FEDERICO PESTILLI

A Tribute to our Vanishing World Through the Eyes of this Italian Photographic Artist

Currently based out of his father’s hometown of the Apennine mountains, Italian photographic artist Federico Pestilli has been on the move for a large majority of the last decade. From Paris and London to the most beautiful locations in Africa, the 35-year-old photographer’s studies and life’s work have taken him to both densely-populated cities and the remotest of locations.

With his work ranging in subject matter, Pestilli’s documentary-style photography points a direct lens on the world around us.

Born and raised in Rome, Pestilli moved to Paris in 2004 to study at the Sorbonne, where he completed a Master’s in Arts History. His desire to learn then seduced him to New York where he went on to work in creative agencies and renowned stylists, later moving to London and assisting renowned photographer David Sims. From this gathered experience, Pestilli continued to develop his work through creating visual content for commercial and non-commercial projects. In 2013 however, he changed course and went on to volunteer in a scientific research facility in the Brazilian Atlantic forest. Straight-forward about his interest to abandon the fashion industry and pursue an honest direction guided by his artistic expression, he has been travelling ever since.

“When I was younger I had a passion for wildlife and wanted to work for National Geographic, travel the world and spend time besides other living beings. I always hoped to do something to protect the natural world I loved so much” Pestilli explains. Certainly following this ambition, Pestilli’s work has led him to every part of the globe. From documenting scenes and moments all over the world – from Mongolia to Equador and sub-saharan Africa, Pestilli has a particular soft spot for the African continent. “I love its climate, wildlife and natural landscapes. The people in the most remote places belong to cultures which have remained mostly unchanged for thousands of years. To visit them means to time travel, to get to know confront yourself with ancient, medieval, and modern times. It’s all there”. With a visually subtle yet powerful individuality that exists in Pestilli’s photographs one constant remains: his desire to justly and accurately portray the character of his chosen subjects.

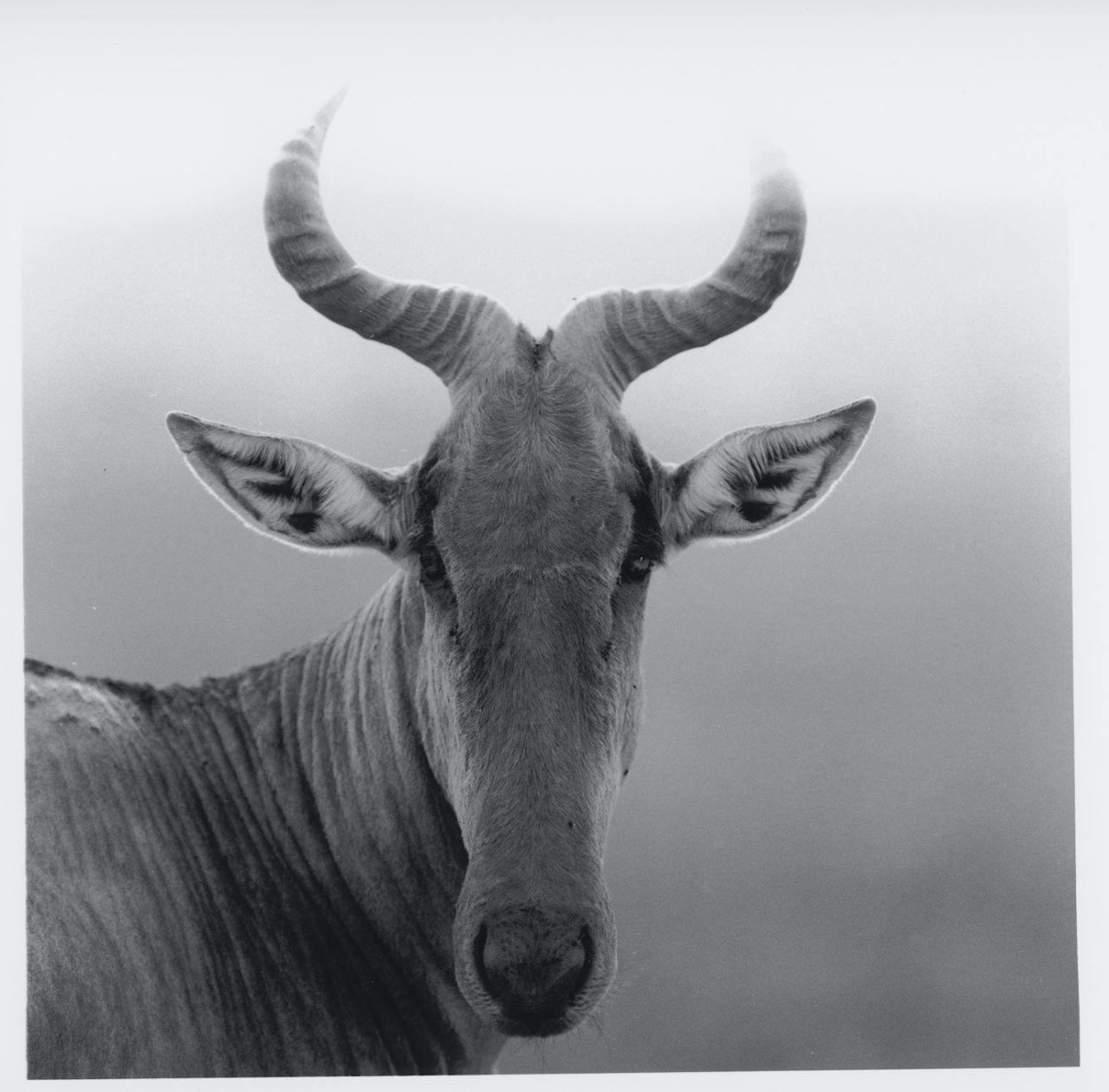

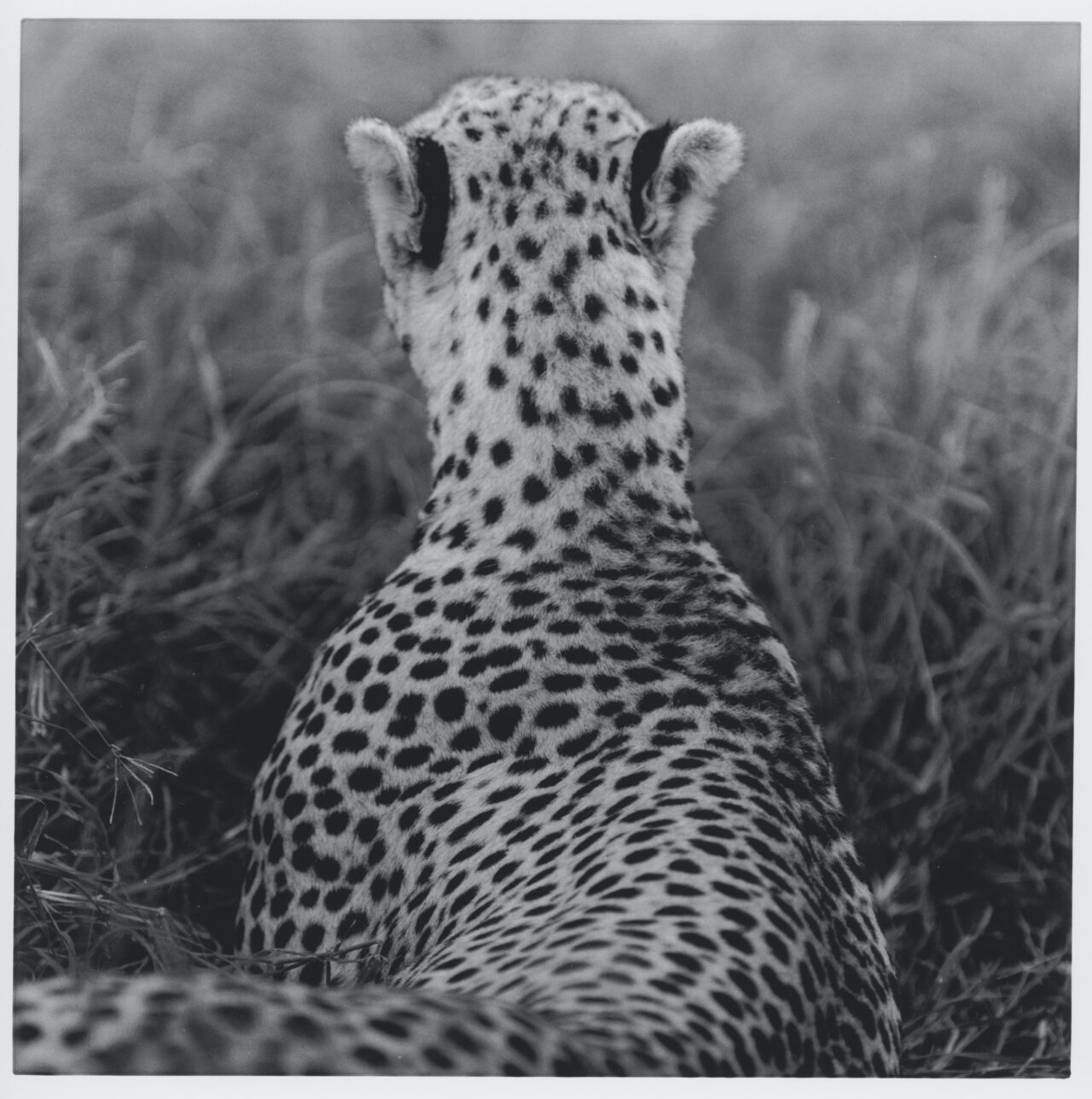

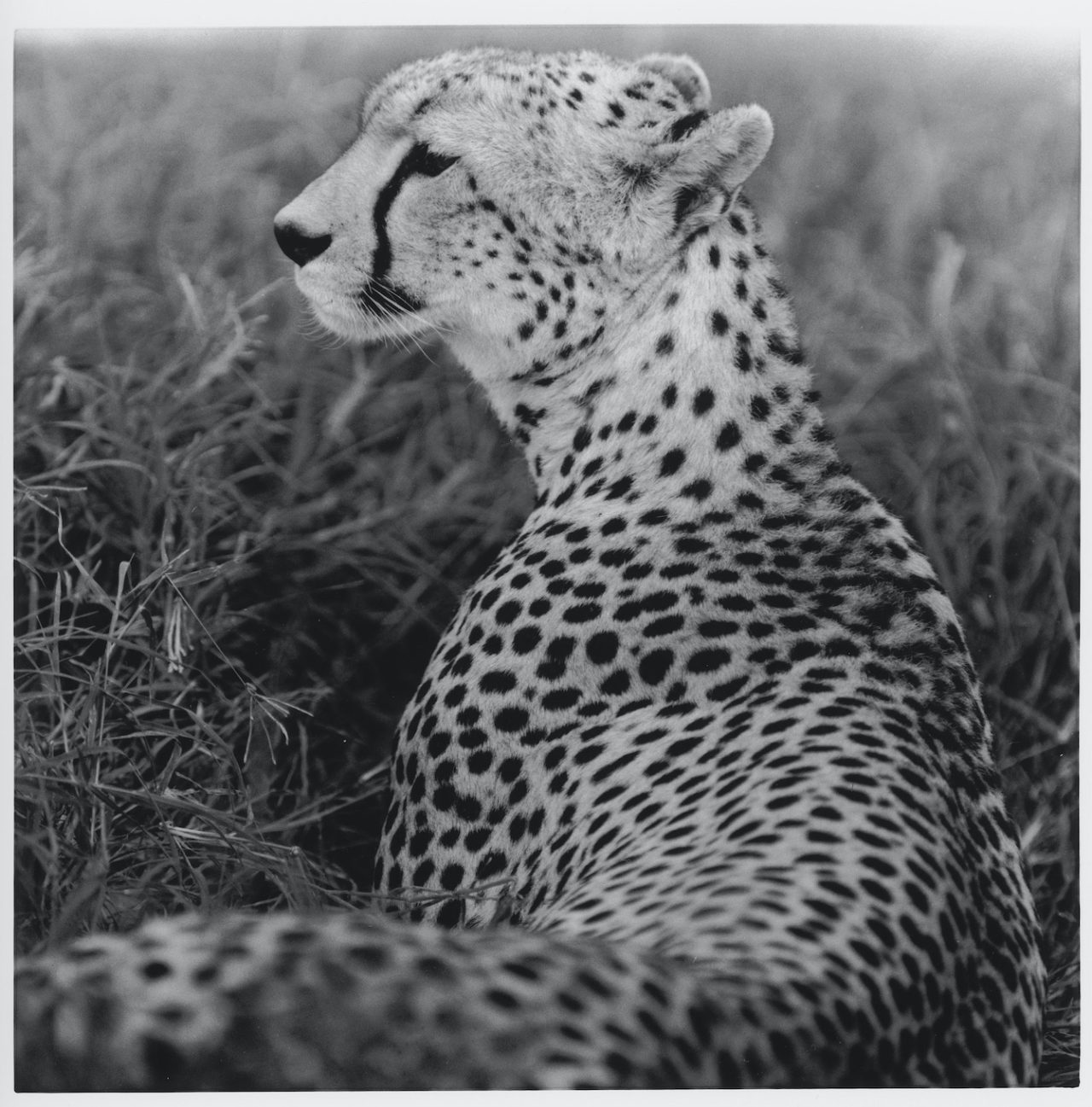

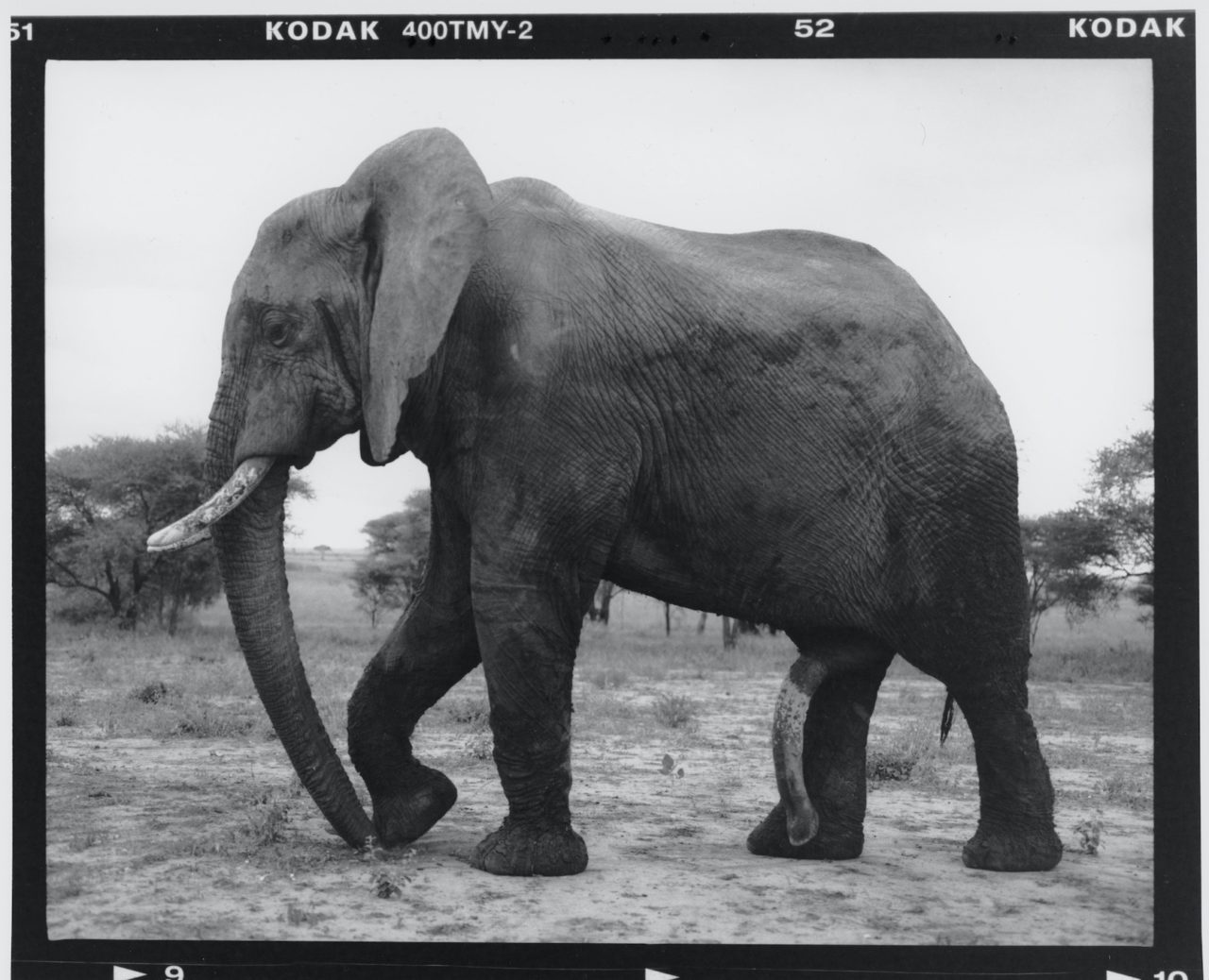

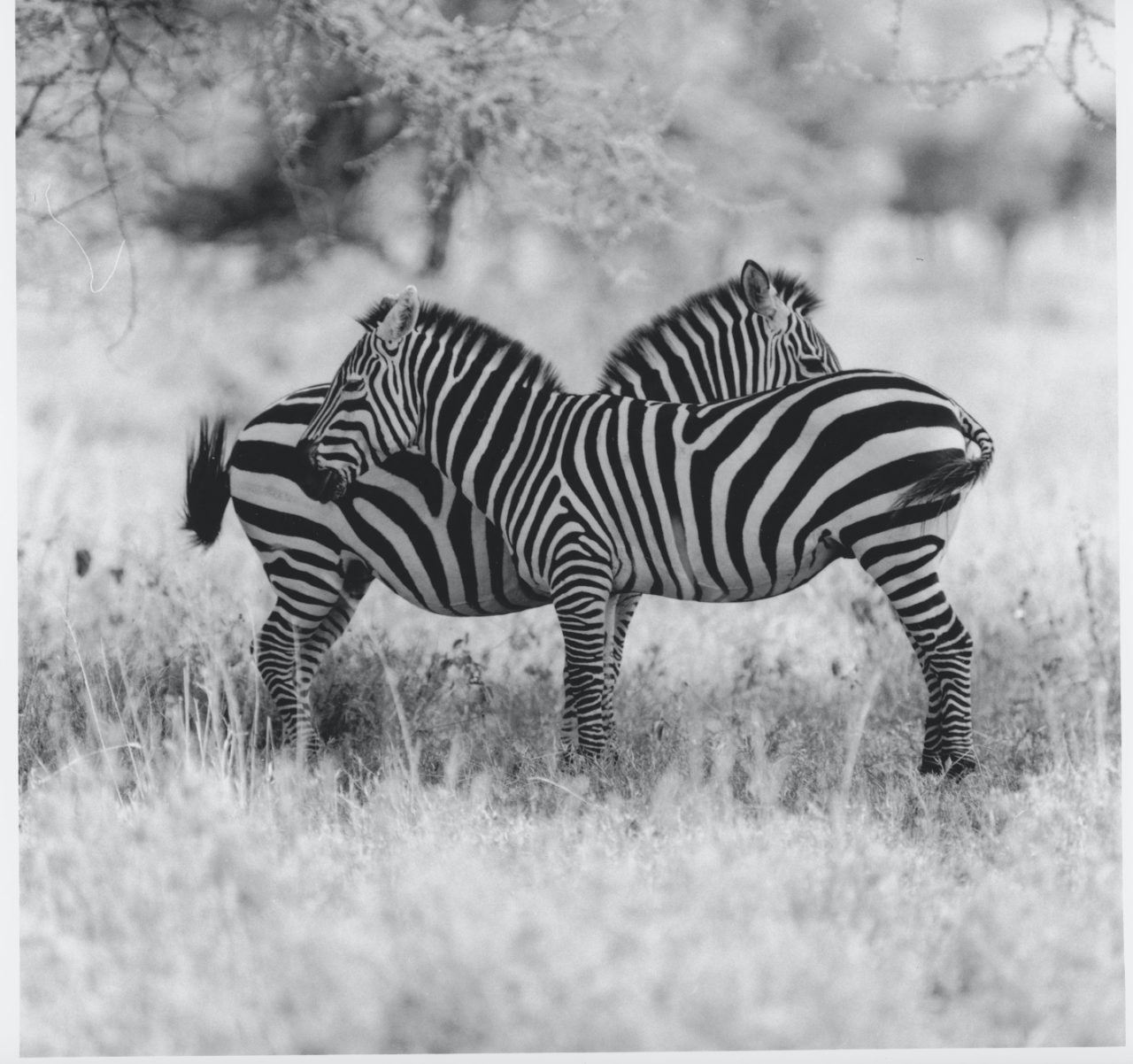

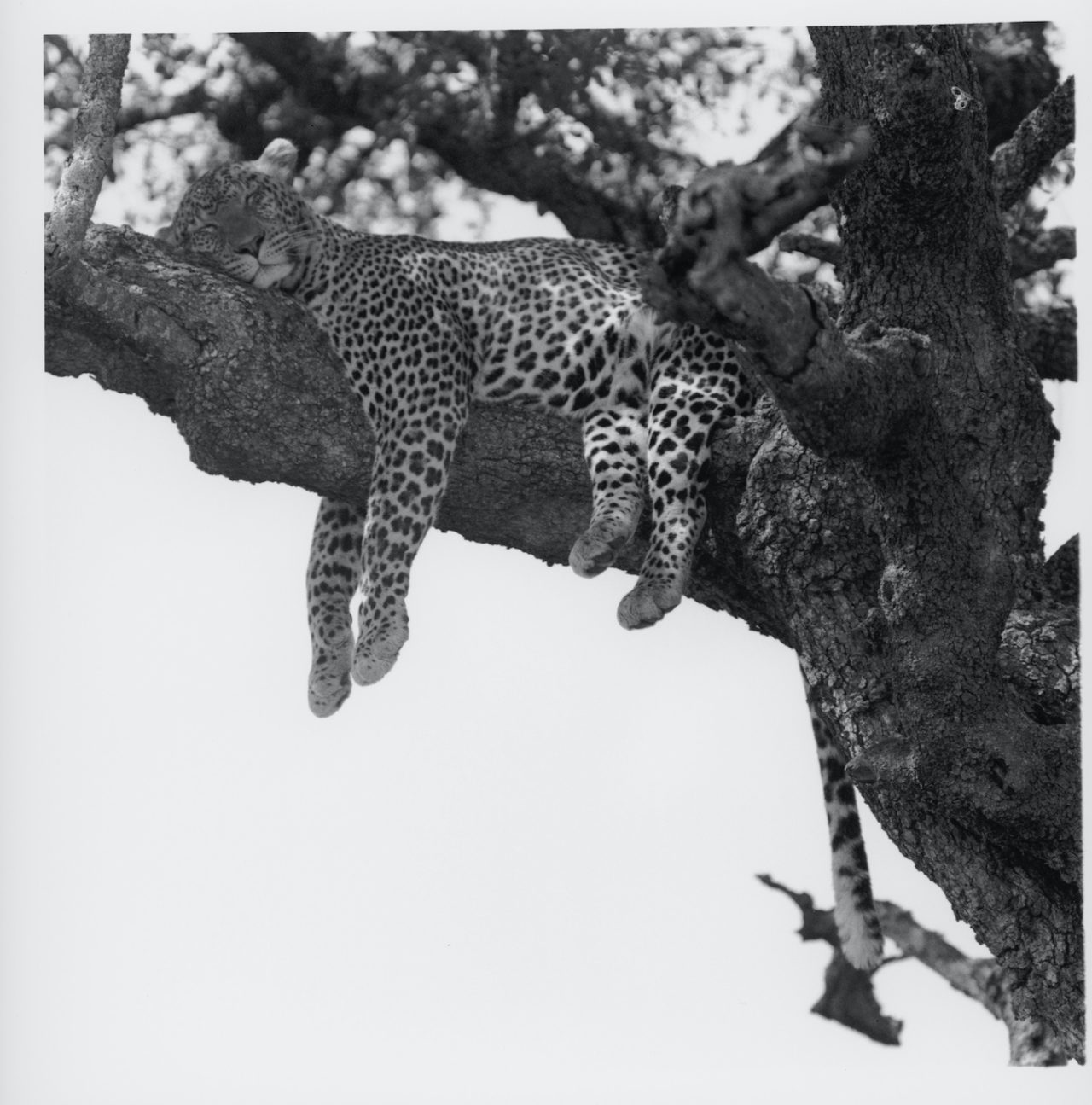

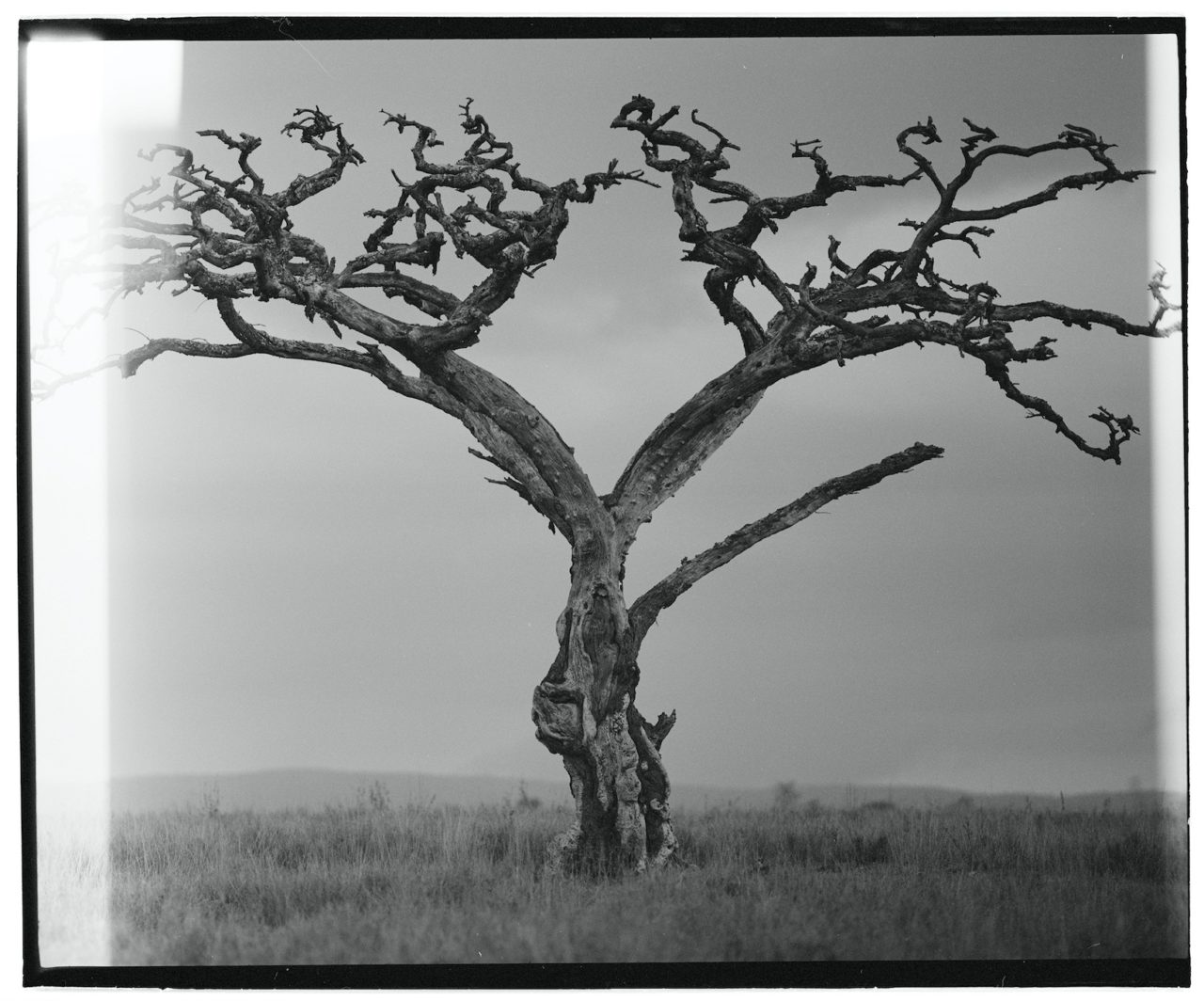

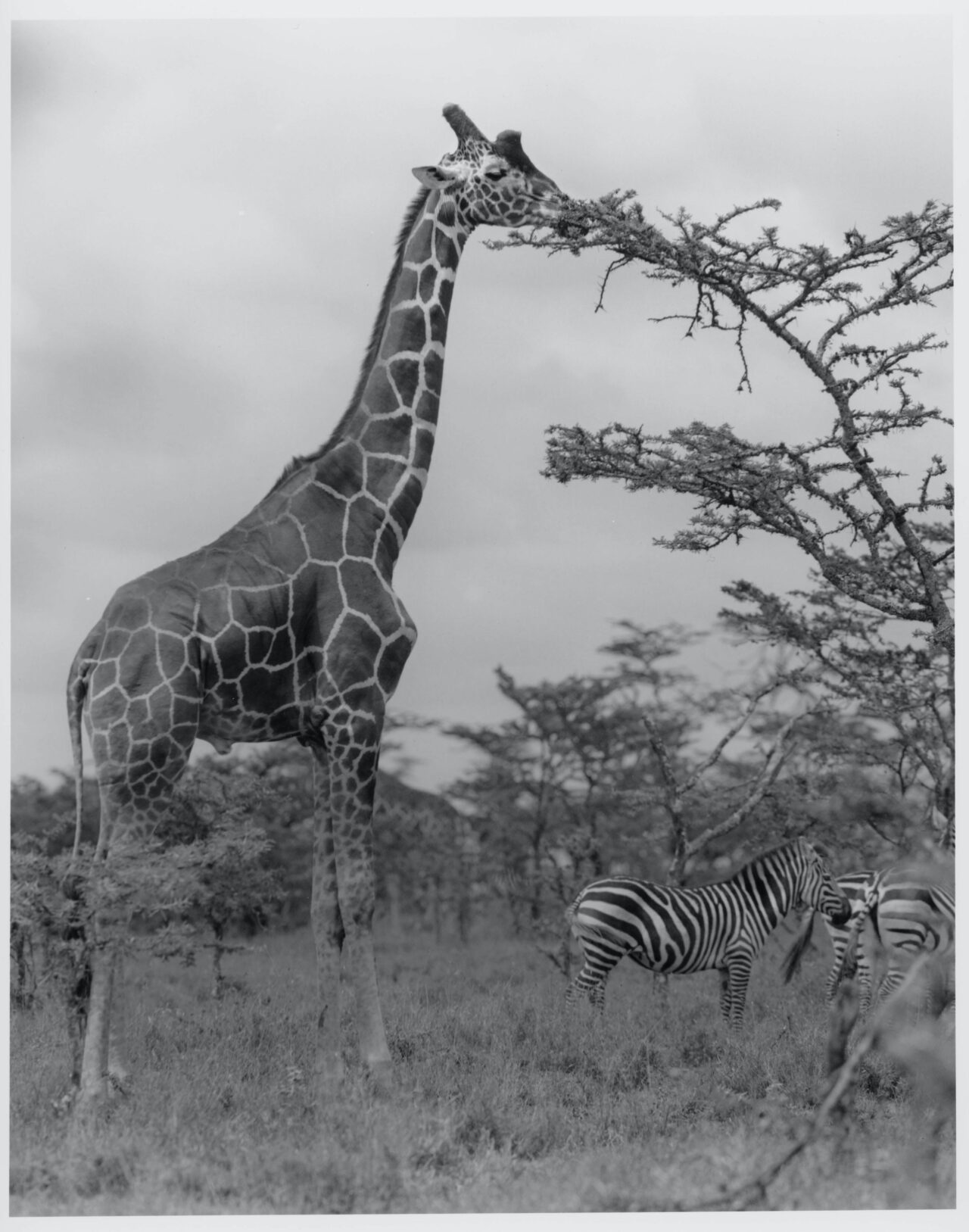

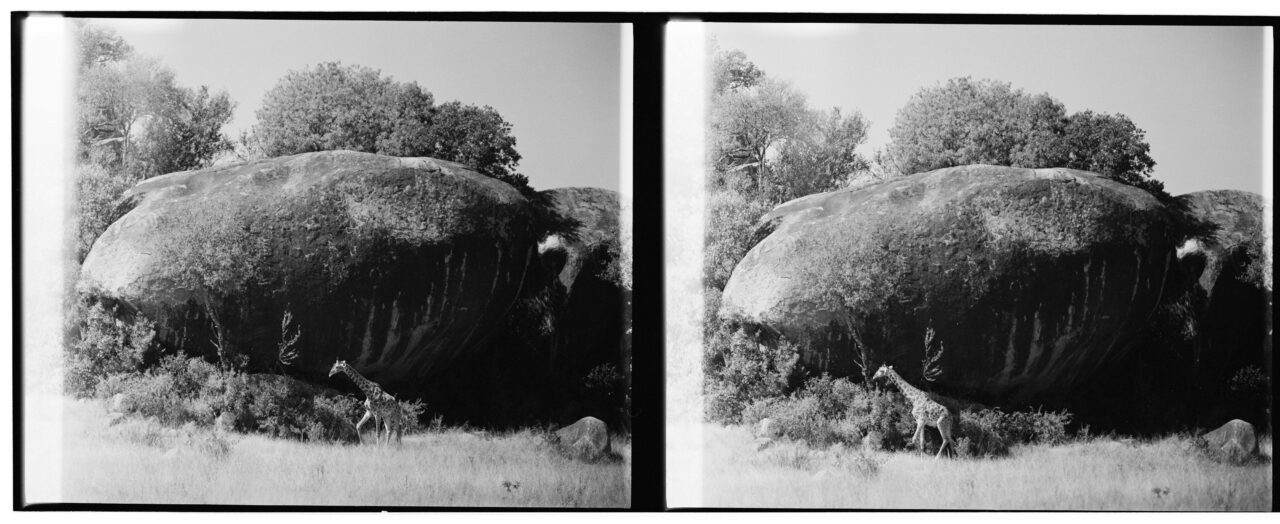

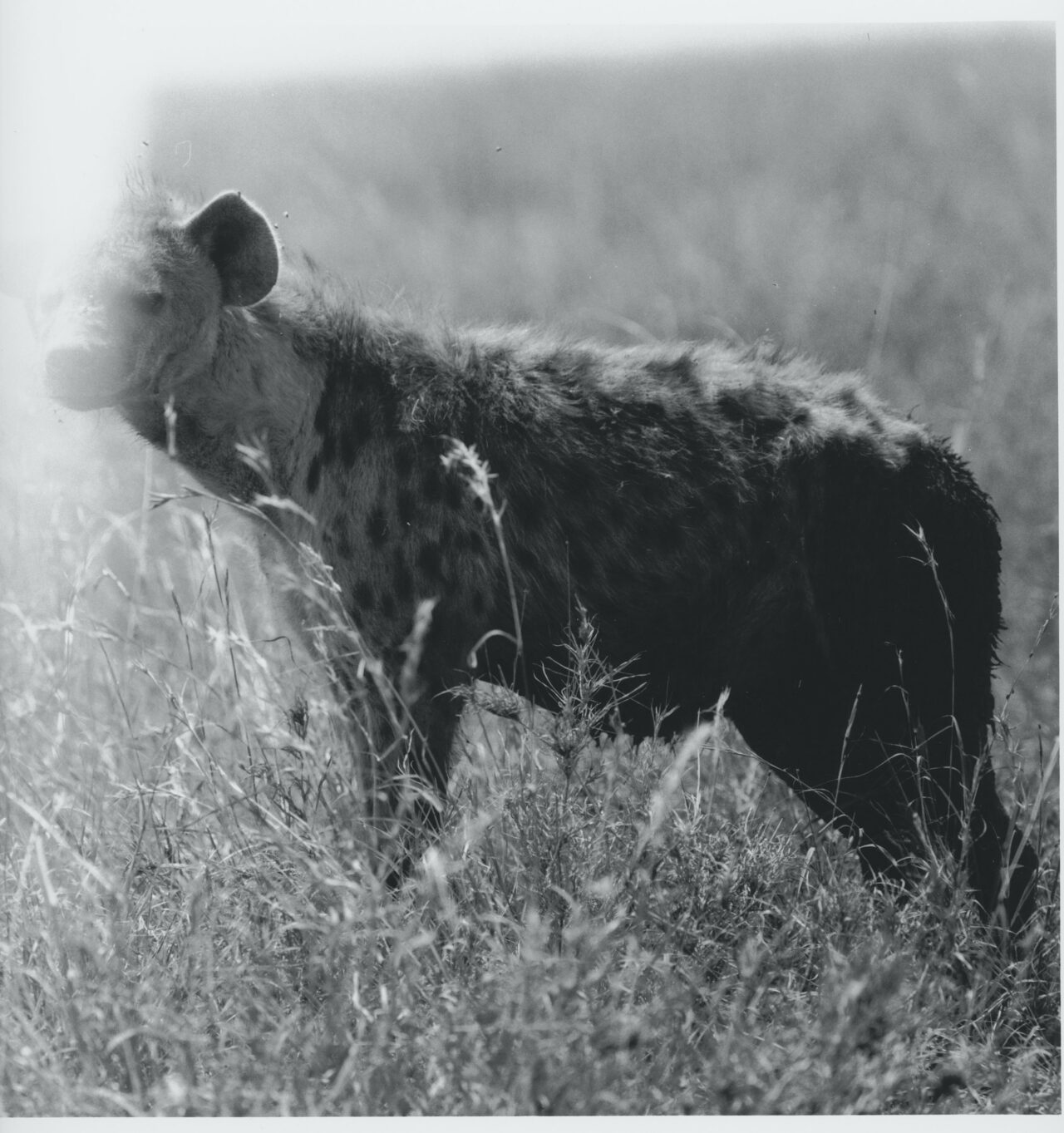

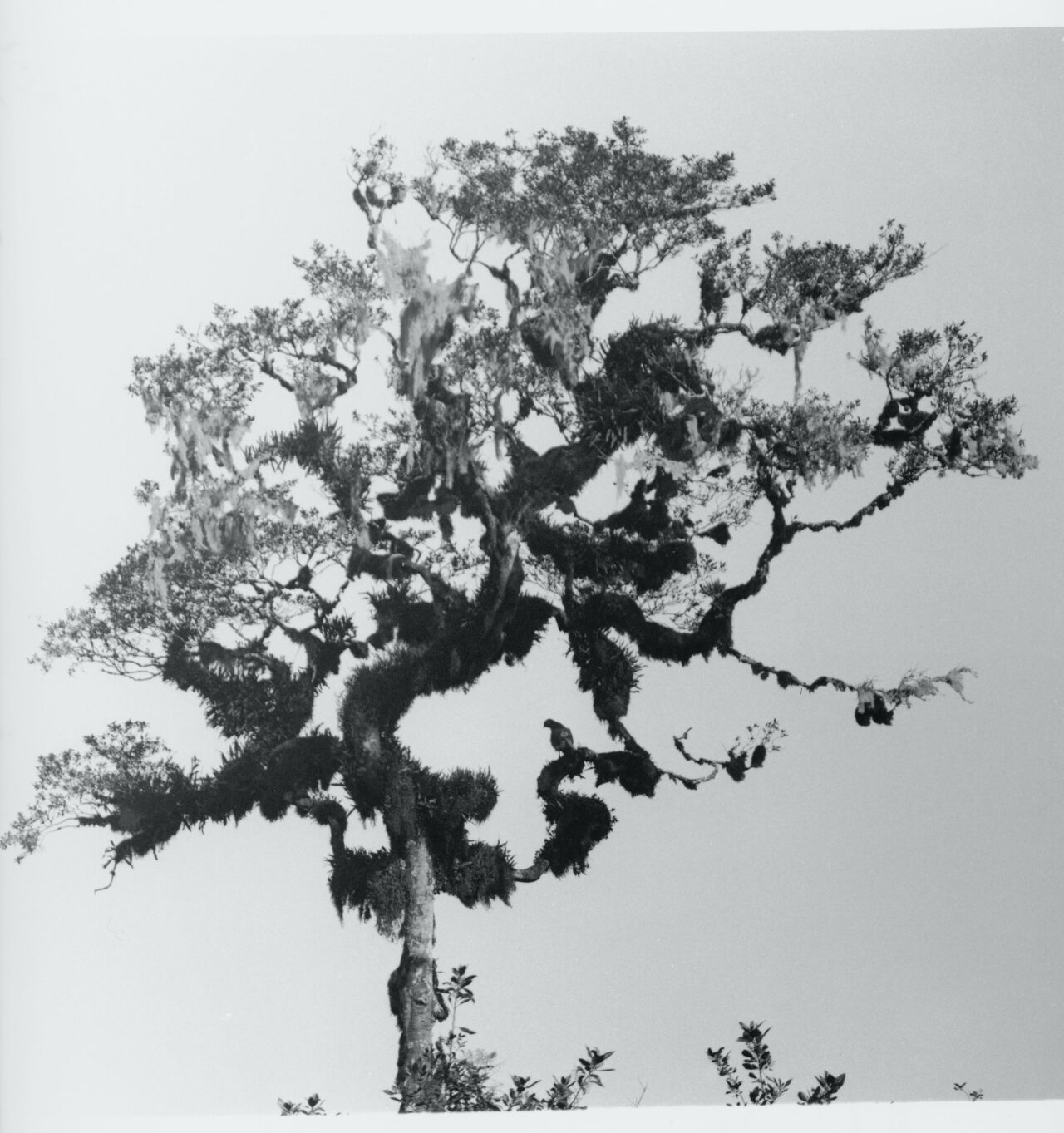

