DIRECTOR SERIES: JAKE MEGINSKY

Hailing From A Small Town In Massachusetts, We Speak To The Producer, Percussionist And Now Director About His First Feature Length Documentary: Milford Graves Full Mantis

Musician and producer Jake Meginsky’s first feature length documentary on the avant-garde percussionist Milford Graves is an incredibly original visual and aural journey, communicating more than just a single subject matter. This is about altering our perspective on life and the way we live.

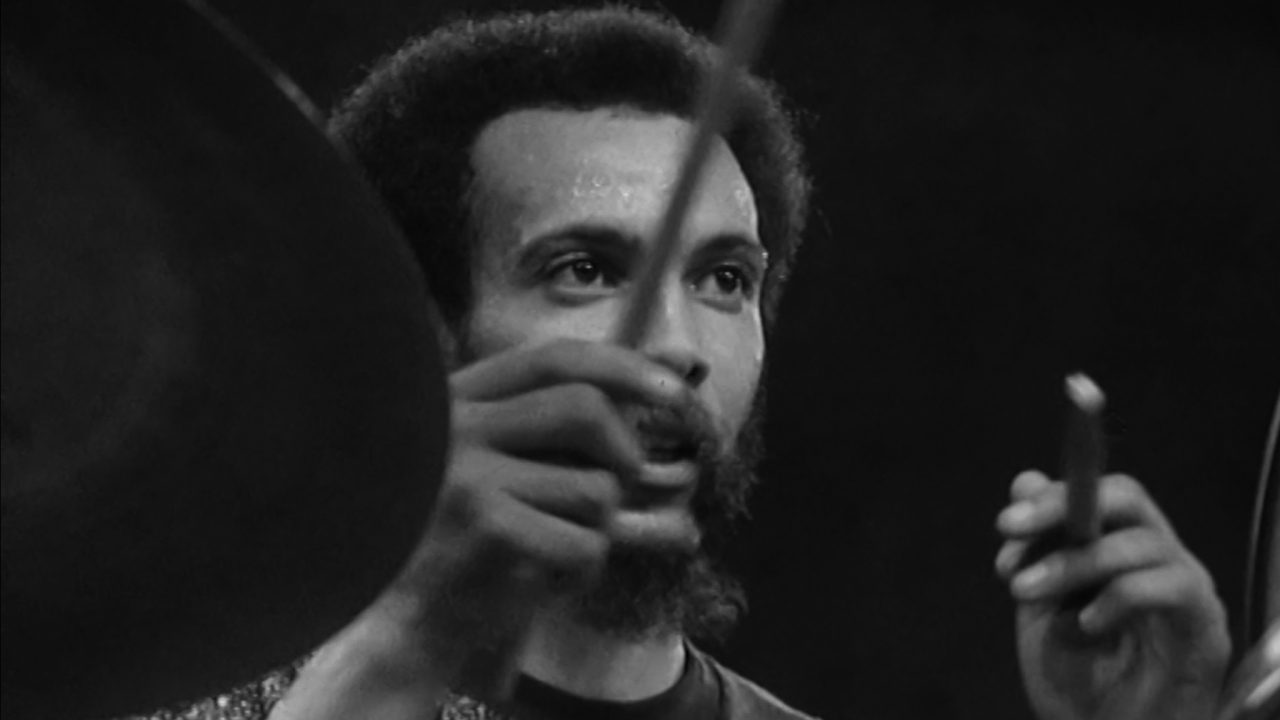

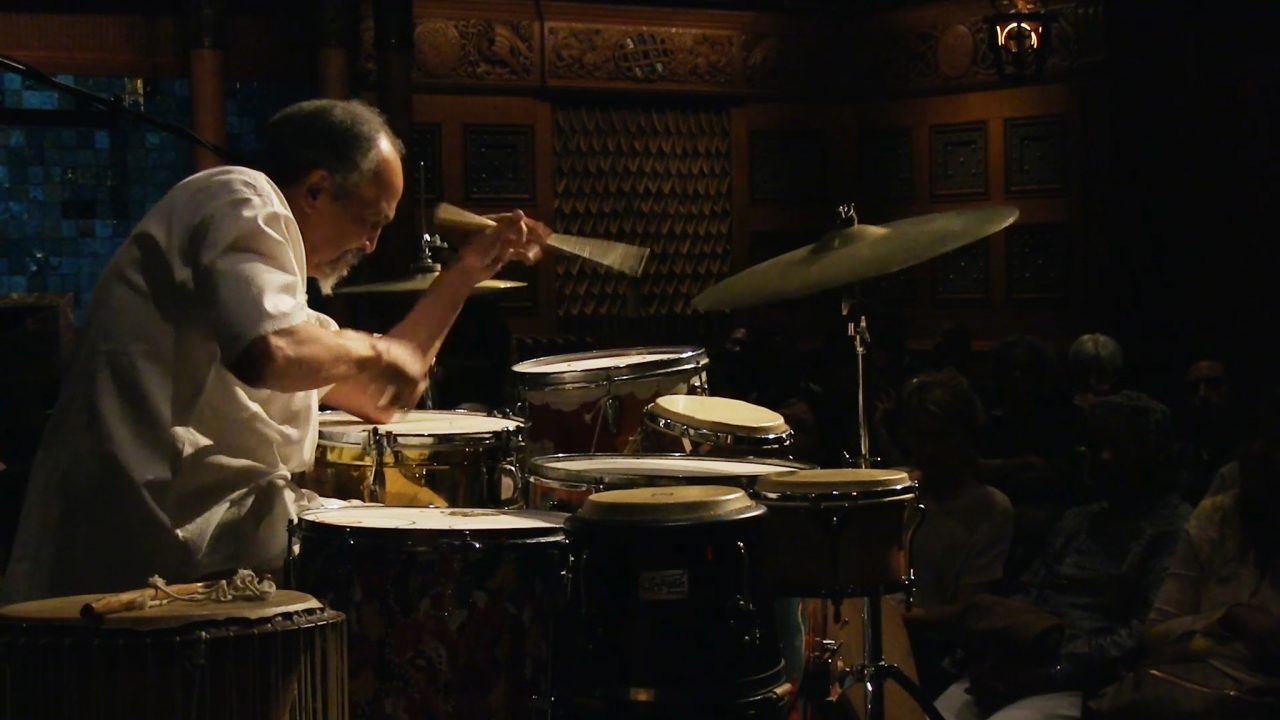

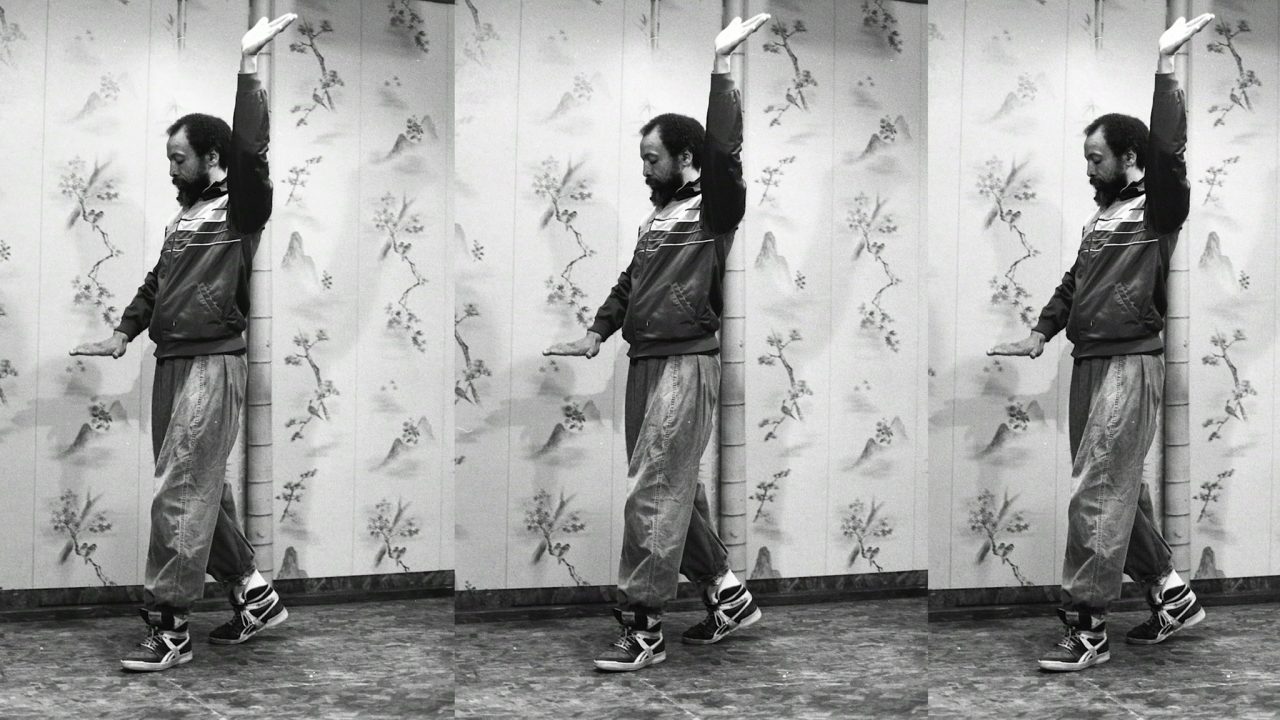

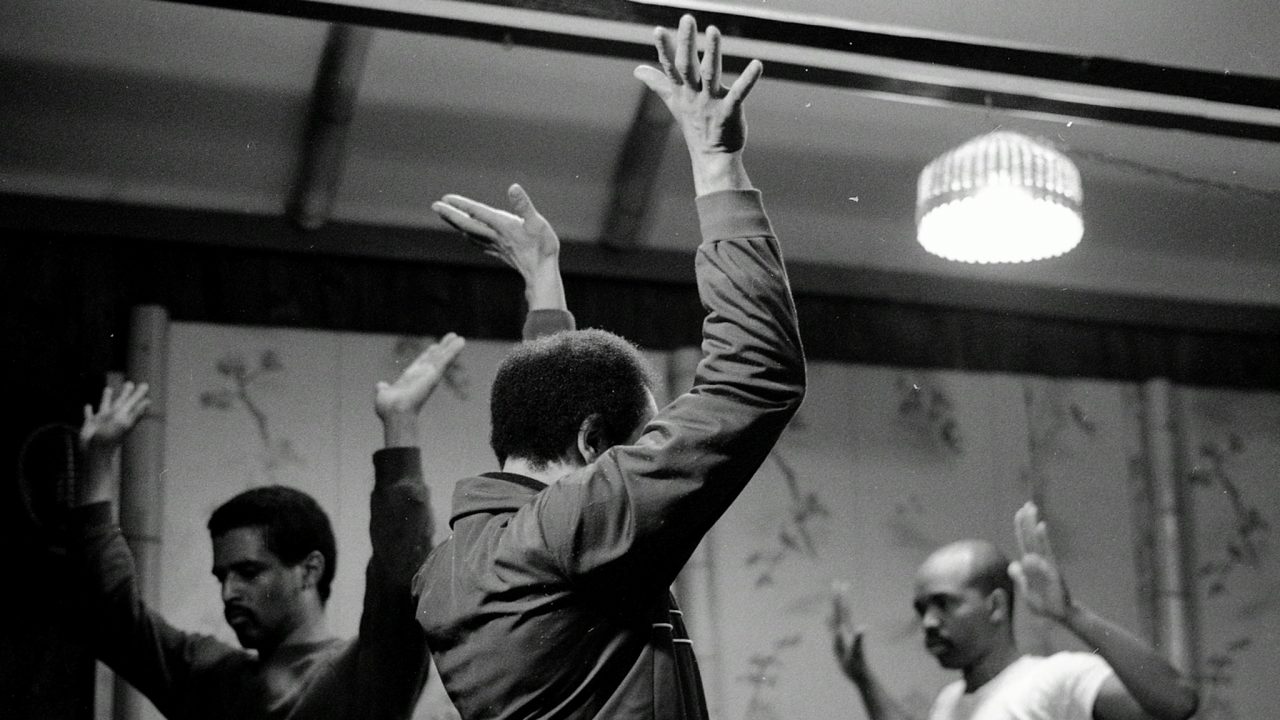

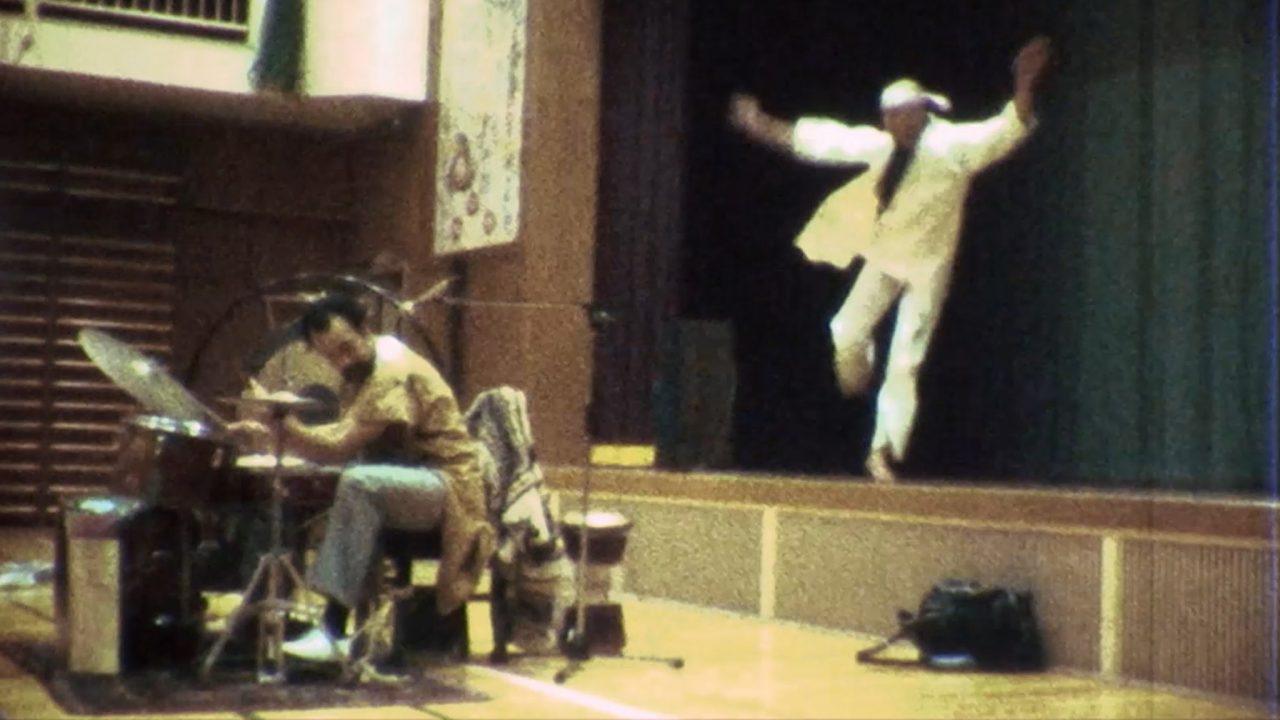

