept?

Mono-ha is translated by “school of thing” and mono, “thing“, connotes the meaning of a substance which is unmade. Nobody established this concept, the word Mono-ha came after artists who were jeered because they irresponsibly brought unmade objects into their expression. Thus there was a misunderstanding that Mono-ha insisted on mono, but the truth is Mono-ha artists are not interested in the mono, “thing”, itself, they brought up the problem about supporting modernism while accepting external elements.

JK: The Lee Ufan Museum in Naoshima, is a permanent reflection and presentation of the philosophy of your works located in a secluded area of the island. What first drew you to the island, and how did you come to work with architect Tadao Ando on the design?

UFAN: My work even if it’s the same one, has the characteristics of looking different depending on the place. It is because space, location, and background are part of the work. Tadao Ando is an old friend who I trust. I have always wanted to work with him one day. As we found the place for the museum together and that we shared the concept of a space looking like a cave, the museum was built very naturally.

JK: Another remarkable location is Versailles. Can you explain how to approach presenting work at such a visually distinctive location such as Versailles. It is not the usual white walls, or minimalist space of nature. How have you worked together with curator (and Director of Pompidou Centre, Paris) Alfred Pacquement, for the composition of your works in Versailles?

UFAN: Versailles is a very historical place and especially the garden which is a special architectural space designed by André le Nôtre. I neither wanted to rationalise it, nor ignore it. Discussing with Alfred Pacquement, I learned that the creation of the space had a complicated history and was based on a precise garden concept, so a lot of elements from nature or space were hidden. So I have to express the Mono-ha phenomenon or power that nature or space initially have through installations. Using natural stones that we see anytime anywhere, and deriving from it, iron steel or stainless steel produced by our industrial society, I proposed an extremely simple and neutral structure in order to show the space in Versailles is infinitely open.

This article was originally published in Ala Champ Issue 9.