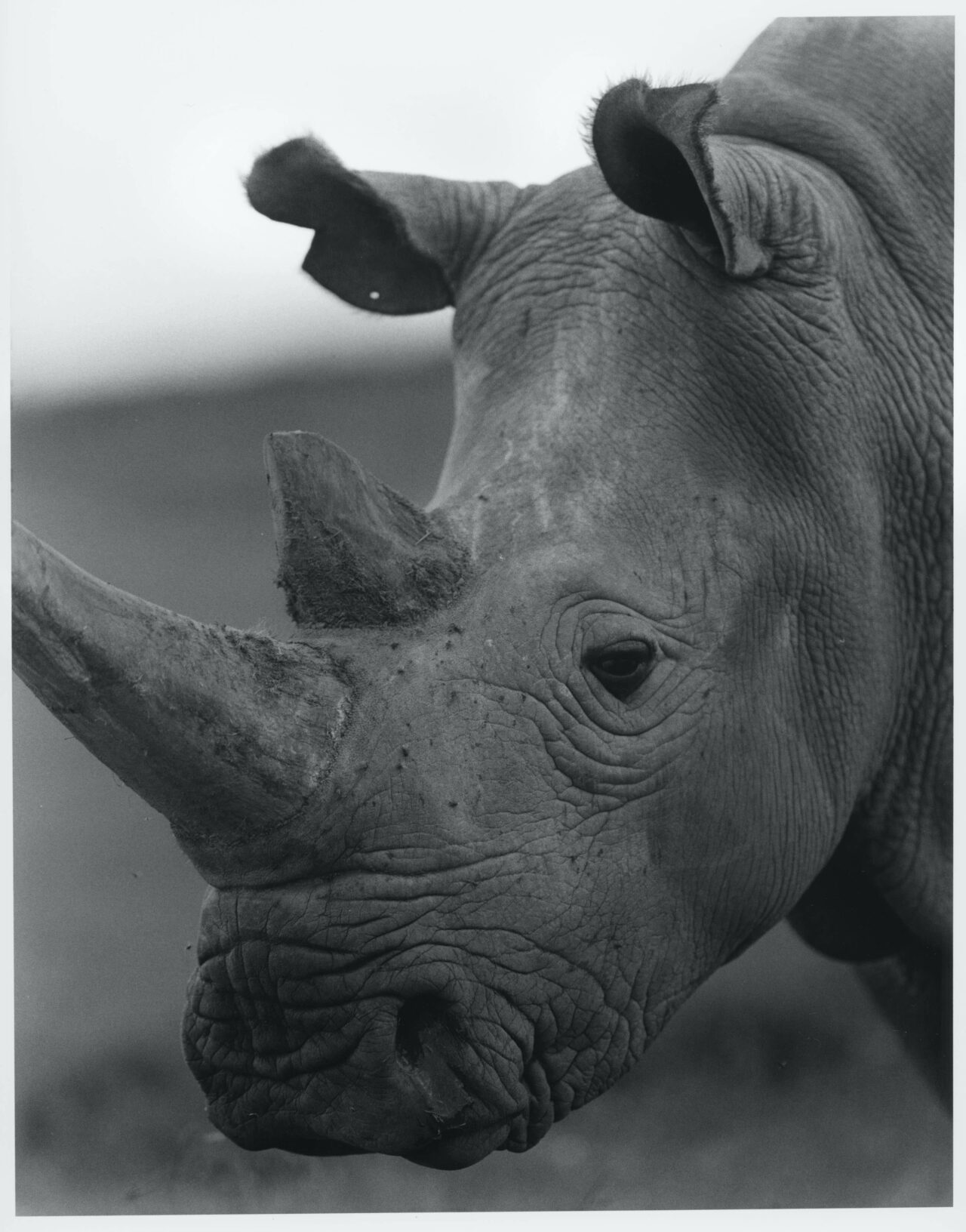

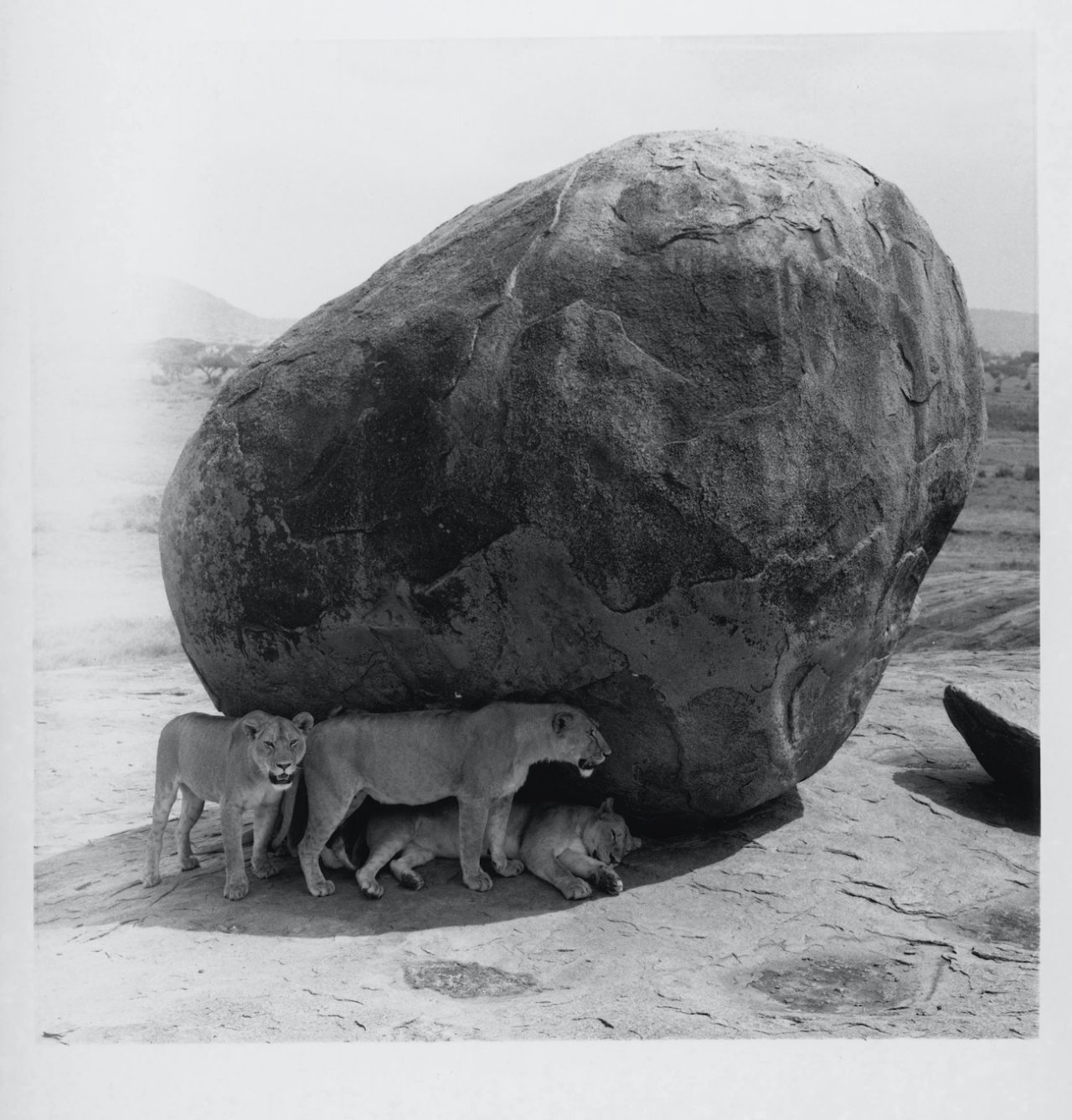

In his Extinct series, Pestilli showcases our planet’s beauty and strength but at the same time its ever-growing vulnerability. “Just as photographs can fade over time, so many species on our planet are permanently fading from view”. The images in this series are dream-like, highlighting the uncontrollable beauty of the photographic art form when explored with the right tools. In Extinct, Pestilli would wait out hours in the wilderness to capture the right moment in herd migration or a reclusive’s animal’s daily movement. Further exploring different mediums, camera traps were used in not only in this series (to capture black rhino gathering at a watering hole) but also in his upcoming Heritage body of work (to document packs of wolves in the mountains of Abruzzo). Using film photography for this series, the medium highlights the urgency to protect our surrounding environment, reminding us to take action for all that we have to lose.

We spoke to Pestilli during the lockdown in Italy to find out more about his life’s journey, current motivations and what may lie ahead for him and his work in a post-pandemic world.

Was there a significant turning point for you and your photography work?

There were and will be many significant moments in the process of self-realisation and self-awareness, however if I were to pick a specific turning point, it would be when I decided to leave London and abandon the idea of a career in the fashion industry. I realised that my freedom of expression was not being recognised within the industry, that behind the constant talk about creative freedom and artistic expression were really a strict series of parameters which either included or excluded you from what is considered “good”, “cool”, or “beyond”. To do fashion essentially means to sell a consumable good. If you’re not selling, it’s not good. This also applies to a natural portrait, where you sell a standard of beauty, hair style, skin texture… it has to fit within the industry or speak about it.

I left London in 2016 and went to do volunteer work in a scientific research facility in the Brazilian Atlantic forest. I have been travelling ever since, taking images which aim to only sell thin air: my thoughts.

What are some of the challenges you face in your work?

