FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT HOUSE AND STUDIO

American Architect Frank Lloyd Wright’s First Home and Studio Is Nothing Short Of A Masterpiece

Renowned American architect Frank Lloyd Wright’s most ground-breaking design was infact for his own Home and Studio in Oak Park, Illinois, built at the age of 22. First completing the house and then adding to it a studio next door, this was to be an on-going project for the next 20 years of Wright’s professional career. Both the Home and Studio showcase and solidify why the American Institute of Architects would pronounced Wright as the “greatest American architect of all time”.

Born in 1867, two years after the Civil War ended, Frank Lloyd Wright grew up in a small town in Wisconsin, Illinois. He attended the University of Wisconsin and studied engineering, and after college became chief assistant to architect Louis Sullivan. Whilst working with him in 1889, Wright bought land in Oak Park, and through a generous loan of $5,000 given to him by his mentor Sullivan, this was to be Wright’s first realised architectural project, and the first home for Wright and his wife Catherine later in 1895.

His years of work under Sullivan helped shape Wright’s own vision and approach to organic architecture, a term created by Wright to describe the overall philosophy of his work.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s House

Wright built the house in the Shingle style of design, but it was here he developed his renowned Prairie style of architecture. The Shingle style was influenced by English architecture combined with elements of Colonial American architecture, remaining fluid in its skeletal structure. At this time in the 19th century there were a lot of changes. It’s important to note that this was sixteen years after the Great Fire in Chicago, and the city was open to new processes and possibilities within construction and engineering. At the time, Oak Park was a semi-rural village and had only been settled as recently as 1830 by pioneering East Coast families. Titled Saint’s Rest, there was an abundance of churches in Oak Park, and the solitude of the area provided incentive to wealthy families to find solitude here and build their elaborate homes, as did Wright.

Wright’s Home and Studio were a place where he experimented with space, form and light. He had complete artistic control. Materials, furnishings and decorative arts intertwined their way into his output, and are found through the Home and Studio in obvious or minute detailing. Always interested in the ‘journey of discovery’, at both the Home and the Studio the front door is hidden, with Wright’s interest to evoke curiosity and allow that to lead the guest on their way.

From its conception, Wright would continue to adjust and alter the living spaces in the house according to his needs, and later the needs of his family. His love to entertain was evident with the architect soon modifying the kitchen that was initially built into a dining room: he loved to have artists, writers, clients and friends over for supper. Wright’s furniture designs were used and presented harmoniously with the architecture; the design of the table and chairs remain part of Wright’s organic architecture philosophy, with their fluidity working in tandem with the home. Wright’s Egyptian pendant lights were the same, and his influences were experienced also by guests, with design detailing signifying his travels. For instance, Japanese ceramics and small Greek sculpture replicas were displayed on window ledges, with Japanese rice paper used to dim the lights above the main dinner table. Later, Wright would be one of the first to install electricity into his house.