Milford Graves Full Mantis is the 93-minute documentary on the holistic artist and musician Milford Graves, 77, based in New York City, filmed in his home in South Jamaica, Queens. Using archive and current footage, Meginsky has put together a kaleidoscoptic collage of Graves’ life work. Footage of Graves in his colourful home (recognisable from blocks away), backyard (where he has his martial arts dojo) and basement (his sound laboratory is located here) is combined with archival footage of Graves early work, also performing in Japan to autistic children. Graves lives and breathes his philosophy on the power of rhythm (studying heartbeats and their altering beats) and its endless possibilities to enhance our consciousness, dedicating his own life to sharing it with others. Without dictating a spiritual or religious reasoning and outlook, Graves findings are based on physics. Combining science and the mysteries of the universe, Graves is pioneering in his research.

The originality of Meginsky’s film is striking through the way he has compiled his visual ingredients. Working with physical film footage and compiling it together literally with Graves’ philosophy on rhythm in our lives, the film is subconsciously creating another genre of film editing and story-telling. From the films beginning it is evident: Meginsky is driven by exploring and incorporating rhythm in its many forms.

An electronic producer, Meginsky also uses the medium of music in his personal work, creating under his Vapor Gourds moniker. Well-established in his own right, Vapor Gourds can be categorised as experimental music (he works with white noise and various electronic sounds), with Meginsky performing live conceptual sets in museums and galleries. His work Seven Psychotropic Sinewave Palindromes is almost self-explanatory. In addition to music, for 8 years Meginsky also worked as the Director of Education at the Amherst Cinema in Northampton Massachusetts, leading a See-Hear-Feel Film program aiming to broaden children’s minds and experiences through various international films (funded by grants, each child was able to attend on a scholarship). Another stepping stone in Meginsky’s pathway, his interests are most inevitably his motivation.

It was over 22 years ago when Meginsky first came across Graves’ work in his local record store, via a recommendation from a friend working there. This small gesture was to open a door to change the rest of Meginsky’s life. Following his work for some time, in 2002 Meginsky attended a concert by Graves, citing it as a powerful experience, “my friends were talking about feeling their heartbeat shift, there seemed to be a palpable sense that a real energy transfer had taken place. This was a vision of music as energy that I was previously unfamiliar with, music as a psycho-physical substance, with the power to change one’s body and mind.” Completely overwhelmed and taken by the musical approach, Meginsky arrived at Graves’ door in Queens, requesting to study with him. What can only be described as a like-mindedness, Graves took him on as a student (to which he still is, to this day). It’s obvious Meginsky is driven to share Graves’ way of ‘seeing’, feeling and being, through another outlet: film.

After seeing Meginsky’s film of his mentor’s work, his own mission is instantly clarified. Like Graves, he is also looking to tap into the yet unknown to enhance our consciousness. From the incredible positive response already from film critics and cinema-goers, he’s most certainly been able to successfully connect with viewers on a new level. We speak to the US-based director about his own personal pathway, his pivotal journey with Milford Graves and his overall approach as a director “responding to the situation and solving issues” – as both Meginsky and Graves jointly say.

CHAMP: Tell us about being a student of Milford’s for over 15 years. Why were you first drawn to Milford and his work, and feel like you wanted to learn from him in particular? How did you both ultimately connect and remain mentor and student for a decade and half?

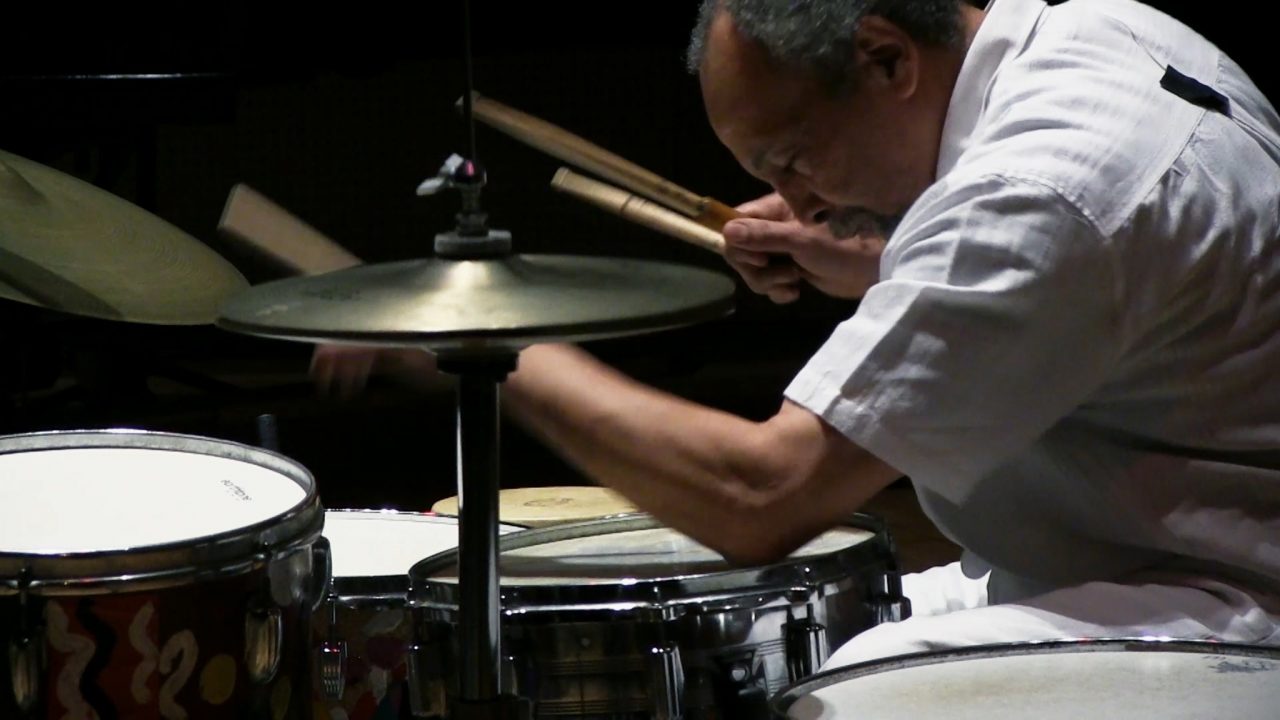

JAKE MEGINSKY: I was first introduced to Milford’s work by a friend who was working at a local record store in 1996. He knew I was a drummer and he saw me buying Coltrane, Ornette Coleman and Eric Dolphy records so I could practice along with Elvin Jones, Ed Blackwell and Tony Williams. He turned me on to the Milford Graves Percussion Ensemble on ESP Disk and I was blown away. I played along to the record and I was compelled to improvise with Milford and Sunny Morgan, rather than to copy, as I had been doing previously. There seemed to be an inherent expansiveness in the music, with pockets of space and asymmetrical rhythmic statements that I found fascinating. A couple years later, in 2002, I attended his solo concert at the Fine Arts Center at the University of Massachusetts. The performance proved to be even more cataclysmic, creatively, than listening to the records. The music itself was phenomenal. But what struck me most was the physical effect the performance had on the crowd. When the lights came on, everyone’s faces were flushed, my friends were talking about feeling their heartbeat shift, there seemed to be a palpable sense that a real energy transfer had taken place. This was a vision of music as energy that I was previously unfamiliar with, music as a psycho-physical substance, with the power to change one’s body and mind. I was so taken by this concert, I eventually quit my job, and presented myself at Graves’ door. I waited for almost an hour. When he arrived, I asked him if he would take me on as a student. It was an impulsive decision — I was nervous I would be rejected on the spot, and I didn’t have another plan. He looked me up and down and said, “Come on in, we will see what the story is…”. Without another word, he directed me toward the purple drum kit in his studio. I grabbed a pair of sticks, took a seat and noticed the timbale in place of the snare drum. He sat down on an old, and slightly out of tune, upright piano, and we proceeded to play together, improvising for almost an hour. In the following months I started working as his assistant at Bennington College, teaching intro percussion courses and assisting in the laboratory. I stayed at Bennington from 2004 to 2010 when he retired, but I continued to work with him at his house in South Jamaica, Queens where I still study with him and help out with various projects as they emerge.

How would you personally describe Graves as a person, now, after knowing him for so long?

Graves is the most generous person I’ve ever met. Clearly a creative genius and a dynamic, hard-working polymath – he is compelled to share the deepest secrets of his multi-layered creative process. Milford holds both the scientific process and the mysteries of spiritual experience with the same grip – it’s like his double stick technique. He cares deeply about all of his students, and his teaching has a transformative quality that changes the way one thinks on a very deep level. Milford does not turn out copies of himself but rather injects a sense of radical individuality in those he connects with. You can see it in his martial art, Yara. All the Yara students have their own style, but they all have a Yara flow, marked by a deep sense of embodiment and originality. Whenever he gets an opportunity, he extends it to all those around him, in order to lift up everyone involved. The path of his students varies widely — they are neuroscientists, biologists, painters, lawyers, writers, business owners and musicians. However, they all share a potent access to the power of personal creativity. Very few teachers are focused on developing in their students an original voice, it is the big mystery, yet Graves focuses on this – as he would say, “I’m trying to see how you vibrate inside”. He is a family man, who has raised five children and has been married for over 60 years. The stability of his home life seems to be the foundation that provides him a launch pad to travel the cosmos of creativity, sound and science. He is my great mentor, and he is also a collaborator and a close friend.

This is your first feature film. Can you tell us what drew you to create it?

This film is a labor of love that gained momentum over time. It is a DIY project — I directed and produced it with no budget, but I had the help of many friends along the way including my great collaborator, Neil Young, who is also a drummer. The film has taken different shapes along different points in its life cycle. After meeting the Professor, I had an immediate sense that I was in the presence of a truly spectacular mind and was compelled out of a sense of duty to give back by helping in whatever way I could. At first I was recording his lessons so I could contemplate and reflect on what he was saying. This evolved into smaller projects, sometimes to provide an audio/visual component for Milford’s lectures or performances. Other times I was thinking of the growing collection of material in terms of adding to the living history of an important archive that chronicled the work of an amazing artist. Eventually Milford started giving me archival footage, and the experience of watching the material was so cinematic, that I could start to see shadows of structure for the feature film and I could begin to hear its voice. In many ways it feels like the project chose me. I actually don’t remember deciding to make it – more just “responding to the situation and solving issues” as Milford would say.

How long did it take to complete the film, from initial conversations with Graves to final edit? Additionally, what were some of the unexpected challenges you faced?

From the first time I recorded Graves with a mini-disc recorder, to the premiere of the film it was around 15 years. There were initial challenges in finding the film inside the hundreds of hours of material on the hard drive, learning how to ask it what it wanted to become, and learning how to respond to it when it asked something of me. There were technical challenges, especially towards the end. Since it was my first film, I had to learn how to manage the process once it was out of my computer – both into post-production, and then on to managing the rollout of the film and trying to ensure it was presented in a dignified way. The whole thing was created on a very steep learning curve.

You’ve cited filmmaker Stan Brakhage as a previous influence to your work, can you tell us more about him and other influences to your work perhaps consciously and subconsciously?

I love Brakhage’s focus on sensorial perception. He had the idea that cinema could actually alter one’s perceptual experience and “give the viewer a new set of eyes”. I feel like cinema, which is the artform that activates our sight, our ears and our sense of touch (both sonic touch through the low end, but also the body through the installation aspect of cinema – the comfortable seats, the proximity to other patrons etc…), is uniquely able to impact the way we experience our senses, the “five part harmony”.

Actually, the scene in Full Mantis where Milford coins that particular phrase in reference to the senses, while working in his garden, is a direct visual reference to Stan Brakhage’s work. I feel like the emotional content of Brakhage’s more abstract work points to a physical embodied morphology underneath our consciously felt experience of the world. Music works like this too. A single Bach cello suite can make you feel joy, sadness, longing, or exuberance because it is accessing the deep patterns in our body/mind, and in these complex cellular and sub-atomic patterns the difference between pain and pleasure is very small. I think of this morphology as deep narrative – they are the stories underneath the stories.

I’m also influenced by filmmakers like Les Blank, who made films about the ephemeral and sensorial nature of music and food – where the visual aspect of the film itself would dance with and take the shape of the sonic or taste sensations he is documenting.

Tell us about growing up in Northampton, Massachusetts, and your pathway from there.

I’m from Springfield, Mass, an industrial city about 25 minutes south of Northampton. When I was about 16, my friends and I began to drive up to Northampton to see jazz concerts and films at the arthouse – I was quickly exposed to the deep stuff, all under the tutelage of cognoscenti who populated the town in the 90’s. There was a great video rental spot up there, and the folks who worked there turned me on to a lot of things. If I took out Fellini, when I returned, they would have some Pasolini and Antonioni put aside for me. There was a whole Les Blank section there too.

I always wanted to move to Northampton and eventually I did. There were also amazing free-jazz and experimental music concerts poppin’ off all the time: Fire in the Valley, Magic Triangle, The Flywheel, and other series and venues were routinely presenting free-jazz legends like Ed Blackwell, Alan Silva, William Parker, Sabir Mateen, and Daniel Carter. On a given weekend you could catch Thurston Moore improvise with Adris Hoya (Hairy Pussy) in a tiny office space, then see Byron Coley read poems, and the following day catch Marshall Allen (Sun Ra) playing at a Unitarian church or Pauline Oliveros pumping an accordion drone in a library atrium. Neil Young was also presenting experimental film and video there in his Bright Rectangle series, which was formative for me. It’s a collection of small towns, but the vibe is big and the ethos of experimentation is part of the fabric of the community. So much creative activity, and unlike bigger cities, there isn’t really the spectre of “success” looming over it all. Instead there is space for people to explore and make anything they want without an overly forceful feeling of borders between the scenes.

There also is a sense that you should take the time to figure out what you want to make. In many ways the film grew out of the ecosystem of Western Mass and is indebted to the community as a whole. Everyone I am close with lent a hand at different points in the history of the film.

Unlike your music made as Vapor Gourds, your ‘Seven Psychotropic Sinewave Palindromes’ album released under your own name was made with only four tools – sine waves, square waves, white noise and an 808 machine. Your work aims to engage listeners with unheard sonic properties of everyday structures and settings, and aim to explore “the perception-altering qualities of music”, as performed in your Sound Installations. What do these man-made devices have in particular that natural tools or instruments cannot?

Seven Psychotropic Sinewave Palindromes was made with the core elements of electronic music. While it’s true that pure waveforms are not found in nature, once they hit the speaker and the speaker cone vibrates air and the air hits our body and our eardrum, they become physical and they interact with the natural world. When using pure electronics I think of the speaker cone as an instrument to be played by the waveforms. The magnets of the driver in a speaker go up and down according to positive and negative charges, so using pure waves is way to access that in a direct and perceivable way.

