ANTHONY McCALL: SOLID LIGHT WORKS

The Hepworth Presents The New York-based British Artist's First Major Survey In The UK In Over A Decade

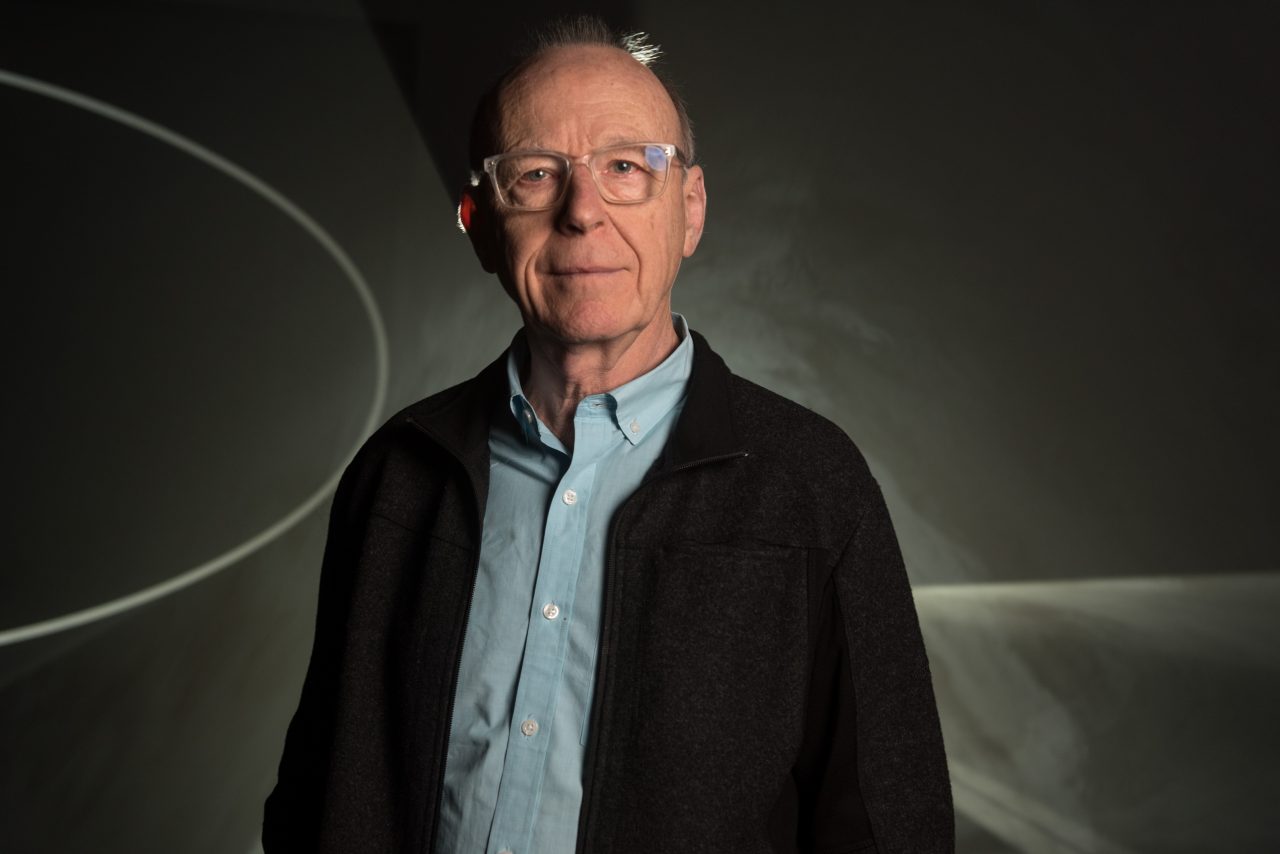

Exhibiting until the 3rd of June, The Hepworth Wakefield presents a major survey of British artist Anthony McCall’s work, titled Solid Light Works. The New York-based artist returns for the mini-retrospective of his works, the first exhibition in the UK in over a decade.

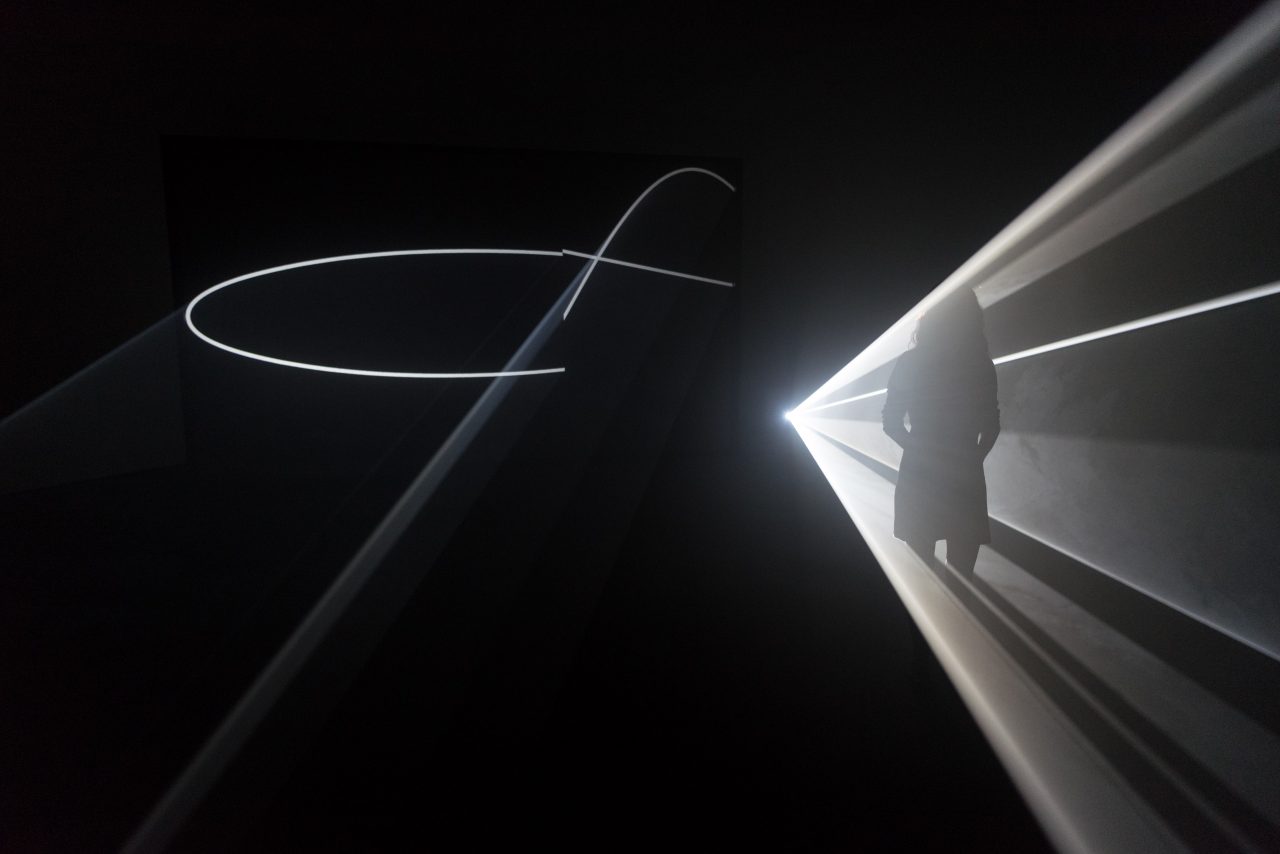

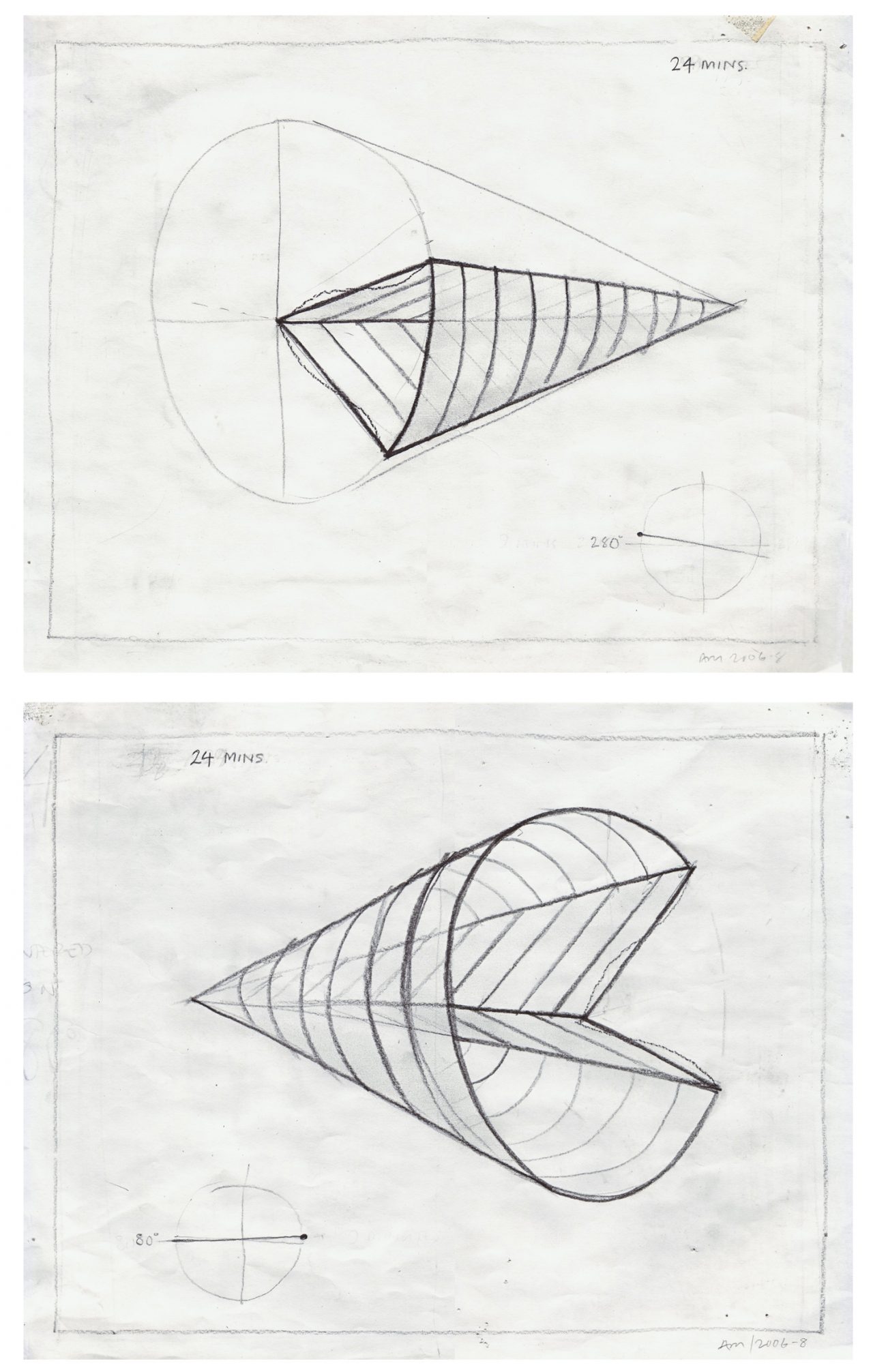

A pioneer in the truest sense, McCall began his light works in the 1970s, innovatively working with light and exploring new possibilities by sculpting it, leading the way with his refined approach. Working with minimal tools, renowned works such as Line Describing a Cone (1973) showcase McCall’s then-original approach to working with light, speed and temporal structure.

Described as ‘occupying a space between cinema, sculpture, and drawing’, McCall’s beams of light are made only with projected light and smoke haze, using speed and time as defining factors (McCall’s interest in the foundations of film can be found here). The immersive works invite visitors to interact with them, encouraging curiosity, evoking a wariness often followed by pleasant surprise. For the Hepworth exhibition, three solid light works are installed, with two being double-projections. Engaging and consuming, these temporary structures are all based upon McCall’s vocabulary of using straight line, circle and wave. This minimalism is perhaps what enables McCall’s work to be understood and enjoyed by many. Less is more. But as all wonderfully-simple works find effectivity in engagement, their creation is often strategically engineered. The solid light work Doubling Back made in 2003, but re-created here in The Hepworth, combines horizontal and vertical waves crossing one-another. The mathematical precision to have these waves cross each other in harmony must have been more than technically challenging. A far cry from their original elements, McCall’s current works require a blackout environment and specific room temperature for the haze to maintain its animation.

At the heart of the exhibition are sketches, photographs and films presenting McCall’s approach and thought process, with his foundations found primarily through drawing. This can be traced back to when his art practise began in 1964, when the young creative attended the Ravensbourne College of Art and Design studying graphic design and photography. Later, a key figure of the avant-garde collective London Film-makers Co-operative in the 1970’s, McCall’s earliest works were powerful to experience. Landscape for Fire, an outdoor performance created in 1972, used only fire and McCall’s technical precision as tools to convey his message. Moving to New York in 1973 with American artist Carolee Schneemann, this was the city that would forever capture McCall’s heart. But his career path was not always linear. McCall found that his solid light works relied on cigarette smoke and warehouse dust to be realised. Only ever presented in DIY warehouse spaces or Soho lofts, this was a new realisation for McCall, finding his works were heavily reliant on these factors. They could not effectively be re-created in a pristine white-walled gallery environment.

So began McCall’s 20-year hiatus from the art world.

Setting up a graphic design studio in the meantime, McCall’s career path redirected to designing art books. It was in the late 90’s when the film industry invented the smoke machine, and the door re-opened for McCall. It’s liberating for others to know that after such a hiatus, it is possible for an artist to re-enter the art world where they had pressed ‘pause’. Going on to exhibit at art institutions such as The Whitney Museum of Art in New York in 2001, the Kunsthaus Zurich in 2006, the Serpentine Gallery in 2007 and MoMA in 2010, McCall’s career progressed at a positively steady pace.

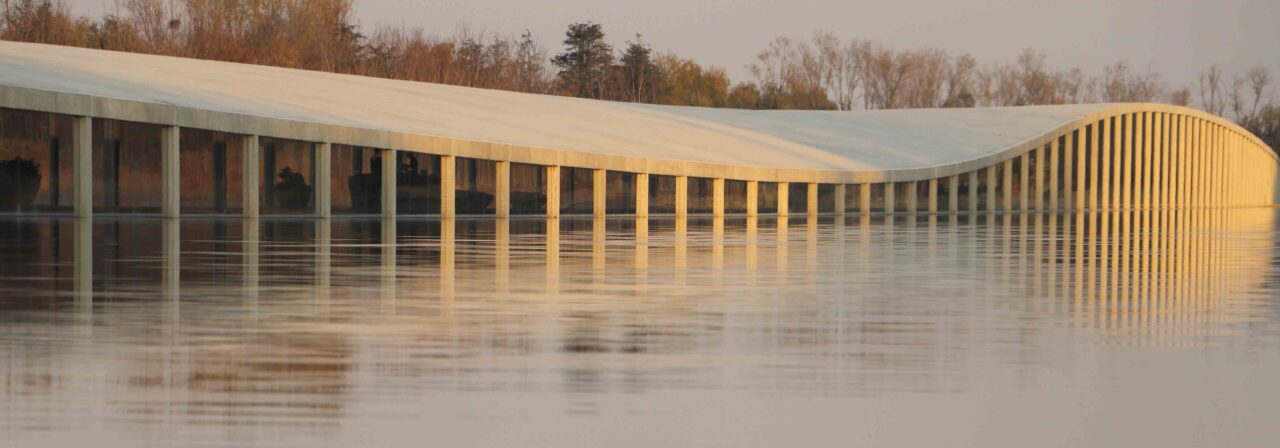

Now, presented at The Hepworth, McCall’s work is shown almost in it’s entirety. His solid light works are presented to a new audience, a new generation, exhibited in a David Chipperfield-designed art gallery. Finding a “sympathetic hum” from the building, McCall explains that Chipperfield’s architecture creates a space extremely easy to work with, explaining “the angles are not quite 90 degrees”, finding them not rigid, but open form, therefore creating new possibilities in the space. Also describing the architecture as ‘sympathetic’, McCall’s 10-foot works are at ease in the space.

For the opening of the Solid Light Works exhibition, the Hepworth director Simon Wallis invited the public to the evening opening reception, something The Hepworth do for every exhibition opening (anywhere else PV’s are almost always reserved for press, collectors and art industry invitees only). This gesture highlights the openness of The Hepworth, creating a community-driven space in the heart of industrial Wakefield, Yorkshire. On the eve of the opening, we spoke to McCall about his preparations for the exhibition via his studio in New York, and his overall approach to his art practise. We sought to explore more about what his underlying motivation and inspiration for his work was. What we found was an extremely modest artist, as approachable as his art is.

Elements of the space where your work is exhibited in is very pivotal – such as air currents, dust. What were the technical challenges to installing this work here at the Hepworth Wakefield?

My work is not site specific, so the work preceded this exhibition – it was already made. It exists in quite tight parameters, and they’re scaled to the human body, with my project beams usually 10 metres long and if they are vertical, they are ten metres tall. It’s really a question of finding an institution that has the right size spaces. These [spaces here at The Hepworth] are the perfect size for my work actually.

So again, my work is not site-specific, but it is site-sensitive. Once I’ve looked at a space and I’ve studied the plans, I do carefully think about how the work should be configured within it. I also do what I do for any important show, is that I built a scale model in the studio, so we are able to to look at it, and we put the work in it. I visited the spaces, so I knew them to some degree, but I spent months using the models. It was very interesting then arriving here to install, having thought I knew the spaces through the model.

A bit of problem-solving?

Many of the problems have been sorted before I come, but for instance I realised I needed an extra wall for the 1970s works, so I built that. I actually played around with the model to see where they would go. The marvellous thing about these rooms, they are sort of square, in a soft kind-of-way, they’re not always 90 degrees. They are very sympathetic and accommodating, they seem to welcome you. It’s very interesting, it has no rigidity this space. It has plenty of structure. It has these wonderful radiating ceilings with skylights at the top.

Designing in a specific space, to a visitor the space does seem rigid.

An exhibition has its own narrative demands, it wants to unfold itself within the space its given. There’s reciprocity, and that reciprocity is what you play with in the design of the exhibition.

Through your experience of designing art books, layout and function, do you think that led to aid your design and layout for this exhibition to clearly communicate your work?

I like designing books, it comes easy for me, I like it. I don’t think it was the influence from graphic design, rather my sensibility chose graphic design to study. I already have that space for space and precision. Graphic design has some of those qualities. It overlaps with architecture too. Some people think in three-dimensional terms, I find I do. I use drawings and models to help me through it. I don’t think the drawn work would be a surprise to the architect, I’m sure David Chipperfield does some of the same things.

The same language… Your works could be described as architectural forms.

It has an architectural face to it, it does. It’s not true architecture because it has no plumbing and people don’t live in it, but particularly the vertical, but also the horizontal works, have architectural references inevitably. After all, they are spaces that you inhabit. There is an overlap, but they have very different aims.

With your works holding a connection to cinema and sculpture, were there any major influences in your youth which made a strong impression on your work now? Previously you have mentioned Kurosawa’s film as a reference to the ‘wipe’ movement in your works.

I was looking for an example of the ‘wipe’ online, to show people where it came from cinematically – and that was the one I found! It wasn’t anything that gave me the idea though…

Through your love of using cinematic elements, do you know where that may have started?

No, I don’t…! In regard to early influences, the things I remember thinking ‘this is fantastic!’, well, there are two things: one was the Rauschenberg show at the Whitechapel Gallery curated by Brian Robinson in about 1964, when I was still in school. He had all the assemblage places, those which aren’t that famous, the ones with the goat and the bed on the wall. He also had the Dante’s Inferno drawings. I was completely astonished by that show. I read a lot about Rauschenberg after that show, and found him a very interesting figure.

Another work was John Cage’s installation called HPSCHD. He had seven or eight harpsichord’s in a circle, and each harpsichord was a player, and they played different pieces of music. Walking around that space as a visitor, understanding your role was to mix the work, you made it up, was a revolutionary experience. I’m sure it tapped into my solid light forms.

We were previously speaking about the visionary Richard Demarco Gallery, who exhibited Joseph Beuys, and also your early work.

He was a marvellous, adventurous gallerist. Still with us, I think. He was very hospitable. I needed to do a piece, and he said ‘well do it here!’. It looked like we were burning the building down, just with the smoke generator. The fire brigade came, and he immediately called a press conference and said, ‘if his artist wanted to burn down the gallery that would be fine!’

Loyal to the works!

…Most fire sensors can’t tell the difference between hot and cold smoke. We use cold mist…

Continuing on the queries to your influences, you mentioned Warhol’s early film work had an impression on you?

What I like about Warhol’s work, particularly ‘Empire’, is that it used time as something quite literal. He shot the Empire State Building over eight hours and five minutes of slow-motion footage, and then he showed it for the same timeframe. That idea of time that could be real time, was a revelation. As a consequence, if you made a film that long, it created the visitor, instead of the audience: it is too long to sit there. People came and went. That’s ofcourse what we do with installations every day. Creating structures that allow people to come and go.

What made you move to New York in 1973?

Practically all the artists I was interested in, seemed to be in New York. I was very keen to get there. It included people like Whitman, Yvonne Rainer and Simone Forti. Conceptualists like Sol Lewitt and very importantly, John Cage. I was also living with a painter in London, Carolee Schneemann, and she was feeling like she wanted to return to New York, so we basically moved together in ’73.

The energy of the city kept you there?

Yes, I was meeting the people I was interested in, I was making work. It suited me.

At 30 years of age, you questioned your career path, and began editing art books. Was this more of a practical choice to fall back on? And now, why did you

Yes, I did it for 20 years. I built up a studio. I was mostly editing and designing art books, and catalogues. After doing that for 20 years, a lot of things had changed in the world. For one thing, galleries and museums had begun to show moving image work, video work became a thing. So that had changed. It was an important change, because I couldn’t have possibly had a gallery that could have supported my work back in the 70s. The other thing is, and most important of all, was the invention of the haze machine, which enabled the problem of visibility to go away.

There was also a personal feeling, I just had to get back into it again. I stepped away from the graphic design studio quite quickly once I had made the decision. Somebody said I am the only artist that has early work and late work, but no middle period!

Based in New York, is the light there quite different to London light? It’s interesting to see what your eyes see…

I can report the lights are very different in London and New York. New York is far further south – the light is very hard and sharp. By contrast, the light in England is quite pearlescent and misty. They’re very, very different. Also the sun slants at different angles, it’s much higher in New York and it’s lower and more slanting in England.