KOICHI IO

A Tokyo Studio Visit to the Third-Generation Metalsmith & Contemporary Artist

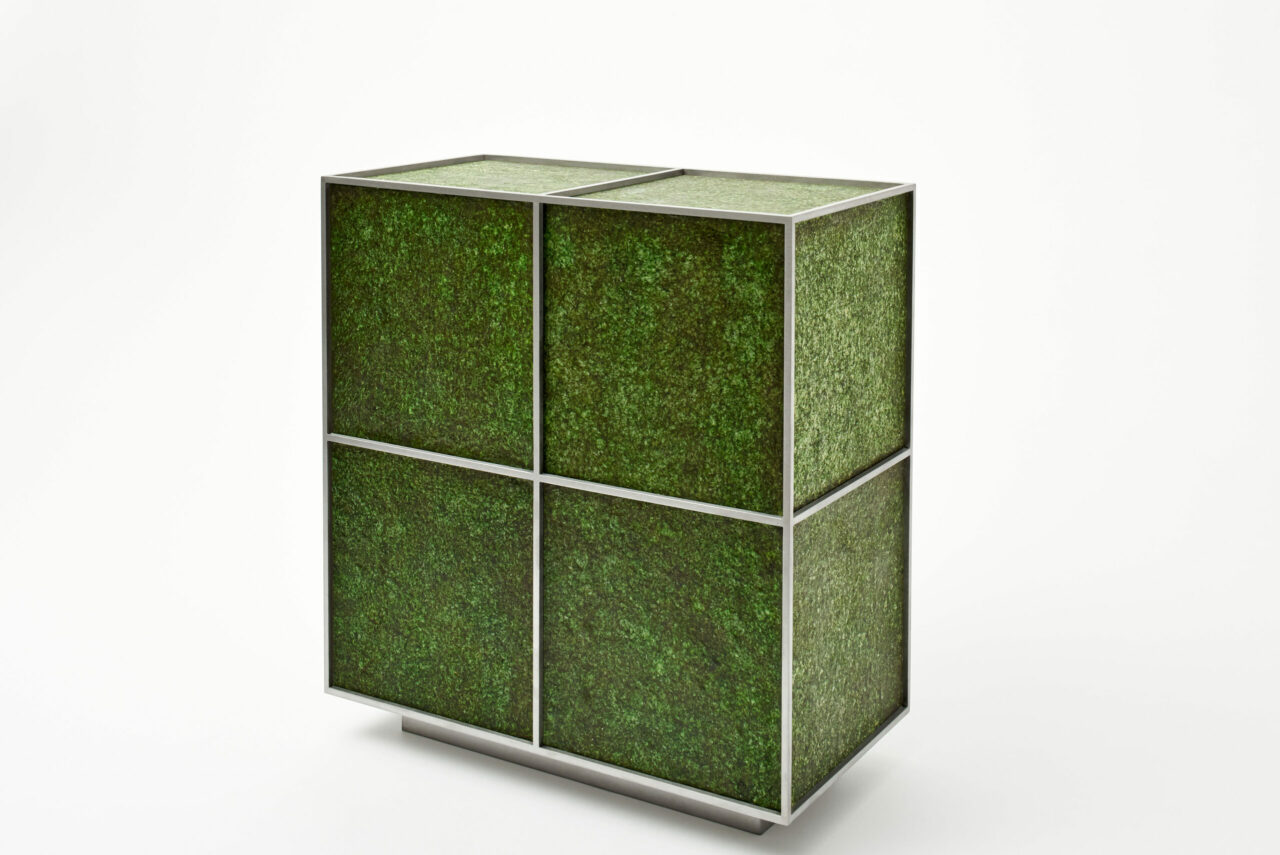

In the unassuming back streets of Aoyama, Tokyo’s luxury retail district, find metalsmith Koichi Io pensively working by his large, central studio table. With worn-in depressions and lacquer markings embedded across the timber, the table reveals the laborious skill required to create each of Koichi’s unique and one-of-a-kind works. As a contemporary artist, Koichi’s hand-battered metal works are akin to fluid forms found in nature. Whilst they may appear light and simple, they are the exact opposite — their arduous composition is only made possible by a trained hand and a wealth of generational knowledge.

At just 35 years of age, Koichi is the third generation of a family of traditional metal smiths, following his grandfather and father Kenji who had established the Aoyama studio now 40 years ago, and who also remain highly regarded for their metal artistry. In the second-floor workshop, Koichi sits alongside Kenji who continues to work to this day, and also shares the studio with his partner, contemporary jeweller Mariko Sumioka.

Surrounded by various hammers, tools and patination samples, Koichi’s pieces begins from a single sketch, often influenced by the neighborhood’s contemporary art and architecture that Koichi witnesses whilst on his way to the studio. Tokyo-based Champ Editor Joanna Kawecki met with Koichi at his Aoyama studio to get to know more about the intricacies of his craft and trajectory as a fine artist. For those who may be in London, his works are currently on view at the ‘Metalworking Now’ exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Ala Champ: As a third-generation metalsmith, what sparked your initial interest towards continuing this craft and did you feel a responsibility of your family to continue the skill?

Koichi Io: My name Koichi (鉱一) means “first son of metalsmith”. My father and grandfather obviously had expectations, but I felt I didn’t see becoming a maker like them since I was a child. Of course, I always had the dilemma of how I could deal with all the remaining tools and studio if I didn’t [choose that path], but being in that circumstance was just too natural for me and I couldn’t feel any special encounter with a maker’s world. So initially, at art college my first Major was in Art Management and Administration. Yet even then, I didn’t imagine becoming a maker. I started my training after entering college and slowly started to be fascinated by this circumstance.