I became accustomed to the restricted sonic palette in Milford’s lab, because sinewaves and squarewaves are the sounds he uses to sonify the heart recordings in the LabView software he uses (including my own heartbeat). These sounds feel organic and human to me as I relate them to the sound of the circulatory system. While making the record I was thinking about patterns, geometry, and how the experience of, and exposure to patterns, over time, can alter the way time and space are perceived. Restricting the palette and timbre helped me focus on complexity in compositional structure and the psychological effect of the music. I find that when I make music with electronics, it really informs the way I think about the drums, and vice versa.

Inventively putting together these digital elements to create new sound experiences, do you do this intuitively? For instance when you create your Sound Installations, do you follow a structure for the work or do the rhythms created take you on a journey?

I usually start working with a loose idea, get to work and then wait for the thing to start telling me what it wants to be – once it starts speaking it usually either changes the nature of the original idea or absorbs it into something larger and more textured. So the process is intuitive, but it has to do with paying attention to the materials at hand. Sometimes it happens really fast, and other times it can take a while.

I love doing site-specific installations because I can show up with a bunch of materials and the space itself starts to point towards a new approach. I like to start one way and leave different.

Would you agree that rhythm, in its many forms, is the thread making up the tapestry of the universe? And do you approach your work thought-process practically or spiritually?

Vibration, cycles, wavelets, and pulsations seem to be the substrate of our experience of reality. I think musicians interact with this substrate in a direct way that is both practical and spiritual. My friend Elaine Kahn just shared a poem with me by Kamau Brathwaite:

“God is dumb

until the drum

speaks”

Sometimes an acute attention to form can lead to a divine and spiritual place. Other times a spiritual experience, or the radical/spiritual form of presence that is required for improvisation, can unveil an undiscovered sense of form. In my work I’m looking to change. It doesn’t feel done if I’ve started one way and end the same way. The transformational aspect of art-making is what interests me, the way a creative engagement with your sensory experience can lead you towards previously uncharted ways of thinking and being.

You’ve previously worked as the Director of Education at Amherst Cinema, leading your See-Hear-Feel Film program, which aims to broaden children’s minds and experiences through various international films. Funded by grants, each child is able to attend on a scholarship. Can you tell us more about this, and what you learnt here at the cinema about the power of film?

For 8 years, every weekday, I watched film and discussed film with third-graders in a program that helped kids who were struggling to write and read find a platform to discuss ideas and explore their creativity and their intelligence. I learned how to watch and listen like them. This experience was invaluable, and without it, Full Mantis would have come out differently – if at all. They taught me how to approach a film in a visceral, physical way and to not project narratives onto the sensory experience. They see things we don’t see, and they hear things we don’t hear. An 8 year old is still connected to the infant inside, yet they can speak about experience in a very sophisticated way. They don’t yet have the social intelligence that forces them to double think everything they express.

I believe we should have think-tanks with 8-9 year olds to advise on global problem solving and policy – they don’t really do metaphor, they get right to the core. There was also the aspect of repeated viewings of the same clips over and over. This gave me a lot of information regarding the multiple layers operating simultaneously inside a filmic experience, and I found it extremely helpful when I got to thinking about the total structure of Full Mantis. There are some edits in Full Mantis that are directly related to films I used in the program –films I watched 100’s of times while sitting in a theater surrounded by kids.

Finally, what’s next for you? You’re currently touring Milford Graves Full Mantis, reaching the UK later this month. Do you have a distribution deal yet, and are you working on your next project?

I’m still on the road with the film quite a bit. I received a lot of distribution offers but I’ve decided to do the theatrical release myself, with the help of some close friends. It is really important that the film plays in cinemas, and many distro deals favour a quick move to a digital release because a theatrical release is tedious and doesn’t really make anyone any money. Milford Graves Full Mantis is meant to be seen in a room with a group of people, so I’m spending a lot of time fighting for that and shepherding the film through the maze. Milford was hand-painting his records since 1964 on his own Self Reliance Projects record label (SRP), so retaining control over how the release works has helped the film stay in tune with Graves’ vibe, which for me has been an essential part of the whole process.

In the fall of 2018, Milford has a big sculpture show at the Queens Museum and I’m helping prepare materials and projections for that. I have a few film projects that I’d like to start work on when I’m home for a bit. I’m also currently working on a new solo record for NNA.

∆∆

Interview Monique Kawecki | London Editor-In-Chief

Photography as credited

For more: www.fullmantis.com