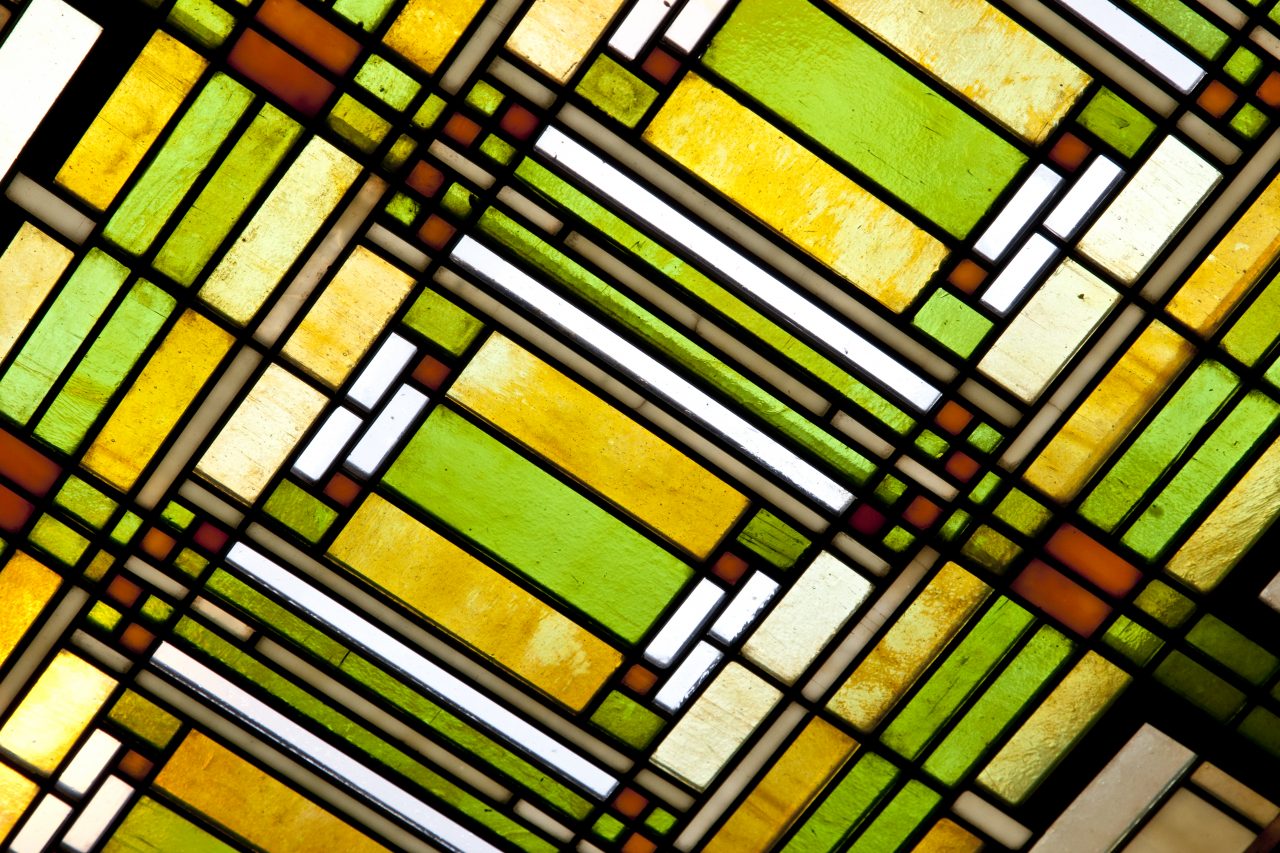

Upon entry into the house it is evident to see key signature details which could only be of Wright’s vision. A palette of green, gold and white is strikingly evident at first arrival, as are the rectangular and semi-centre windows presented throughout the house. Wright thought in geometric concepts and this way of thinking was reoccurring throughout his life’s work. Wright loved Greek sculpture, and a replica of the Venus de Milo is found in the entranceway, greeting guests upon arrival. At that time period, Wright and his wife felt it was important to have beautiful things in the hallway. Also in the entranceway, above the light green moss walls is a cast reproduction of the ‘Battle of the Gods’ (a recently excavated alter piece which Wright saw in a catalogue) that was used as a theatrical trimming.

At this time, the American Arts and Crafts movement was also gaining momentum, as its principles had been adapted by the English Arts and Crafts movement which had made its way to the US. Adopted by Wright, he embraced the strong philosophy of craftsmanship, simplicity and integrity in art, architecture and design within his own architecture.

The central fireplace design with seating right next to it can also be found in most of Wrights’ other designs, whereby Wright also aimed to accentuate the importance of time spent here reading, thinking and learning. There was always a play with the flow of space and the central fireplace is a prime example: although it was built as a small room within itself, its walls were open, so one could see through to the rooms to the living spaces in front, and to the left and right. Wright even placed a mirror at the top of the Roman brick fireplace area to give the illusion of more space. His ‘room within a room’ was a continuous trait.

The Children’s Playroom is another key example of Wright’s organic architecture. This room was designed to be multi-purpose, allowing the children to do as they pleased in the large open space. It could hold performances, small theatre shows, and Wright even taught kindergarten in the children’s Playroom. Infact, a Steinway piano sits in the corner beneath the Playroom’s ‘theatre’ seating and the cabinet of Wright’s influences (such as a set of Fröbel blocks) and was also used to share Wright’s love of music. This Steinway is indeed Wright’s own, it is the original, intact wholly apart from its legs which Wright removed to fit into the space. Lotus lamps were also added to the Playroom after the Wrights returned from Japan, and their design compliments the strikingly colourful stained glass windows. The mural on the back wall, painted by Orlando Giannini, is a centrepiece of the room, displaying a fisherman, genie and a Mosque in the background. A beautiful reference, Wright’s children liked stories such as Thousand and One Nights.

The bathroom currently displayed in the Wright House is the original from 1889. At the time, it was unusual for a middle class home to have such a bathroom design, yet Wright designed it for functionality and practicality.

The house continued to change and evolve, and in 1911 Wright even installed a two-car garage next to the house.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Studio and the Prairie Style

In 1898 he built the studio next door to the house. His Home and Studio were where he tested and applied his thoughts on organic architecture – which he originally learnt from Sullivan – to later be known as the Prairie style of design. The Prairie style used strong geometry, open and assymetrical floor plans, large central chimneys, brick exteriors, interior wood banding and an exploration of motifs (a nod to the Arts and Crafts movement). With an emphasis on nature, craftsmanship and simplicity, the Prairie style redefined home living in America, striving for an organic architecture in designs for homes, studios and commercial buildings.