We are currently standing in your studio in Aoyama in central Tokyo. How does being situated right in the heart of the city inspire you?

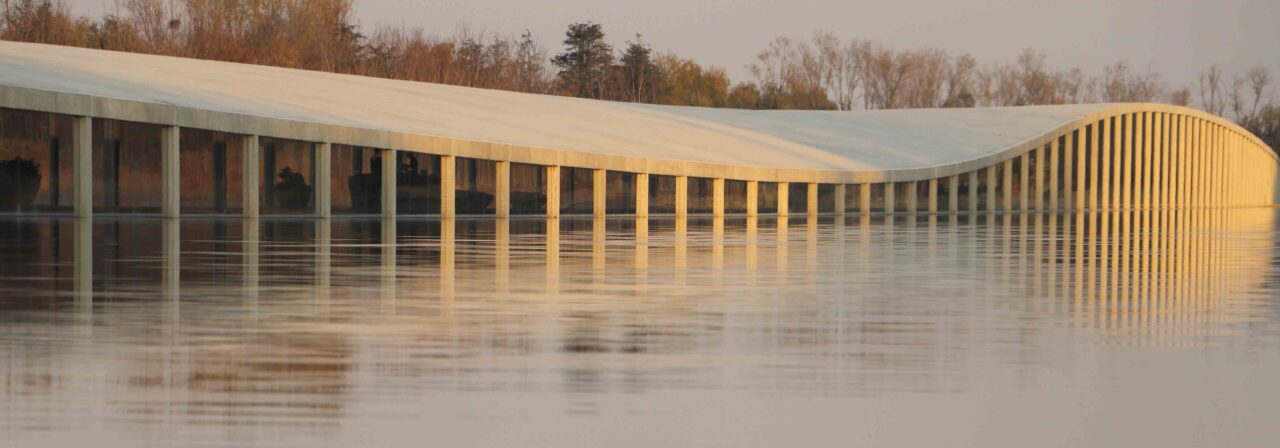

Aoyama is known as a fashion and design street where many flagship brands and galleries exist. I especially love both modern and contemporary architecture on my way to the studio. I adored the old Aoyama Dojunkai apartment and contemporary buildings by Toyo Ito, Kengo Kuma, Tadao Ando, and Herzog & de Meuron always inspire me. As [my father and I] have nothing to do with the regional craft industry, Aoyama is a place where we can work as individual artists.

Your handcrafted vessels are the result of laborious skill, yet have a harmonious, natural beauty. How do you determine the form you will create, or is it made spontaneously?

My biggest interest in working with sheet metal and hammer-raising methods is to see how metal changes form with the tools and my labour. And each metal shows me different faces which are also very exciting. I am always excited when I start new work like “what can I do with this material….” Before I start making, I do drawings and calculate the size of materials I need. I also make a paper gauge as a base form. However, these are not for making the exact form as I plan, but simply to visualize my idea to 3D image. The deep interaction between material, tools, and my conscious is more important after I start making. The resulting form is the consequence of negotiations between them.

What are the main metals you are working with?

I’m working with copper, silver, iron, and traditional alloys called Shakudo (copper-gold alloy) and Shibuichi (copper-silver alloy). Each metal has different characteristics and I am always fascinated by how they react in my hands differently.

What are some of the best memories you hold from growing up in a metalworking family and learning skills from your father?

My grandfather passed away when I was 7. (We actually had the same birthday and he passed away a day after our birthday…Such a happy life.) So I have never [directly] learnt from him but I can learn something whenever I use the tools he left. Also, I can never forget the moment at the studio when I started my training under my father. I was struggling with hammering copper which was like iron for me. Then, my father showed me how to do it. The same copper looked like velvet in his hands. I think these moments show how we can share and inherit tacit knowledge through studio practices.

What were the key lessons that you learnt from studying metalwork at Musashino Art University, that differed from the history and traditional lessons from your father?

My first Major in Art Management and Administration became a great help in how I approached the art market. It may sound odd, but what I learnt after changing my major to metalwork was that you didn’t have to make it your job just because your major is metalwork. Growing up in a family of makers, I was sort of blind about that. At the same time, that idea made me realise how lucky I am to have my background.

Being awarded your first prize at such a young age of 22, how did that motivate or inspire you to continue your craft?

That experience opened the door to my career as a maker. I understand that was sort of beginner’s luck but the prize gave me an opportunity to MA study at Seoul National University. My 3 years of study there allowed me to reach more international fields and made me who I am now.

How do you feel traditional Japanese craftsmanship made by hand can remain relevant in the future?

I think preserving skills is not a purpose. If we can exist in the future, it is the consequence of our pursuit in redefining ourselves in a cultural context. For example, I do teaching twice a week in our studio and I found that our students’ motivation is changing over the decade. They expect an experience more physically at the studio. It may be because many jobs are replaced by technology and more difficult to feel “real” in their work. This shows our studio practice might include more values that haven’t been recognised in the past. I hope we can find more new values and perspectives within us and share them with people.

Finally, what are you currently working on, and what news do you have to share for the coming year?

I’m working on iron pieces for the last couple of months. Two of them will be shown at TEFAT Maastricht with Adrian Sassoon Gallery for the first time in March. The other one will be at Galerie Handwerk in Munich also in the same month. Currently, my copper piece is exhibited as a part of ‘Metalworking Now’ at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London until 31 August, 2023. Hope you will have a chance to visit them.

Koichi Io Studio Visit

Location: Aoyama, Tokyo

Images & Interview: Joanna Kawecki