I would hope that my challenges are the same as anyone’s who is keen on producing something of true artistic value to society. By “value” I exclude monetary value. I think you can be lucky to make money with art in your career, but really profitable artwork usually excludes the artistic process. For me value is based on emotion and virtue: what is your message and how compelling is it?

Personally I have completely separated the process of making a living and photographing. Both are necessary but by separating the two I have definitely given my creative work wings.

Where are you right now, and what does a typical day look like for you?

I am spending the Summer in the Apennine mountains, in a town where my father’s family is originally from. A typical day here involves early morning hikes up in the mountains to check on wildlife camera traps, then I spend the rest of the day looking for interesting subjects to photograph. I am trying to portray the land in it’s most intimate aspects, from still-life images of waterfalls and canyons to portraits of shepherds out at pasture.

What tools do you use every day?

My eyes! I have never been a decent musician, my sense of timing is poor. Instead I have always relied heavily on my sight for everything. Visual memory. If you tell me a phone number by voice I’ll never remember it, show me on paper and I will. It’s always been this way for me.

I am not tied down to specific tools. I think the tools are part of the message and depending on that I’ll adapt the tools. An image shot on analogue film has a completely different message from an image shot on a cell phone. The value of either depends on the message. I definitely use my phone as a daily recording tool. I think the images I take daily with it will reveal their inherent value in time, I am still feeling out my reactions to these images. For example they are incredibly effective for Instagram stories, they bring a sense of realism and spontaneity which an image from a professional camera would exclude at the get go.

Can you tell us more about your Extinct series?

The Extinct series is full of personal meanings for me. When I was younger I had a passion for wildlife and wanted to work for National Geographic, travel the world and spend time besides other living beings. I always hoped to do something to protect the natural world I loved so much. The title ‘Extinct’ is meant to make us cringe at the idea that the animals portrayed may be already extinct. Of course this is not yet a reality but may soon be one with the accelerating climate crises.

I am shooting this body of work using black and white film in an effort to make the photographs look like the images we have of creatures which are already extinct, such as the Tasmanian tiger. In this way the images aim to be a testament to posterity of the beauty which roams our planet today. The greater part of the series is shot in East Africa (Tanzania and Kenya). The creatures and landscapes in this part of the globe have always fascinated me. The idea of losing iconic species such as the lion, elephant, or rhino is just heartbreaking. By securing landscapes for these larger animals the future of other species, small and large, will also be protected.

In the Extinct series, what are some of your favourite images and can you tell us about any of them in particular/which have a special story?

Many images from the series are charged with meaning for me. I often had to wait many hours besides the animals, return over multiple days to the sites where they roamed, and get to know their landscapes. So every image has a story behind it where the essence of the animal portrayed really became part of me, for example in the case of the image of lions under a boulder in the Serengeti. Early one morning I went to this particular kopje to photograph the boulders. As I was about to jump out of my vehicle I realised a pride of five lionesses were sleeping in the shade of a massive stone. I consequently spent the entire day next to them, having lunch and sleeping in my land cruiser, waiting for the lioness to become active. By evening they started to awake, stretching and looking about, getting ready for the night hunt. It was a magical day spent besides the lions.

Another image which comes to mind is of the zebra migration. Thousands of zebra formed a queue which moved out into the landscape and this was a difficult image to render without taking it from the sky. Their gradual congregating under a large dead tree gave me the opportunity to show the scale of their number and their size.

I also think of an image I took with a camera trap of black rhino coming to a watering hole for a drink at night. In this case I was fortunate to photograph two rhino together, and a turtle also popped into frame to participate in this unusual insight into nocturnal life. The thrill of camera traps is that there is a great percentage of randomness is how the animals will enter the frame, thus making the images more exciting.

What are you working on currently / upcoming projects?

As time goes on I continue working on all the projects I have worked on previously. All projects seem to feed the ones to come. I am currently working on a project called Heritage, focusing on the roots of my family’s past in the Italian region of Abruzzo. This body of work is still taking shape, however I would like it to feel like a mosaic of imagery expressing the richness of the land my family is originally from in an intimate way.

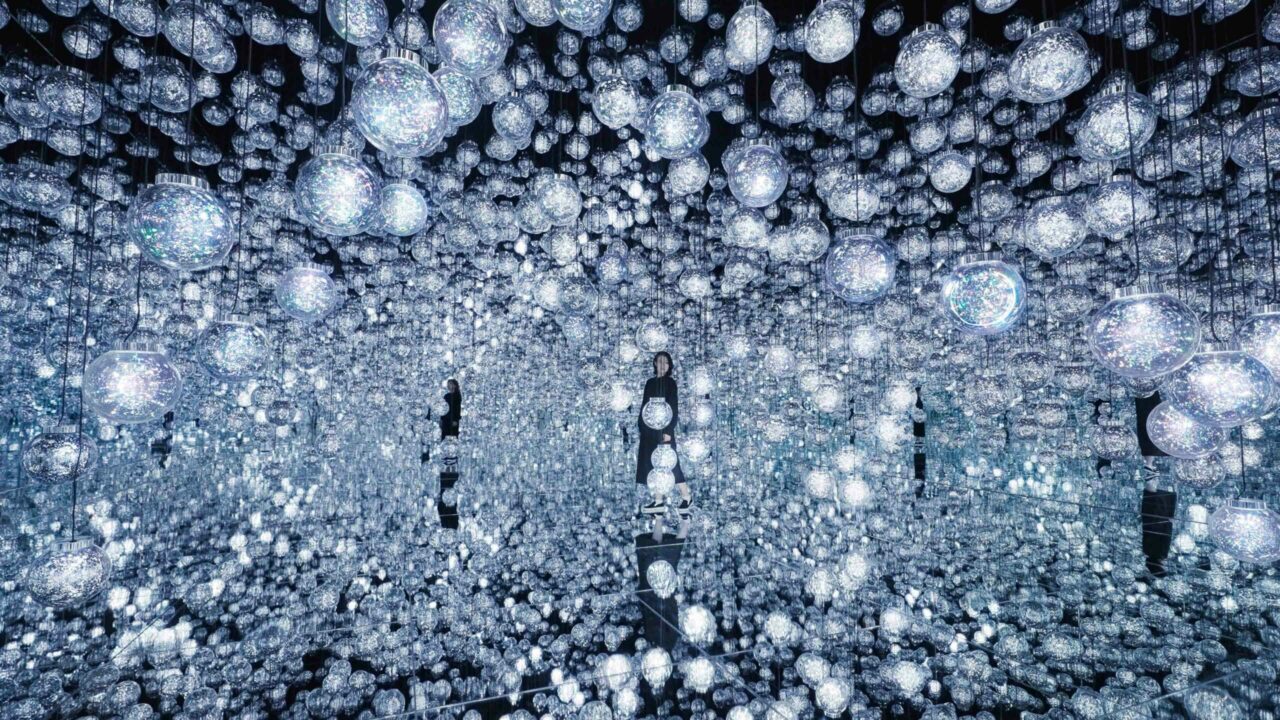

While working on this project I keep working on the Travel imagery, on the cell phone diaries, and when I’m back home on more abstract fine-art work which includes painting on photographic prints.

Given the COVID-19 lockdown I’m not sure how soon I will be able to travel far from home. I will most likely continue working on Heritage, camera trapping wolves in the Apennine mountains and taking portraits of people still employed in trades of the past.

∆

Photography: Federico Pestilli

Introduction: Monique Kawecki

————-

Discover the artist’s latest projects here