Birthing the Prairie School, championing by up-and-coming talented architects sharing the same vision as Wright, these individuals would work together to redefine modern architecture. They ultimately reassessed architecture as it was, and created a new movement seeking democracy in design, now a key moment in America’s history (by 1915 however, tastes changed and the movement faded).

At Wright’s studio, six architects would work at a time, all perched at the desks and benches also designed by him. Each had their own desk and filing cabinet to store works, and these architects supported Wright’s vision, contributing in their own unique ways. Later Wright would refer to them as ‘The New School of the Middle West’, and the architects included Vernon Watson, William Gray Purcell and Myron Hunt amongst others. In particular, architects Marion Mahony (who was the second woman to graduate from MIT in architecture, and first women to be certified as an architect in the state of Illinois) and Walter Burley Griffin championed the Prairie style and the new way for modern American living. They were friends to the Wright’s and key original members of the Prairie School, later going on to work in India and Australia through their own practise.

Glass sculptors worked upstairs in the double-floored main room, and they would design stunning glass works such as the lighting in the studio itself. Dangling by octagonal chain harnesses, the lighting structures in the room were also used to stabilise the ceiling. With the wooden infrastructure of the ceiling also an octagonal shape, this clever chain solution was created to prevent the ceiling naturally leaning out, with the chain bringing the ceiling inwards, and thus balancing it out and keeping it equalised. A large safe was also installed in the studio, and would keep Wright’s rare Japanese prints safe.

The lending library in the studio was also built and designs with various octagonal forms (the table, table legs, windows).

Influences

Wright was interested in different cultures, music, nature and geometry, in addition to the work of his mentor, Louis Sullivan. These influences are evident throughout Wright’s built works, and through the pathway of his career.

Intrigued by Japan, the country became a recurring destination for him and his wife Catherine. The first passports issued to Wright and his then wife are found displayed on the second floor of the house when the couple went in 1905 (Wright would also later go on to live in Japan whilst working on a project).

Wright would collect rare Japanese prints on his travels, and build specific displays for them in the house. When things got tough he would sell them, and later buy more when he was in a better financial position. Wright even later went on to exhibit his collection of Japanese prints at the Institute of Art in Chicago.

Beethoven was also a significant influence, with Wright identifying an architectural element to music which he would later communicate through his work as a music professor at the end of his life.

The geometry of Fröbel blocks influenced Wright continuously, with the blocks teaching the different shapes also found in nature. Wright’s mother found a set of blocks at the 1876 Worlds Fair, and he kept them in the Playroom for the children to learn from.

Oak Park and Chicago

Wright sold his Oak Park build in 1925, and by 1974 it was in a terrible condition. The Frank Lloyd Wright Trust took 13 years to recreate the property to what it once was in 1909 (the last year that Wright lived in the home). After on-going intense restoration works were complete, the House and Studio opened to the public. The landscape surrounding the house was also restored to present accurately the original plants inhabiting the area in 1909. Landscape architect Carol Yetken and her firm, CYLA, took on the role and have worked with the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust on a long-term basis, overseeing seasonal and yearly changes. One pillar of the plant kingdom is the Gingko Biloba tree situated in the middle between Wright’s House, Studio and home he built for his parents next door. Only 4 inches in diameter when he first planted the tree, now over a century later the tree looms above them with all.

Wright’s ideas and style would later also be built in his work for his clients’ Oak Park surrounding homes in the historic neighbourhood. It is indeed an educational experience, with 21 other Wright-designed structures also in the area, with house walks and guided bike tours available via the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust website. In Chicago, tours are available for the Frederick C. Robie House in Hyde Park, The Rookery Light Court in Downtown Chicago and the Emil Bach House in Rogers Park. The Emil Bach House, built in 1915 for Emil Bach (president of Chicago’s Bach Brick Co), is the only Frank Lloyd Wright-designed overnight stay venue in Chicago. The home has been meticulously restored to Wright’s original plans, and it presents Wright’s earliest stylistic design traits in addition to providing hints into his way of thinking for future works. The newly-restored Unity Temple in Oak Park is Wright’s only surviving public building from his Prairie period. Built originally in 1905-08, it was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1970, and in 2017 major restorations that had been done were complete. The temple was constructed of exposed, poured-in-place reinforced concrete, made unconventionally through the use of materials and processes reserved for factories and warehouses at the time.

Wright’s comments on his work clarify his approach, “Unity Temple makes an entirely new architecture – and is the first expression of it. That is my contribution to modern architecture”.

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT HOME AND STUDIO

951 Chicago Avenue, Oak Park, Illinois, USA

Museum Shop Open Daily 9 – 5pm

Text: Editor-in-Chief Monique Kawecki | Thank you to the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust team